When Rebecca Cope was in middle school, she attended Cornwallis Junior High along with her sisters. As a Mi’kmaq woman whose grandmother survived Shubenacadie Residential School, Cope knew even back then how disrespectful the name was.

“Were the only Mi’kmaq students at that school the whole time we attended it,” she says. “We were very aware of the history and our history, and we were also very aware of what type of system we were in.”

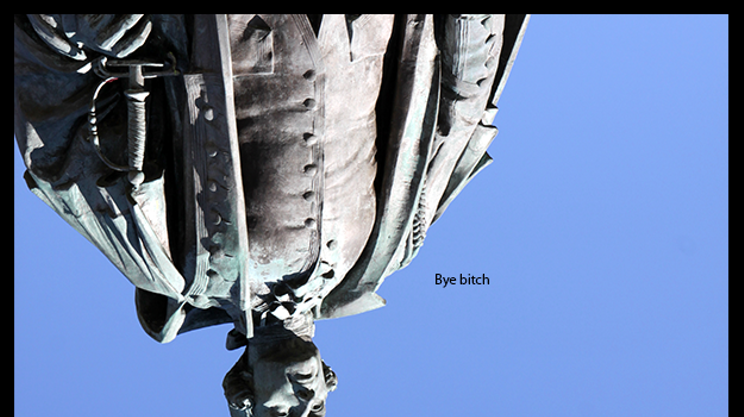

When she was downtown hanging out with friends, Cope often had to walk by Cornwallis Park and the statue of its namesake. She’d often think of the first time her grandmother arrived in K’jipuktuk after leaving residential school. “When my grandmother arrived here to the city, she got off the train and walked out of the train station—that statue of Cornwallis would have been the first thing that she saw,” Cope says. “They see this statue that tells them essentially what type of environment they just landed in.”

Cope says she knows other Indigenous people felt the shadow of Edward Cornwallis’s statue while growing up in the city. “It wasn't just me, but I know a lot of Indigenous people felt that same type of way,” Cope says. “Every time they saw that statue, every time we passed by, we would feel that energy.”

At the time, Cope told her friends that one day she wanted to see the statue come down. “I was probably 15 or 16 years old and we would walk by that statue. I swore up and down, I said ‘I'm gonna remove that before I die, that that is going to not be there.’”

And years later, that goal has finally been accomplished. “When it finally did come down, several of my friends messaged me, and they were like ‘Oh my god, you did it!” she tells The Coast in a phone call.

O

n June 21, 2021, the same day as National Indigenous People’s Day, Cornwallis Park officially became Peace and Friendship Park. That was almost four years since the statue came down, something that Cope and other Mi’kmaq women were heavily involved in. The first protest at the statue was on Canada Day in 2017.

“That year, Canada was celebrating its 150 anniversary, and it was pissing us all off,” says Cope. “We wanted to do something for our community who was actually mourning on that day, we're not celebrating anything, we're mourning all of the lives that were lost as a result of colonization, since contact.”

When elder and residential school survivor Grizzly Mamma wanted to cut her hair while praying for residential school victims, missing and murdered Indigenous women, the Highway of Tears victims and more, Cope was among the crowd of about 30 community members who gathered. “She wanted to cut her hair. Because in our culture we cut our hair as a sign of mourning,” Cope says. “She wanted to do that at the Cornwallis statue on Canada Day for her own healing.”

But in an event that made national news, Cope and Grizzly Mamma were interrupted by homegrown terrorist group the Proud Boys. “While we're praying to all of our ancestors, we hear in the distance this group and they are singing ‘God Save the Queen,’” Cope says. “And they're intoxicated, and they come up with their flags. It was the Proud Boys.”

The group confronted the Proud Boys for their interruption, and with the exchange caught on camera and right wing darling Gavin McInnes inserting himself into the situation, all eyes were on Mi’kma’ki.

After that, the fight to remove the statue of Edward Cornwallis became a popular topic at Halifax Regional Council, with several councillors voicing their hot takes or taking problematic stances. Cope and other Indigenous women anonymously plastered posters around the city, saying a protest to take down the statue would be held on July 15, 2017.

“We posted these posters all over, but didn't have much information,” she says. There wasn’t a plan in place, but Cope says the excitement alone made the city feel alive, and like real change was happening because of their efforts.

“A big part of it was getting the people going and making them feel empowered. And this was doing that for our nation. It was just giving that statement, speaking it out loud. Not knowing how but just saying, ‘It's coming,’” says Cope. “For those two weeks, while everyone was waiting for the date to arrive, everybody was talking about it, good or bad.”

On the day of the planned protest, after a large crowd turned out carrying everything from ropes to pickaxes to remove the statue, city workers showed up to cloak the colonizer’s effigy in cloth. The crowd dispersed, but the statue remained in the park.

“A couple months go by and because the city keeps on saying that they created that task force, the city kept saying that they were choosing people to be on a committee to go over what they're going to do about the whole statue issue,” says Cope. “But it literally was not happening. It wasn't moving. There was no traction, there was never any new news to who was being on this committee or anything for months.”

Over the following months, the Cornwallis statue faded from public discourse and the committee idled. During this time, Cope says herself and other Indigenous women used the Mi’kmaq story of the crow-hop to push themselves forward.

“The crow hop is the story of a crow, with it poking and poking and tapping, tapping on a tree and being annoying,” she explains. “Making so much noise until the worm pokes out to see what's going on—and then that's when the crow gets it. So we were always coming up, always keeping the news relevant.”

This included an impromptu meeting with HRM Mayor Mike Savage on Treaty Day, October 1. Cope says she wanted to meet with him “so that he was aware of how discouraging it was for us to be celebrating another Treaty Day while that statue is still standing.”

Finally, in January 2018 council voted to move the statue to a storage facility, where it has sat indefinitely while they figure out what to do with it next.

In the four years since then, Halifax has begun the process to rename other problematic locations. The New Horizons Baptist Church has sprung from one previously named after the same colonist. And across Canada and the US, other statues have been taken down or forcibly removed by the public, including the recent removal of a statue of John A. MacDonald, Canada’s first prime minister, in Charlottetown, PEI.

Finally, the city made the decision to rename Cornwallis Park to Peace and Friendship Park—after the Peace and Friendship Treaties that were signed in 1752. For Daniel Paul, a Mi’kmaq elder and author who has also long campaigned for the renaming of the park, it’s a step in the right direction.

“Today, with the renaming of the park and a new sign installed, we are seeing steps being implemented that are needed to find genuine reconciliation,” Paul said at the unveiling.

Paul said he hopes the park lives up to its new name. “What is better than for us all to live in harmony and to accept one another in peace and friendship?”

But Cope reminds us that it’s crucial to remember that grassroots Mi’kmaq women began the initiative to remove the statue and rename the park. She says those at the centre of the renaming shouldn’t be bureaucrats or politicians.

“We make these movements, we make these things happen, but bureaucrats always take credit for the initiatives of grassroots Indigenous women,” she says. “They completely leave the women and the grandmothers councils out of our history.”

While the park’s renaming is important, Cope stresses that reconciliation and healing aren’t just talking points, but need to be followed up by real action.

“Right now, celebrating peace and friendship is just for fashion, is just lip service. It is just to make them look nice, sound like nice Canadians. Because we still have DFO, literally stealing our fishermen's traps out of the water, we're not even allowed to fish our inherent rights to a moderate livelihood,” she says. “So, there's peace and friendship, the nice kind that sounds good, that makes Canadians feel good. And then there is the actual living state of oppression.”