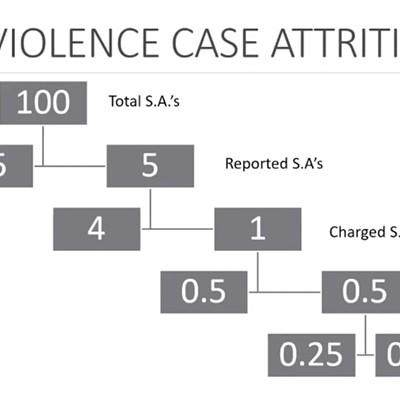

Fewer than half of sexual assault charges in Nova Scotia from 2005 to 2014 saw a conviction, a number that almost mirrors individual results about the Halifax Regional Municipality.

According to a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) report from the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre, during that decade 437 reported sexual assaults saw a charge laid. Within those charges, 31 percent saw a conviction, which could be on sexual assault or another charge. Statistics Canada notes from 2005/06 to 2014/15, there were 1,172 sexual assault court cases across Nova Scotia. Out of those, 38 percent resulted in a guilty verdict and 1.45 percent resulted in “other decisions.”

Even with Halifax being so close to the provincial statistic, neither of the numbers are surprising to Susan Wilson. A SANE program coordinator with Avalon, Wilson says the conviction rate is low because “it comes down to what the victim and the offender are saying and they are often two very different stories.”

This is something the Public Prosecution Service also

“The judge and/or jury must feel guilt has been proven beyond a reasonable doubt,” says Chris Hansen, spokesperson for the PPS.

“When you look at that, sexual assault is one of the most difficult charges to prove because it’s often in private with no witnesses and often comes down to the question of ‘he said, she said.’ And, there is often no physical or forensic evidence.”

According to Statistics Canada, 44.6 percent of charges in Nova Scotia are withdrawn or stayed, which is when the legal process is halted. This can happen before a trial even begins.

Hansen says that when a charge is laid in a case, including sexual assault, the Crown has to apply a two-part test to determine “realistic prospect of conviction” and if it’s “in the public interest to proceed.” If it doesn’t pass both parts of the test, the prosecution is halted.

According to the Public Prosecution Service,

But, this issue of conflicting stories is rooted in a much larger issue and one that relates to memory and the question of consent. This is a question that has been in the forefront following the recent acquittal of taxi driver Bassam Al-Rawi and the presiding judge’s comment that “clearly, a drunk can consent.”

Often, Wilson says, victims won’t be conscious during the assault or will be intoxicated or drugged—all of which hinders memory. The trauma of the assault can also affect how much of the event is remembered. Even if the victim knows what happened, they may not remember specific details.

“We know how trauma affects memory and a victim’s ability to recall the event; it can be altered by fear,” she says. The offender is “going to be able to recall what happened more easily and talk [their] way around it.”

This can contribute to low conviction rates, like the ones mentioned.

While some victims may avoid court altogether by choosing another method, like just having a medical examination or restorative justice, Wilson says the sexual assault case process as a whole is in need of improvements.

“[To] see justice done is to be able to respond, as service providers, in the best way possible by using a trauma informed approach…not allowing that victim blaming to happen and being able to believe and support victims. I think that is justice,” says Wilson. “It’s an injustice when we don’t know that and trying to treat victims without knowing the dynamics around sexual assault and sexualized violence.”

Wilson adds that the numbers from Avalon’s report and Statistics Canada don’t reflect the entire reality of sexual assault, as there

“It’s absolutely a deterrent for people,” says Wilson. “It absolutely does affect reporting rates and that’s not going to change until we stop victim blaming and have more support systems in place.”

Steps have been made to improve these supports. This includes the province saying in early March that they would hire two prosecutors who

“I think that’s a good start, but I would like to start seeing