One of the newest members of the Canadian Senate says a criminal case in Nova Scotia perfectly demonstrates what’s wrong with the justice system—even though the process has been fair.

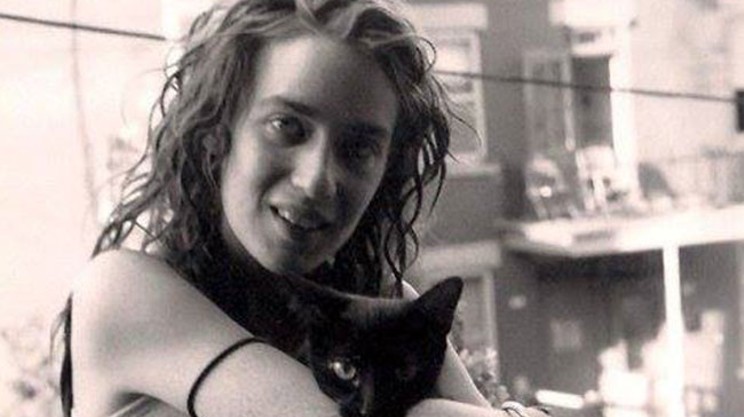

Senator Kim Pate is talking about the release of Christopher Calvin Garnier from jail for a second time. The 29-year-old is charged

Garnier is set to go to trial next fall but

Senator Pate says from everything she’s heard, the decision to release Garnier is legally sound. But that’s not the problem.

“Why isn’t every accused able to access that defence?” Pate asks.

Garnier achieved his release with the help of defence attorney Joel Pink, one of the most high-profile and expensive criminal lawyers in the Maritimes.

“Our jails aren’t full of wealthy white people,” Pate points out.

Statistics Canada reports that “over the last decade, the remand population (in adult correctional facilities) has consistently exceeded the sentenced population,” estimating about 57 percent of people in jail are on remand. Nova Scotia’s remand population is the highest in the country, nearing 70 percent.

“In some

Or, put simply: “If you’re poor, you’re more like to be charged.”

Specifically, says the senator, “If you’re a poor, racialized woman, the chances of you being held awaiting trial are much higher.”

This is a complex issue, and it isn’t new to Pate. Before she was appointed to the Senate, she spent 35 years working in and around Canada’s legal and penal systems as an advocate.

But for

“If you don’t have a stable place to live, an income, the chances of you being held in custody exponentially increase,” Pate explains. “Once you’re

The senator says she has worked with people across the justice system, from lawyers to police, who are trying to protect the most vulnerable from unfair treatment.

But she says it’s an enormous problem that must be addressed at all levels of community, government and authority.

Still, Pate points to one specific dilemma that could be changed overnight.

“All the cuts to social assistance over the years,” Pate says. “There’s no way you can survive on the rates that are provided right now.”

Poverty can directly lead to criminality, says Pate. And

Meanwhile, Garnier is due back in court in August to face charges of breaching his bail conditions, the subject of a hearing that took place last week. The murder trial is set for November.