A decade after it was originally approved and six years after its development agreement expired, the Twisted Sisters project could be shambling back to life—unless council can kill it first.

Next week, Halifax South Downtown councillor Waye Mason will be asking for a staff report on discharging the development agreement between HRM and United Gulf Developments for the former Texpark site on Hollis Street.

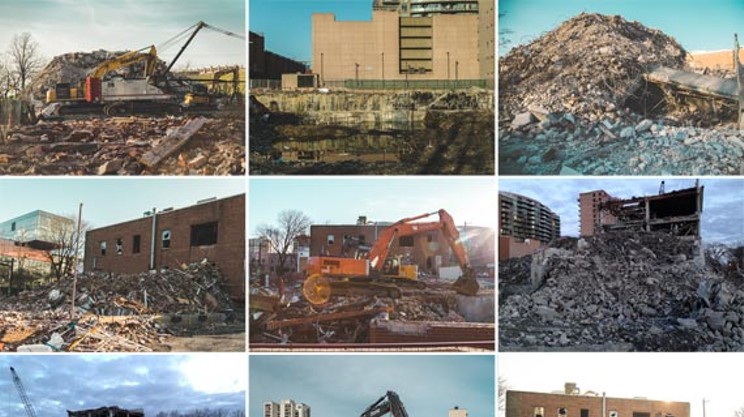

A discharge would be the final nail in the coffin for the decade-old agreement and the downtown’s most prominent development cavity. The empty Texpark lot, bordered by Hollis, Sackville and Granville Streets, has been mostly barren since it was purchased by United Gulf 12 years ago.

In 2006, council approved an agreement for United Gulf to build two 27-storey towers on a shared base. Dubbed the Twisted Sisters, the project was worth an estimated $150 million. But it was never built.

The original development agreement expired in 2010, but due to the odd nature of that document the project isn’t actually dead. Call it undead.

“It currently sits in limbo,” says HRM spokesperson Brendan Elliott. “It’s not something that died because it expired.”

Spooky, right?

Council has to either explicitly vote to kill the agreement (which is what Mason wants) or vote to bring it back to life. Until either happens, Texpark remains empty and the wraithlike Twisted Sisters continues to haunt the downtown.

The project was approved by council before HRM by Design came into effect in 2009, which means the development was able to exceed the area’s 66-metre height restriction. A discharge would keep the land in United Gulf’s hands, but eliminate the extra height allowance for any future proposals. It could also mean an end to any income United Gulf earns from the monthly parking rentals that are authorized under the original agreement.

“I think there’s an appetite to just close this off and bring it in compliance with the plan,” says Mason. “It’s unlikely council would consider letting [United Gulf] build [the Twisted Sisters] because it’s expired. But if it’s expunged, there’s no chance of that. He’d have to start from square one completely.”

“He” being United Gulf president Navid Saberi, who says he’ll be asking for an extension on the undead Texpark agreement in anticipation of a new dual-towered proposal that’s almost ready to be brought to council.

“We are doing a lot of analysis on this site, and we’re getting very close to submitting our plan to the city,” Saberi says.

If approved, it will be United Gulf’s second extension and third proposal for the property since the original development agreement came into being a decade ago.

Texpark gets its name from the Texaco gas station that sat on the site, underneath a city-owned parking garage. The structure was built in the ‘60s—after the city expropriated private homes and resettled some of those residents in the public housing at Mulgrave Park. The only development on the site since is a small five-storey office building in the south-east corner. The garage was finally torn down in 2004 and the property put up for sale.

A prominent vacant space languishing in the centre of the downtown, Texpark is the “epitome of Halifax’s ‘missing teeth,’” as The Coast’s Tim Bousquet called it in 2013:

“An otherwise prime development lot that sits empty, without buildings or even landscaping...Texpark is a blight on downtown, an embarrassment.”

tweet this

Mason actually isn’t the first city councillor to try and unshackle Halifax by discharging the Texpark agreement. Dawn Sloane attempted to do just that in 2011, when the agreement was already well past its four-year expiry date.

United Gulf’s representatives at the time argued that a new design was coming in a “matter of weeks,” and asked council for an extension. The matter was deferred, pending a staff report and to give the developer time to present its new plans for the site.

Those designs turned out to be Skye Halifax: two 48-storey apartment buildings that were more than double the Downtown Plan’s height restrictions. After some significant public criticism, HRM’s newly-elected council finally exorcised that proposal in November, 2012. In the process, plans to discharge the original development agreement seemingly faded away.

A year later Mason told The Coast the city was looking into a little-known buyback agreement to purchase the land back from United Gulf and possibly flip it to another developer.

Those plans didn’t work out, either. Mason says the buyback agreement was so flimsy that it would be nothing but a crapshoot in the courts.

“We might win. We might not,” he says, “but probably not, and it would be another big, long court case.”

He points out that the buyback agreement for the expansion of Bayers Lake was 22 pages long. Texpark’s buyback agreement, for comparison, is only four. Mason calls that legal oversight “kind of horrifying.” The municipality seems to agree.

“My understanding is development agreements today are not the way that one was created,” says Brendan Elliott about Texpark’s vaguely-written contract.

In any case, Mason wants to move on.

“He’s had his chance. It’s expired,” Mason says, about Saberi. “I don’t imagine he’ll be happy, but that’s not really a concern.”

Actually, Saberi says he’s quite happy right now.

“I’m in a positive mode,” says the developer. “There’s a lot of construction going on and things in Halifax right now, so I’m looking at it in a positive sense.”

If council does vote to discharge, Saberi says he’ll just bring forward another proposal.

“If that’s what they do, then we’ll probably design something else,” he says. “You have to do what’s best for the city. We think this is the best design for that area.”