Pastor Rhonda Britton is striving to perfect a balancing act. At one end of the spectrum is a chorus of voices—enraged and betrayed by proven, repeated discrimination. On the other end are the promises and actions of those in the seats of power.

Britton must be the bridge between both.

It's exactly what she was trying to do last

But this year's joint service came just days after an emotionally charged meeting at the Halifax North Memorial Public Library on racial profiling, in which chief Jean-Michel Blais asked an audience member: “What do you mean by

“There is a sense by some people, that it's almost a betrayal,” Britton explains, “to welcome him in.”

It's a wintry March afternoon. Britton is eating a late lunch of broccoli soup at a Tim Hortons. She wears tall boots, a colourful scarf and a puffy turquoise Jacksonville Jaguars coat. Her floral print glasses frame big, sharp, bright eyes. It's stopped snowing, for the moment, but the sky seems to warn more is coming. It's been a couple of weeks since the annual police service.

“He and I talk,” Britton says of chief Blais. Despite her disappointment in his comments, she says the way forward must be together, which is at the heart of the annual service. To “try to get people to see each other as human beings,” she says, without ambiguity.

Maintaining an open, committed and engaged relationship with the top brass at the police station, and the mayor's office at city

The question of how to address violence in the Black community isn't a new one. Nor is the question of how to address discrimination against the Black community. Often unspoken are the fundamental unmet needs, now generational—the toxic remnants of racism dating back before Africville that still haunt the present day.

These interconnected wounds predate pastor Britton's arrival in Nova Scotia. But in her 10 years leading the congregation at the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, she says the atmosphere of unsettlement in the community has only gotten worse.

“It's just an uphill battle,” she says, reciting the “discouraging” list of suggestions she's brought to the police and city council over the last decade that

“Sometimes you wanna give in,” she admits.

Take St. Pat's Alexandra as a case study. The brick elementary school on Maitland Street was sold in 2016 by HRM to Jono Developments for $3.6 million. The obvious solution, Britton feels, would have been to keep the building and leave it open and accessible as a leading-edge community centre. Even if that wasn't possible, she can't understand why the city didn't offer to share some of the profits to directly help out neighbourhood programs.

“You hear them saying ‘Oh yes, we need to do something about this,’” she says, but when it comes to tackling the parallel issues of violence and discrimination, the response she keeps getting from the city year after year is always the same: There's never enough money.

“You've got [the municipal government] spending $25 million on the Halifax Convention Centre,” she says, “but you can't spend $2 or $3 million to help one of the most vibrant parts of the city?”

There's another question Britton finds herself repeating: “How much is a life worth? What is the price tag on a life?”

Britton was born in balmy Jacksonville, Florida, the self-proclaimed Bold New City of the South. Later, growing up in New Jersey, she was a devout church-goer. Britton says she was first “called” at age 15. But she didn't know what it meant.

“I didn't have any experience in...discerning that call,” she says, letting a little breathing room in between her words. And then, having found her answer, she lays it out plainly.

“I grew up Baptist. There were no female ministers. So I just figured I was misunderstanding something.”

But the moment itself was a powerful one. She was praying one day, sitting on her front porch. She asked god, “Ok. Show me. What is it that you would have me do?”

Her answer came in an image.

“I had a vision of myself...speaking to this huge crowd of people.” Her face scrunches up. “What is that about?!” she recalls thinking at the time. She laughs about the old memory, loud and clear. It fills the space around her.

“Pastor Britton?” a woman approaches, unsure of herself and then chuckling in recognition. “I saw you in the line...but didn't know it was you!”

It's a warm reunion as Britton and the woman reach over her soup for a hug. “Are we really changing the name of our church?” she asks with uncertainty in her voice.

“Yeah,” Britton replies, matter-of-factly.

“That's what I heard,” the woman repeats, sounding unconvinced, “What are you calling it?”

“Don't know yet,” Britton answers. “Gotta have a contest!”

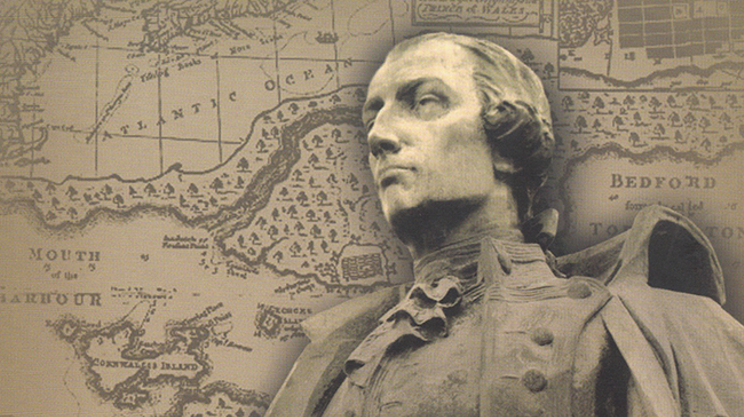

The church, as the street it rests on, is named for Edward Cornwallis, who was governor general of Nova Scotia in 1749. Though he's known as the Founder of Halifax in history books, Cornwallis is infamous for tendering the scalps of Mi'kmaq men, women and children.

Cornwallis was “an oppressor of our First Nations brothers and sisters,” Britton told reporters last month. “We don't know what the name of the church is

The name change made news across the country. Right on cue came the blowback. In her role as leader of the church, pastor Britton doesn't just hear about racial intolerance—she experiences it herself. Last week, via Twitter, Britton made public an example of the hatred Black people in Nova Scotia are still subject

“I am getting sick and tired of anti-white racists like you and Chief Daniel Paul spouting your anti-white hatred,” writes a Christopher Bazinet. “You both need to get over your whining and

Britton's response?

“#PrayingForThisPoorSoul”

Britton's path to spiritual work is woven with detours. She was first asked to address the congregation as a young woman, earning praise“I grew up Baptist. There were no female ministers. So I just figured I was misunderstanding something.”

tweet this

“You have a call on your life,” he urged her.

The same message kept chasing her over the years, through different voices but with growing intensity. A man Britton calls her “spiritual father” once reproached her. “You are running from your call,” he said.

“I would just brush him off,” Britton says with a laugh. She remembers one time heading home, back to Jersey, after attending a religious retreat in Brooklyn. Driving through Staten Island in her Toyota, it struck her: What would it mean? What would it look like to devote her life to the church? By the time she got to the Verrazano Bridge, her old refrain was back with full force.

“Nahhhhh!” she imitates herself, shaking her head comedically. Another burst of laughter fills the corners of the room.

The man who convinced Britton to leave the United States and move to Nova Scotia is himself from New Glasgow. Peter Paris was one of Britton's professors when she finally heeded the call and began her studies, at the prestigious Princeton Theological Seminary.

At a Christmas party for Princeton's Black Students Association, hosted in his own home, Paris asked Britton what she intended to do after graduation. Britton already had many offers, including leading roles in churches in Virginia, and Johannesburg, South Africa.

“She responded, laughingly, that she was hoping that the Lord would call her to a church in a warm climate,” says Paris. “I responded by saying that ‘The Lord may call you to serve in a church in a cold climate.’”

At the time it was merely a joke, but after her mother dreamt of Britton preaching in Canada, she became curious. What exactly did Paris mean when he'd said “cold climate?”

“I vividly recall thinking about my home church,” says Paris. Second Baptist Church in New Glasgow wasn't just Paris' home church; it was home. His own family still worshipped there, and his sister served as the parish secretary.

Paris said he believed Britton belonged there.

Not long after the conversation, another one of Britton's professors stopped her in the mailroom. “I hear Peter's trying to get you to pastor his people,” he said.

“Oh I don't think so,” Britton replied, still uncertain about making the move.

“Let me tell you something,” he said to her. “Peter's been at this school for over 20 years. That church has periodically needed a pastor and there has never been any student, or any professor, or anybody else that he's asked...even just to preach for a Sunday.

“He is entrusting his family to you. You have to think about that.”

Britton was speechless.

“You're a praying woman,” he replied. “You'll pray about it.”

Eventually, Second Baptist Church did invite Britton to become its pastor. And to Paris' delight, she accepted. Britton was the ideal choice, he says, because she's “a person of unquestionable moral integrity.”

And so, Jacksonville-born, Jersey-bred Rhonda Britton found herself in Nova Scotia. A few years later she was first asked to preach in a historically Black church in the north end of Halifax. But she didn't accept. Not right away.

“I said, I don't feel it's time for me to leave...”

The call from Cornwallis Street Baptist Church didn't go away. Two years later, the position was still vacant.

“Waiting for me,” says Britton. “That's what I like to say. It was waiting for me.”

It's the first Sunday morning in April. Tiny snowflakes are blustering aimlessly, melting as they hit the wet ground. Inside the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church, the lights are up bright, the sound of laughter punches through the air and the faint smell of aged wood mixes with drifting perfume. The ushers embrace each

Long winter overcoats of poppy red and creamy white are carefully removed as people arrive, cloche hats and gloves, in vibrant hues, dotting the crowd. Canes lean against the pews here and there, as parishioners stoop low to greet their bearers.

A woman starts playing cheerful revival chords on an upright piano while a man sitting next to her joins in on electric bass. A line of singers

In the middle of it

As the song changes, everyone in the church rises to their feet in unison. Together, they begin to sing the words “We're standing on holy ground.”

Some lift their arms. Bursts of “Yes!” and “Amen!” chime in with spontaneous applause from across the room. The voices are strong, clear, full of conviction. They all blend together as Britton leads, with arms outstretched. It's as if she is lit from within, beaming with grounded rapture.

Everyone is singing.

“This is healing ground.”

“We're standing on healing ground.”

“I always say how freaky it is: The church was there before Canada was a confederation.”

tweet this

Britton isn't the only pastor born in America to occupy the pulpit on Cornwallis Street. The first voice leading congregations belonged to another American, reverend Richard Preston. The son of a slave, Preston travelled to Nova Scotia from

In late April, the stately yet simple building on Cornwallis Street will celebrate a monumental anniversary by turning 185 years old. It has endured nearly two centuries, the blast of the Halifax Explosion (and in the following days, sheltered those displaced by it) and pre-dates the very country it's a part of.

“I always say how freaky it is: The church was there before Canada was a confederation,” says Britton.

There are lifelong members of the congregation who are half that age. “In their 90s,” she marvels. “One woman, coming up on 100.” Recently, the church celebrated a group who have each been singing in the choir for 50 years.

“It's tremendous, actually,” Britton says with a smile.

Bridging that historic past to the trials and triumphs of today is someone whose first career choice was in business analytics, of all things.

Before she found her way to the pulpit, Britton worked for Johnson & Johnson in New York as an information engineer. She was in constant contact with a multitude of departments trying to find out what data was needed, why it's needed and how it was to be used.

“To try to get into their hands what they need to do their work,” she says.

Abandoning an ascending career in corporate tech in an iconic city to take on a small historic church in a faraway province she'd never even heard of might sound like an incongruous departure. But maybe it wasn't. Maybe Britton was heeding her

Years before she attended Princeton, she hung in her New York City office a picture of a woman weaving baskets. When people asked her about it, she'd tell them that's just what she did.

“I'm a basket weaver. I'm gonna put it all together.”

Maggie Rahr is a tutor in the journalism program at King's College. She won an Atlantic Journalism Award for her CBC Radio documentary about LOVE Halifax.