T he crowd of friends knocking around pool balls and chalking cue sticks don't know who Morgan Davis is. Their laughter bubbles and expands, filling the bar on an otherwise quiet night. The sound threatens to drown out Davis and his modest Ampro amp after he flicks through his mental songbook and begins playing on Bearly's corner stage.

They don't know he's a staple here in Halifax at the House of Blues & Ribs, playing an encyclopedic set of blues every Monday night.

They don't know how he was part of the bedrock of Toronto's blues scene, backing legends while also building a repertoire of bulletproof originals, before moving to Nova Scotia after a raucous three-night stand at The Middle Deck.

They don't know how his singing voice swells and creaks like an old house in such a way that Howlin' Wolf's own guitarist thought Davis was the ideal stand-in for the legendary musician, or how he played the solo from Sleepy John Estes' "Goin' to Brownsville" so well that the original soloist himself—Yank Rachell—waited, stage side, to introduce himself to Davis.

Someone sinks a ball into the corner pocket. They cheer.

Meanwhile, Davis settles on the perfect song—Dorothy Love Coates's "Ninety-Nine and a Half Won't Do"—and, all of a sudden, the crack of cue-on-ball is silenced. By the song's last notes, the only noise coming from the table is a collective exhale and applause.

Twenty-twenty marks Davis' 50th year as a professional musician.

The story of his musical beginnings is well-worn, having been told at least a dozen times, probably first in 1986 to the Toronto Star: At age 16, while growing up an outsider in what he calls the "lily-white," Beach-Boys-cosplay of 1960s Downey, California, Davis broke his leg. The recovery process saw him cooped up in bed, learning guitar. A love for blues planted during his early childhood in Detroit—"I was hearing Ike and Tina Turner, Jimmy Reed, Fats Domino; all these formative R&B blues music," he says—returned. It's been blooming for Davis ever since.

"It's always been grown-up music that tells the truth. Anything I've gotta say, I can say with the blues," Davis says.

"It kind of creeps up on you, y'know? You do 20, you do 30, you do 40 and I mean, half a century of doing this is just—it's quite remarkable. It's a long-winded answer, because I mean, is there a progression involved here? Are you in the same spot you were?" he says. "Have you advanced? I guess the main thing is, I go through the 50 years and I keep making new fans. As long as I keep making new fans, it's worth goin' out there and doin' it."

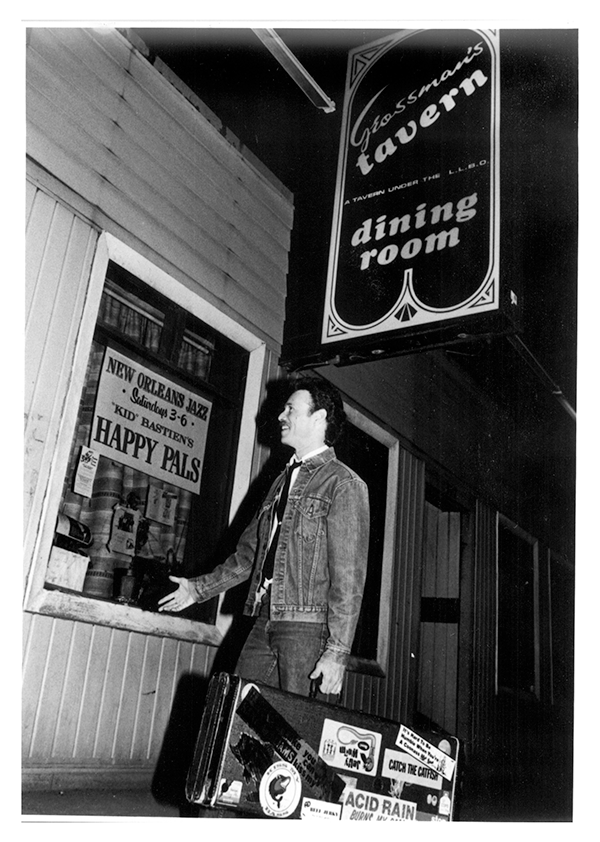

It's been several weeks and one extensive European tour since that night at Bearly's. Davis sits at his kitchen table. Around him are photo albums, each with a number of chronology affixed to its padded front in a teeny white sticker with blue pen. Between the plastic-coated pages, the story of a career, of a life, of a scene, of a genre is told in snapshots and newspaper clippings. He's giving a tour of five decades as he leafs through them.

Davis started in 1970 in a small, Buffalo Springfield-looking act called The Rhythm Rockets (the band's black-and-white promo photo opens scrapbook one), "where I learned to be in a band—it was a great education," he says. Next, he was fronting the intentionally ambiguous, acid-rock-named Knights of the Mystic Sea ("we'd say we played dance music," Davis begins, arching his eyebrows to remind you that yes, you can dance to the blues. "That's how I survived the disco years.").

His first big gig was in the upstairs room at the legendary Toronto live music dive El Mocambo in 1974—the same year Nixon resigned, Eric Clapton covered Bob Marley's hit "I Shot The Sheriff," and The Rolling Stones released It's Only Rock 'n' Roll. (Three years later, the Stones would play the same stage as part of a surprise gig, with Margaret Trudeau wylin' in the front row.)

Davis kicked around LA during the city's early punk days, playing blues in a garage with boogie-woogie pianist Gene Taylor for three months. He left minutes before Taylor's rockabilly-blues hybrid The Blasters gained instant cult status for its souped-up spin on rock 'n' roll.

In 1978, despite Saturday Night Fever and the Bee Gees' burgeoning world domination, he formed Morgan Davis and The Catfish. That lineup saw Davis secure permanent resident status for a post-Blasters Gene Taylor—and a regular gig while becoming a staple in Toronto's blues-revival scene.

A few years later, Davis would strike forth on a solo career, but not before backing up blues legends (and personal heroes) like Hubert Sumlin and Snooky Pryor at clubs that also hosted the likes of Billy Idol and The Ramones.

Davis promised back at Bearly's that he'd kept a record of his entire career, but you'd never have dreamt of an archive this exhaustive. Every drop of ink about him—from a curiously sensationalist 1980s review of Davis' live set ("Morgan's sassy blues are laced with sexism" blares the headline. "What the fuck?" he says, pointing to the review the writer later admitted to fabricating) to simple listings like "Morgan Davis with his brand-new band. No cover Mon-Wed"—are wedged between the albums' pages.

"I was 27 when I jammed with Sunnyland Slim, and he was in his 60s. I thought he was ancient," Davis, who'll be turning 72 this year, recalls with a chuckle, pointing to a snapshot. The pianist, who helped Muddy Waters hone his sound and played alongside the likes of Howlin' Wolf, was in town with an open stage. "I sat in with him on Sunday night and he was like, 'You gotta sit in with me all week.'" Davis couldn't wait to tell the Rhythm Rockets they'd have to field a few gigs without him as he jammed with Slim instead.

Davis says weeklong sits like that were the number one thing that built his career—and that their disappearance is the biggest change he's witnessed in the past 50 years: "When I first started playing, all the gigs were six-nighter—you set up on Monday and played till Saturday, usually with a Saturday matinee. That is a thing of the past and that's really impactful on younger musicians, I think. For example, my daughter is 30 years old and she's in punk music and they play so seldom—they play once, twice, three times a month maybe."

Similar stories like the one with Slim are unfurled as pages flip and the timeline lurches forward. Davis once opened for Stax Records star Albert King, the blues guitarist who inspired the likes of Stevie Ray Vaughan and toured with The Doors: "He played upside-down and backwards. You like Stevie Ray? He learned every Albert King riff, y'know."

Then there was the week at Toronto's Pine Tree Tavern where Davis backed the legendary Hubert Sumlin, lead guitarist for genre giant Howlin' Wolf (y'know, the guy who recorded one of blues' biggest hits, "Smokestack Lightinin"). The favourite guitarist of Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix, Sumlin re-emerged from a sort of semi-retirement at Davis' request, papers of the day reported. "Well, we just drove down to Detroit a couple times to calm his nerves and tell him we all knew the Wolf's work is all," Davis says.

Midway through photo album six—or December of 1980, the same month John Lennon was killed—a newspaper clipping of a concert review is pasted amidst other ephemera. In several sunny column inches, a Toronto Sun journalist captures Davis' magic as he recounts the night:

"In a rare turn of events Monday night at the El Mocambo, the no-cover downstairs show of Morgan Davis and Colin Linden outshone British R&B stars The Inmates, featured in the pricey upstairs room. Downstairs, Morgan Davis and his pals were a good, cheap high, drawing from the same R&B bag—but the all-star local quintet exuded a well-defined personal style The Inmates lacked."

"Is that the one where they misattribute me as being Keith Richards' favourite guitar player?" Davis asks, tapping his pipe into a glass ashtray. (It isn't. That was in book five, when Davis played with Richards' actual favourite guitar player, Hubert Sumlin.)

"H ere's around the point they started to call me a veteran," he says, pausing for emphasis as his eyes roll skyward. It's deep into photo album seven—as in, the mid-1980s, when MTV ruled supreme and few stars shone brighter than Michael Jackson—by which point Davis has found his stride as a solo act.

"What makes me uncomfortable is when I get introduced as a legend," Davis says. "I know who the legends are. I'm just a student of this music. Call me a veteran? Great. Just don't call me a fuckin' legend. I'm white. I had an easy time. The legends couldn't find a motel room or a place to eat—those were the guys who really loved what they were doin'. I got an easy road."

It's an on-brand statement for a guy with a vintage peace sign pinned to his lapel, a guy who came to Toronto in the first place as a Vietnam draft dodger. (When asked why he didn't return to California to pursue music longer term he shrugs: "All my friends were gone or dead from the war.")

It's also decidedly the right sort of thing for a musician, particularly a white one, to say in 2020. But Davis—who drops Naomi Klein into conversation often and has an anti-Trump poster taped to his fridge—means it.

This is clear, not only in his aversion to saying what he thinks people want to hear ("Y'know, this age of political correctness: I speak my mind onstage and offstage—I think we've lost our sense of humour in a lot of ways," he says, sounding his age for the first and only time in a four-hour conversation) but more importantly, in his live shows.

Back onstage at Bearly's, Davis carves out a space between entertainer and professor, improvising a fact-and-detail rich intro into every cover he plays. Watching him is a history lesson of not only blues music but of 20th-century America: He sketches biographies of pioneering musicians as he tunes his guitar and throws away lines like, "I'm gonna play a song by Mose Allison written in 1962—but it coulda been written last week: 'I don't worry about a thing/'cause I know nothin' is gonna be alright.'"

Davis' pre-show routine is well-worn after 50 years: Knock back a large double-double, set up a velvet-lined guitar case for donations (the accompanying sign says "support your local bluesman" in navy, hand-drawn block letters), check the amp levels and finally, retreat to the car to get into a performing headspace—and to have a quick smoke.

When asked his favourite performance, he shakes his head: "My favourite place to play could be here tonight—it just depends on the makeup of the people. People think it's about how you are on your best night, but it's not. It's how you are on your worst night. Someone who stumbles through on that night, that's who you are. So you gotta get up to that level of smokin' that your worst is still up here," he says, hand raised almost to the car's sun visor.

Then, toke break finished, "It's showtime," he says with an excited clap as he exits the car.

You'd almost think a few hundred were awaiting him inside Bearly's instead of about 30.

Davis says his recording output includes 10 CDs and two LPs of his own. He weaves originals through his set like a silk ribbon being pulled taut: They gleam subtly, never feeling out of place amidst classics. A sense of irreverence, of start-stop, foot-stomp, big-drums-and-bigger-guitar unspools from his 1982 debut I'm Ready To Play through to 2017's Home Away From Home.

"Blues is celebration music, not downer music," Davis told an Ottawa Citizen reporter in 1981. The case is proven across his own catalogue, with tracks like 2014's "I Got My Own" winking amidst minimalist lyrics:

"Sometimes you got to gamble/Sometimes you play it safe/Many times you got to scramble/Othertimes you gotta wait."

This sense of fun—coupled with the unique affectation Davis' guitar takes on as it warbles and pops—is what makes him so great. Davis' love of the music, and his unique interpretations of it, means a cover is never a simple note-for-note copy: He knows he can't be Son House when playing "Empire State Express," so he spins the classic blues tune in a new direction.

And while it'd be easy to say that the blues chose him, that he never could have done (or played) anything else, playing the blues meant swimming upstream, away from trends of the day—and by extension, broader success: "Blues guys don't get rich and famous," Davis correctly forecast in a late-'80s clipping from the Toronto Star. When it came time to release his first solo record, he formed a label—named, in equal parts a middle finger and a wink, Bullhead Records—once it became clear no established label would take a chance on him (this changed by 1989, when, amidst the birth of grunge and the release of Nirvana's debut, he released a self-titled LP with the indie Stony Plain Records. He returned to the DIY route for every subsequent album).

Davis has kept every rejection letter from that era dotted across his scrapbooks, an even record of wins and losses on each two-page spread.

It's hard not to wonder if the record execs would've changed their minds if they heard the magic and myth-weaving at work in Davis' live sets. If, then, the ledger of shows he keeps—a calendar dark with Xs to mark the full warmer months, dwindling during the dead of winter—would instead be dotted with arenas, or at least ballroom venues.

But Davis doesn't indulge in what-ifs. Across five decades, he's never had time for a narrative of undiscovered gem to be thrust upon him. "You can't let yourself get bitter. I consider myself real lucky and real successful at what I do: I manage to make my whole living playing music and I've always been able to play the music I love. If I had to play music I didn't like, I'd just as soon drive a cab," Davis told NOW magazine in 1988—the same year hip hop hit its stride with everyone from N.W.A. to Slick Rick to Jazzy Jeff and The Fresh Prince dropping records.

Instead, he's been too busy touring and recording and playing gig after gig, earning attention by whatever means necessary and keeping it with his immense talent. (Once, to drum up attendance for his New Orleans-themed New Year's Eve show, he had a meal of red beans and rice as part of his show: "I made red beans and rice for 80 people for that gig...and somehow I heated 'em all up and served them and played three sets," he says. He'd repeat the same trick with jambalaya another New Year's.)

Back at Bearly's, as he drains his coffee and ambles toward the stage, Davis says: "I think, as a blues player, you have to be very respectful because every player goes to the same well and draws out inspiration. It's a very deep well. The key is to kind of find your own way of saying or using the tradition. Oh, I'm still workin' on it—I haven't arrived." He pauses, the "Support Your Local Bluesman" sign framed by his shoulder. "It's a lifelong pursuit, I don't think anybody has it down."