Running until October 10 at Neptune Theatre

Tickets at neptunetheatre.com

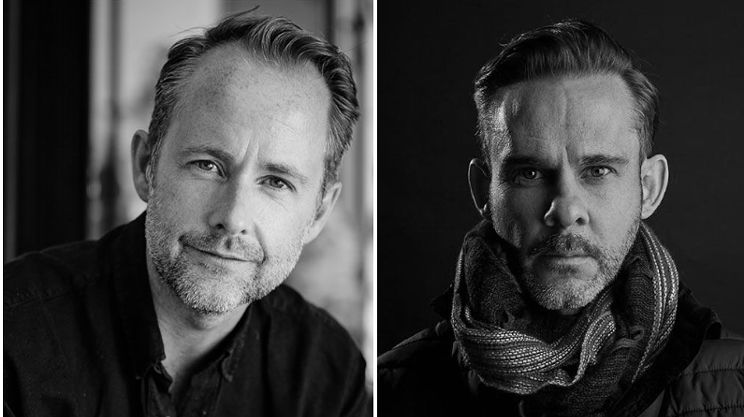

Breton Lalama began preparing for his latest role—a starring turn in Neptune’s season-opening, once-actor play Fully Committed, on until October 10—long before reopening plans meant live performance was back. It was before the theatre announced what its returning slate would look like, and even before the first casting call was drafted.

“Sam is just me,” Lalama says, sitting in the last rays of summer’s fading sun one recent afternoon. “I worked in service for like nine years. I worked at a call centre. I wore that headset. I did this thing, it's very real. And there's something to be said for being on a stage, in a theatre, as a professional actor, playing what you did to get there.”

He mightn’t have known it when he was sweeping crumbs off five-star restaurant tables or ferrying $300 cheese plates to customers, but these “Joe Jobs” (as Lalama calls them) were an early brush with the theatrics of dinner. Now, playing an overworked reservations manager at a nameless NYC hot spot over the course of one particularly hellish shift, they’re done with the dress rehearsal: They’re delivering a one-actor show for Halifax audiences to devour.

Lalama (who uses he/him and they/them pronouns) saw his acting career grow new legs while he was living in Toronto, skipping university class one day to try out for a part in a touring rendition of the classic hippie musical Hair. “I remember getting that email in my dorm room, and thinking: If I don't get this, like I don't really know how I'm going to survive—it felt like that,” they recall with a laugh. He got the part. Since then, his resume has amassed roles across stage and screen, including a supporting role in the FIN-selected film Dawn, Her Dad and The Tractor and Pleasureville at Neptune in 2019, where Lalama was the first trans person in a specified non-binary role (now, though, they identify as transmasc as well as non-binary).

“I had agents who told me that I wouldn't work if I did what I wanted to be called,” Lalama says, eyes clouding. A casting call for a non-binary role in Pleasureville made him take the trip to Halifax from Ontario, and they’ve been here ever since. “That's why you do it, because the media that we consume as people hugely influences our subconscious idea of what is possible. And we are only able to be what we know we can be, to a certain extent,” he says.

Does opening the season at Neptune as a non-cisgender person feel like a landmark, I ask them? “If we are the stories we tell ourselves—and I think we are the stories we tell ourselves—then if you see someone like me, or any other body that is not the norm on stage or in a film, then you just added a different telling to your own story. And that changes how you move through the world,” he replies, nodding.

Fully Committed was a Y2K-era off-Broadway smash, which later became an on-Broadway work starring Modern Family’s Jesse Tyler Ferguson (presumably riding the 2010s wave of restaurant-obsessed foodie culture that crested with the musical Waitress and the back-waiter novel SweetBitter—a job Lalama also worked). The script comes off a touch too vintage at points, touting a menu of now-outré molecular gastronomy and hinging on do-or-die phone calls confirming reservations: Something unfathomable in today’s text-preferring app economy. (One particularly acidic customer asks Sam why the restaurant doesn’t use the app OpenTable “like everywhere else.”) And, Sam doesn’t ask anyone’s vaccination status when slotting tables, of course. His boss, meanwhile, is more Gordon Ramsey than Anthony Bourdain, a puckered asshole whose lone joy seems to be yelling at his underlings.

“I truly do believe anyone can do this show. People keep fighting me on that. I believe it will look different for every person, but it should. Anyone can do it—you just have to be crazy enough to want to do it.” Lalama says, explaining they pull 16-hour days to play the show’s 41 characters (Sam and all the folks who phone him; one more character than Broadway did because Lalama and show director Jeremy Webb decided to up the ante). “I know that people think that's a bit extreme, but ultimately, I want to be able to go out on that stage and have fun. So it's selfish, because I work so hard so that it becomes easy, so I can have fun with you on stage.”

Over the one-act show’s 90-minute runtime, Lalama juggles the voice changes and mannerism of a booked-up restaurant with surgical precision, the type of polish that’d allow an amateur to mistake it for easy. “It's absolutely insane: 41 different characters, to carry that around in your head all the time? And you do. I’m not being them right now, but they're there,” Lalama says, tapping their forehead. A ringing phone must, at this point, be the refrain of his dreams.

As Sam’s shift progresses, he becomes an actively worse person in front of the audience’s eyes. At first, it feels like wish fulfillment, watching the character throw his lazy coworker under the bus or letting his boss deal with the ranting customer on line one. But the reason why real people don’t do these things in toxic workplaces isn’t because they lack the guts—it’s because it’s beneath them. I ask Lalama about this, and about the play’s message. Is it that empowerment and entitlement are all too often confused?

“The question that I have asked people when they say that is, well, do you think Sam got the part?” Lalama asks back, referring to the audition callback his character gets mid-shift—and believes is a sure thing. “What I think this is a story about is how we all have needs. And, what are we willing to do—how far are we willing to go—to get the thing that we want?”