At issue is the Youth Advocate Program. Started with help of a $1.9 million grant in 2008, YAP is an intensive intervention in the lives of youngsters aged nine to 14, those judged most likely to get involved with gangs at a later date.

As we explained in 2010, using the example of one child, called "File #400":

Thirty children, including File #400, are targeted in those areas. Six youth advocate workers---college students, mostly, studying social work and from the neighbourhoods or living in them---are assigned to the children and their families, one worker for five families. The worker connects the family to existing services, but also provides coaching for things many of us take for granted.A staff report for today's council meeting detail's Ungar's report, misspelling his name in the process:In File #400's case, for example, the parents were "unreliable," reads a report. "They were unable or unwilling to take responsibilities for their children's actions---it wasn't uncommon for he and his younger brother, who's around seven, to be out at two o'clock or three o'clock in the morning, on a school night. There was no structure or schedule in the home, there was role confusion between the mother and the daughter. There was role confusion between the parents, a lot of violence in the house. There were no rules of authority established between the parents and the children."

The youth advocate worker helped the parents learn basic skills—how to get children up, dressed and ready for school, making household rules, developing routines, returning stolen property and so forth. Eventually, a regular family life was established, and after nine months, "the criminal activity stopped," says the report. The boy entered into a normal childhood, the parents had newfound skills to raise their other children, the neighbourhood was at peace.

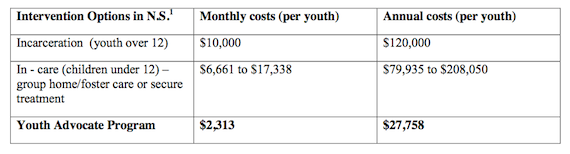

The Youth Advocacy Program is expensive—about $600,000 annually, or $20,000 per child. But that's arguably far less expensive than the future damage wrought by these worst-of-the-worst kids that don't get the attention: the policing and legal costs, the prison costs, the stolen property, the loss of a potentially productive citizen.

Unlike most government social programs, the success of the YAP is judged by an outside evaluator, Michael Ungar, a professor of social work at Dalhousie. Ungar can't give specifics until his final report comes out, but a preliminary report praises YAP. "It successfully targets who it's supposed to target, and it does it well," says Ungar. "We can't say that it works with every child, but it's clear it's making a big difference."

Dr. Michael Unger, Director of the Resilience Research Centre, Dalhousie University, is an internationally recognized researcher of at-risk youth, and was retained to evaluate the program over the four-year pilot. In March 2011, in the Final Program Evaluation Report, Dr. Unger concluded the program to be “a national model for at-risk youth”. In August of 2012, the National Crime Prevention Center confirmed the YAP to be successful, evidence based national model in preventing youth from joining gangs. A summary of the key evaluation findings include:YAP costs $550,000 a year, but the savings are quite large. The staff report includes this chart:• youth who successfully graduate from the YAP program, show an increase in school attachment and a reduction in anti-social behavior, and increase in resilience;

• there is decreased engagement in risk taking behavior, specifically substance abuse;

• there are clear reductions in impulsivity levels; attitude toward aggression, guns and violence and gangs have become less permissive;

• there is increased family relationships and family cohesion;

• partnerships have been established with over 70 different non-profit, private, and government organizations; and

• utilization of para-professionals (staff) is innovative and effective.

But beyond the monetary savings, the positive effect YAP has on human lives is incalculable. It is a good program. A great program.

City staff, however, want to muck around with the administration of the program. Why? Because a lawyer didn't like it. Explains the staff report:

YAP has traditionally been provided under the jurisdiction of Community and Recreation Services; however, during the Program review, staff from Legal Services observed that YAP’s key objectives and functions relate to “crime prevention” rather than “recreational programming”.So from the comfortable confines of a City Hall office, some random lawyer decided that running YAP out of the Rec department offended his or her sensibilities, and so council is being asked to move YAP's administration from the Rec Department to the Police Department.

Thing is, no one bothered to ask Ungar if this was a good idea or not.

The Coast called Ungar today to ask. He was completely in the dark about the suggested administrative move.

"Jesus, is that what they're going to do?" asked Ungar.

He then explained his view:

We have an amazing police force that's doing some great outreach into the communities. And the police have been very, very supportive of the Youth Advocate Program. They've been very integral to keeping the program vibrant, and supportive of it.Council is scheduled to discuss the issue some time after 1pm today.But, when we evaluated YAP, it sat very nicely where it was, because it wasn't sold to parents who had burnt out on systems as a heavy-hand in their lives. The way it was done, and the way it was positioned, it was perceived by parents of these kids as something that was not intrusive.

So, yea, if I had a vote, I definitely would not shake it up, one, because the team that has been built over at recreation has done an excellent job with it, and the perception by the parents has been that it's not child welfare, it's not corrections, and it's not IWK or mental health. It's a program that can get into the communities and get into families that have not been happy with, or have been flooded with too many services.

My perception is that it works very well under recreation, and in fact that is actually part of its appeal.

I don't want to make the police out to be the bad guys. They've been very helpful in keeping this program alive. This should not come off as they're going to screw it up or that they're evil in any way, shape or form.

It's how it's presented to the parents. You've got to think about it not from the point of view of administration, but from the point of view of the kids and families who had previous contact with the law. And this is to prevent the kids from becoming involved. The perception with these families is extremely important, and one of the big findings we had through the evaluation is that some of the perceived informality of the workers allowed the families to join with the workers, much more so than many other agencies they had gone through.

There's no good clinical reason to move it, and certainly the evidence would support the opposite: that the program's success was based on where it was positioned.