Several months ago, Anna was sexually assaulted. The man was an acquaintance in Halifax’s arts community. They had met at a party, and left together later that night. There were no warning signs about the man Anna went home with that night, and nothing to indicate his reputation for violence. But people knew.

“In the aftermath of that, when I was getting some really solid support from my pals, it was this really fascinating experience of every time I told somebody new about it the response was ‘Oh, him. I had the exact same experience.’”

Repeatedly, Anna (not her real name) heard about the man’s history of sexual assault. His character seemed to be well-documented amongst the city’s women.

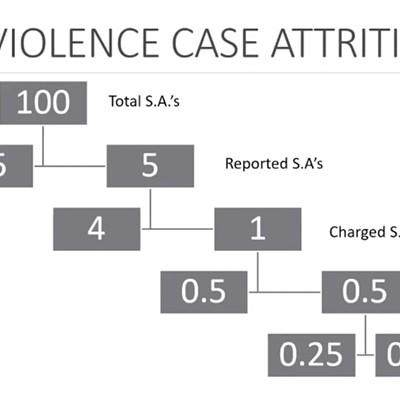

According to the YWCA, less than 10 percent of sexual assaults reported to police in Canada result in charges. Over 97 percent of sexual assaults are never reported at all. Many women turn instead to a more informal public safety system; sharing stories with friends and strangers as a warning against certain men in the community.

“I was sending a staff member to a meeting he was running. We don’t really have the ability to not work with him—he has too much power. So I told her what I knew, while also telling her I was 100 percent not allowed to tell her. I definitely do not have enough clout to call him or this organization out. It would be job suicide if I did. But regardless of our policies it was dangerous to send a female staff member to a meeting with him without telling her.”

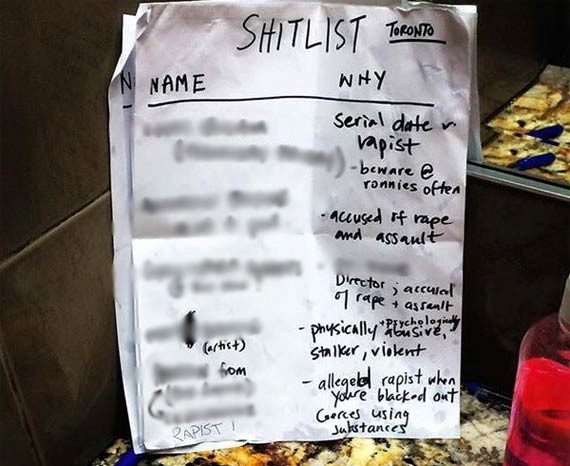

Recently an anonymous three-page “shit list” of alleged rapists in the music and arts community was posted in the women’s bathroom at an L7 show in Toronto. A marker was left by the pages for others to add names. Photographed, then shared on social media, it re-ignited a debate on where the line falls between defamation and public protection.

“We’re at this really important moment where our legal system can’t—it’s not equipped to—receive these allegations and it’s not equipped to safely receive women,” says Maggie Rahr, a freelance journalist in Halifax. “So this is kind of like this guerilla justice that’s happening in the background. Is it flawed? Yes. Is it perfect? No. But it’s there in the absence of anything else.”

Rahr saw the “shit list” pop up on a friend’s Facebook timeline, where commenters criticized it for the harm it would cause the men’s reputations. As a journalist, Rahr is well-aware of the problems with this type of public outing. The “shit list” is defamatory, and virtually impossible for the media to investigate, let alone police. That doesn’t mean it’s not true. It doesn’t mean it’s not needed.

“I think while this is an imperfect system—and a flawed system—a public list accomplishes something that no other governing body or authority can accomplish for women right now,” says Rahr.

This public “shit list” is only the most codified example of a longstanding tradition between women and within social communities. Despite the social media buzz, its origins lay not in public shaming but the extraordinary lengths women take to protect each other. The Coast asked a group of women we know if they could think of a time they had personally warned another woman about a community member’s history of sexual assault. We received dozens of replies back, and included a few throughout this article.

“You're almost trying to check the temperature of whether the person you're speaking to is open to what you're saying or not. Sometimes it's both of you walking on egg shells and then when you realize you're on the same wavelength, you kind of experience huge relief.”

Anna says she’s always been fascinated with how women develop these informal networks of safety warnings. Especially within entrenched communities like the arts, where there’s even more pressure not to accuse.

“There’s this weird underlying need to protect these asshole abusers,” she says, “but in conversations with people who’ve had similar experiences you’re just throwing these names out there.”

Recently social media and the internet have been shining light onto some of the warnings about powerful men that for many years were only whispers. It’s what led to The Casualties show in Halifax this past summer being cancelled (followed by shows in other Canadian cities). It’s what we talk about now when someone brings up Bill Cosby or Jian Ghomeshi. Regardless of criminal charges, there’s a public perception of guilt in those two cases—a change that only took decades and hundreds of personal stories to occur.

“A few months in and my friend sits me down and says, ‘Bud, you can't see him anymore. He raped my friend.’ Then she proceeded to tell me her story and I was so fucking conflicted and part of me didn't want to believe it. And that. Broke. My. Heart. I knew full fucking well how hard it is to be believed—to not be shamed or blamed—and here I was doing the same thing because I needed to rationalize my emotions.”

“I think it’s really difficult for people to believe that their friend of many years, or recent acquaintances or co-workers, could be capable of doing something like this,” says Rahr. “It’s a lot harder to say, ‘Here’s someone who was well-respected in the community, who’s fun to hang out with in a bar, who also rapes women.’ Because it makes us question our relationships, and our own sense of safety. People don’t like being set back on their heels like that.”

The uncomfortable truth is that the perpetuators of sexual assaults—to a vast degree—are our neighbours, friends, co-workers. These public conversations keep women safe from future assaults and help others feel safe enough to talk about their own experiences. It’s also one of the only ways to hold these men accountable.

“I feel like women protecting each other is so important—to the point where I feel morally responsible to share any info that could protect another woman. But I have mixed feelings about the Toronto shit list. I guess part of me really loves what it stands for and how it can truly protect other women, but another part of me feels like there could be some serious casualties in a situation like that.”

We’re taught that sexual assault is bad and perpetuators are bad, says Anna, “but we’re not taught how to talk to perpetuators and hold them accountable to their actions, keep them separate from safe spaces until a time—if a time comes—they’re able to come back to those spaces as a safer person.”

A “shit list” is flawed, defamatory, imperfect. But what else is there?

“We’re in this moment right now where this story is changing,” says Rahr. “The cultural acceptance and understanding of this is changing. And our legal system just hasn’t caught up yet.”

“Information I shared was always privately, in person. I think that's important, if at all possible. Ruining reputations is a bad idea for sure, but that's like saying Twitter is a terrible idea 100 percent because teens bully each other on Twitter. Women have always found ways to pass on information. We tell each other which hairdresser is bad, but we aren't allowed to talk about bad experiences with predatory behaviour? Women are smart. We can use that information as we want.”