Pandemics, as you may know, are ancient. And the ways we respond to them today are often still based on the ancient methods: quarantine, self isolation and physical distancing.

The biblical myth says “You remain unclean as long as you have the disease, and you must live outside the camp, away from others.” Interpreted one way, it lines up with current public health recommendations. Interpreted another way, it’s playing out on Halifax’s community Facebook groups, in the comment section on Instagram, in replies to tweets and on r/halifax.

To be cast outside physically: good for public health. To be cast out socially: dangerous to public health. The consequences of uncleanliness or illness leading to shunning, shaming and stigma are often greater than a single irresponsible barbeque or poor-taste Snapchat capture.

Robert Huish, associate professor in International Development Studies at Dalhousie University, says the notion that an individual or a group of individuals could flout the rules—rules that countless Nova Scotians have made sacrifices over the past year to live within—"builds a sense of anger.”

And the problem is that “when societies or communities are angry, it’s a very risky and delicate thing because sometimes that anger can be channelled in absolutely terrible ways that can create more harm than good.”

For the last year, Huish has been researching stigma in Nova Scotia during the pandemic. Throughout each wave, his research has shown a different focus of collective stigma: Asian communities, out-of-province plates, people aged 18-35—who, based on their identity, are perceived to be “doing wrong to society and then as a result society reacts in a negative and harmful way against that group.”

This third wave and its social-media fuelled cancel campaigns “is actually quite alarming,” says Huish.

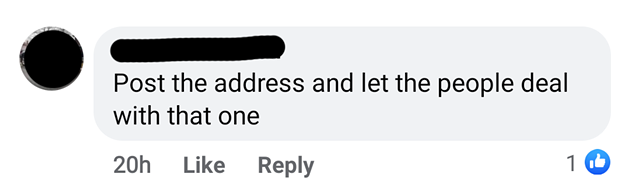

Nova Scotians are sitting behind their computers, phones and tablets unleashing their fury—or is it betrayal?—into the void that is the internet. It feels good, therapeutic. Someone likes their comment, replies with encouragement, community is built.

But what we’re seeing in this recent third wave, warns Huish, is a “scaling up” of the tacit shaming. And, he says, “people have erroneously made the conclusion that some sort of vigilante justice—whether it's shaming online or directly intimidating people who’ve done wrong—is somehow going to benefit public health.

“Straight up, that’s not how it works,” he says. “This is not Gotham City.” And no, dear commenters. You are not Batman.

It doesn’t work because when people feel threatened, when they feel like their neighbours are going to narc on them, when they’re not sure if they’re doing the right thing, when an angry mob has shown its face on Halifax’s tight-knit social media ecosystem, they are driven underground.

And that’s a problem, says Huish, because what’s really making anti-COVID efforts in Nova Scotia strong is getting people involved in the process. Mass asymptomatic testing, thousands of volunteers, collective responsibility and collective participation.

When you signal with your online or offline behaviour that someone should be shunned or isolated, that someone doesn’t belong here—easy for a place with a history of labelling those folks as “come from aways”—you splinter community. Viruses love that.

“They love it when communities aren’t working together. That’s when they really take advantage.”

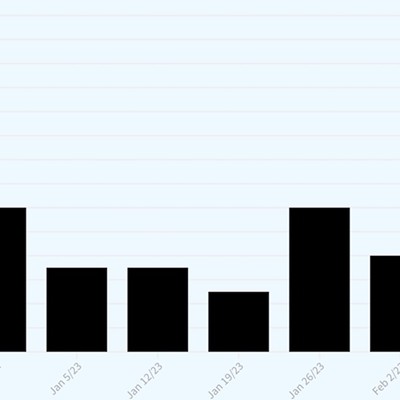

And working together is hard. It requires a lot of work, to deal with the frustration and the emotion and decide to be inclusive and have trust in your community. In a place where there are fewer than six degrees of separation—like Nova Scotia—the stakes are even higher. The scale could tip at any moment. We’ve gone from 42 active cases to 598 active cases in two weeks. Life was good and now it’s not.

And while mobs call for the public flogging of a group of uni students or family from Ontario that’s not even here anymore—if the social media rumours are true—we’re also seeing the highest rate of testing in the country. Some are screaming from their phones, but many more are showing up at testing centres and participating in the process. That’s the secret ingredient.

We’ve learned a lot about shame in the past few decades. Brené Brown’s shame research is apparently the first of its kind, and her meteoric rise to fame tells us she’s struck a chord in our world laden with recovering Catholics and daughters whose mothers micromanaged their own insecurities through the vessel of their offspring.

We’ve learned that shaming around sex doesn’t stop people from having it. We know that shaming athletes doesn’t make them perform any better. Coaches have stopped berating players who are having a bad game—not just because it’s mean and feels like shit, but because it doesn’t work.

When a player isn’t “cutting the mustard,” a strong team recognizes that the most vulnerable just needs assistance, so that everyone can benefit. Nova Scotia’s Covid success exists because there’s been a sense of “all alone, all together,” says Huish. A collective fighting for the same team of one million.

Being kind in the face of unfairness in a pandemic can be “damn hard,” says Huish. Especially for someone who is sick with COVID in Nova Scotia right now. They’re shaking their fists at the sky saying “I followed the rules, how the hell did I get sick?”

The hard work is knowing “these rules aren’t perfect, but they’re the best we’ve got.”

They’ve been around for centuries, after all.

If someone you love isn't responding to the pandemic the way you think they should be, please don't let your response be shaming them for feeling that way.

— Caora McKenna (@caora_mck) March 18, 2020

Shame is a quick route to isolation (emotional) and that's not the kind of distancing we're after!

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly attributed the quote from the bible to a character named Leviticus. Liviticus is actually just a chapter in the bible, not a character, so it was removed.