Cops make terrifying villains. They’re trained in the use of physical force. They know how to find people who don't want to be found. They own, and bring home, guns. For the kind of person who craves control, it's an attractive job. And if control is one of the main drivers behind domestic violence, asks Alex Roslin, is it any surprise that cops would be violent at home?

An award-winning journalist, Roslin’s investigatory writing has appeared in the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star and the Montreal Gazette, among other outlets. He’s been writing about police-related domestic violence for 15 years and recently co-authored Police Wife: The Secret Epidemic of Police Domestic Violence. The author and his research suggest Canada’s police departments are unable or unwilling to acknowledge the blight of domestic abuse within their own ranks.

The Halifax Regional Police department was one of only two municipal police organizations in Canada who spoke with Roslin for his book and offered data on domestic violence complaints against their officers. Even then, it was only for cases that resulted in disciplinary actions. There were nine of those incidents between 2010 and 2014.

That’s a low average for HRP’s roughly 500 sworn officers—well below the domestic violence rates for the general public (which hover around six percent).

“Chief [Jean-Michel] Blais, to his credit, actually said the level of police domestic violence is higher than in the wider population,” Roslin says. “I haven't heard a lot of police officials actually say that or acknowledge that. The Toronto police department actually refused to return any of my calls or even answer Freedom of Information requests for data.”

In his research Roslin discovered only 10 RCMP officers in Canada faced formal disciplinary actions for domestic violence from 2008 to 2013. Only three of the 10 cases led to criminal charges. Harsher penalties were handed out to officers in the same period who made false statements or committed theft. Those Mounties were often dismissed, or ordered to resign.

Research done by American sociologist Leanor Johnson in the late 80s found that 40 percent of male police officers interviewed admitted to violent behaviour against their spouse or children in the previous six months. Applied to Canada’s 70,000 police officers, Roslin writes that means there could be as many as 28,000 cops nationwide who are violent at home. So why aren’t police being arrested left, right and centre?

Arrested in December, 2012 for sexual assault. Arrested again in April, 2014 for breaching release orders, and again in May in Newfoundland. His trial for the sexual assault charge resumes January 4. As a cadet, Mosher was dismissed from police training programs but later reinstated. The four-year Halifax police veteran was charged with domestic assault his first year on the job in 2009. He was placed on administrative leave at the time, but reinstated when the Crown withdrew charges.

Jason Richard Murray

Charged with two cases of assault earlier this year, stemming from incidents in 2013 and 2014. The six-year HRP employee is currently on administrative duties, awaiting trial in January.

Tyler Andrew Anstey

Suspended with pay back in June after being charged with assault and forcible entry. The 13-year veteran of Halifax Regional Police will stand trial next summer. He’s pleaded not guilty.

Kenneth James Taker

Charged with sexual assault this summer over allegations of inappropriate touching and assault made by a civilian employee and a female RCMP officer during a three-day RCMP meeting at White Point Beach Lodge in March. The Dartmouth RCMP sergeant is still awaiting trial. He’ll be back in court this week to enter a plea.

Jefferey Hennessey

Facing charges after two separate incidents of alleged domestic violence in the same night. The Cape Breton Regional Police constable stands accused of assaulting two women on August 1 outside a fire hall and then later a pizza shop in Dominion.

Arrested in 2013 on three charges of domestic assault against his girlfriend. The Sackville RCMP officer told CBC that the SIRT investigation was “out of proportion.” The Crown stayed charges against Simmonds back in June.

Luc MacInnis

Charged with assault in 2012 after SIRT investigated two domestic violence complaints. The charges against the Antigonish RCMP officer were dropped the following spring. The Crown didn’t enter evidence because a conviction seemed unlikely.

Natasha Dantiste

Assault charges against the RCMP constable were dropped. Contradictory evidence made the Crown feel a conviction was unlikely.

Christine Marion Bonnel

Arrested in 2012 on domestic violence complaints. The Bridgewater Police constable had been on leave from the force for the previous four years. The Crown dropped the charges in favour of a peace bond.

After pleading guilty to a “sustained assault over 20-25 minutes,” Marriott received a conditional discharge of nine months probation and is on a DNA database. After his probation period ends, he won’t have a criminal record. Marriott was originally suspended with pay by HRP, before returning to administrative duties. Statements about other past incidents involving Marriott were made to investigators, but there wasn’t enough evidence to pursue further charges.

Arrested in 2013 for an alleged incident of domestic violence at the HRP constable’s home. He was acquitted last December, when the Crown failed to prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Dennis Dale Kelsey

Found not guilty last November after being accused of non-consensual sexual touching with a woman the now-retired Halifax police officer visited one night in 2013. The Herald reports there wasn’t enough evidence to satisfy the judge beyond a reasonable doubt.

“There's a huge range of tricks and steps that police officers take to derail these investigations before they ever get to a criminal investigation,” says Roslin. Investigating officers, for example, can intimidate and pressure spouses not to file an official complaint. Even independent investigatory bodies can fall prey to prejudices, Roslin warns. The investigators with Nova Scotia’s Serious Incident Response Team (SIRT), he points out, are two retired RCMP officers and two full-time police officers seconded to the unit (one from HRP and one from the RCMP).

“You have four people that either still have links with their existing agency, or worked there their whole life. In that kind of situation, is it going to be much better than police officers investigating each other in the department?”

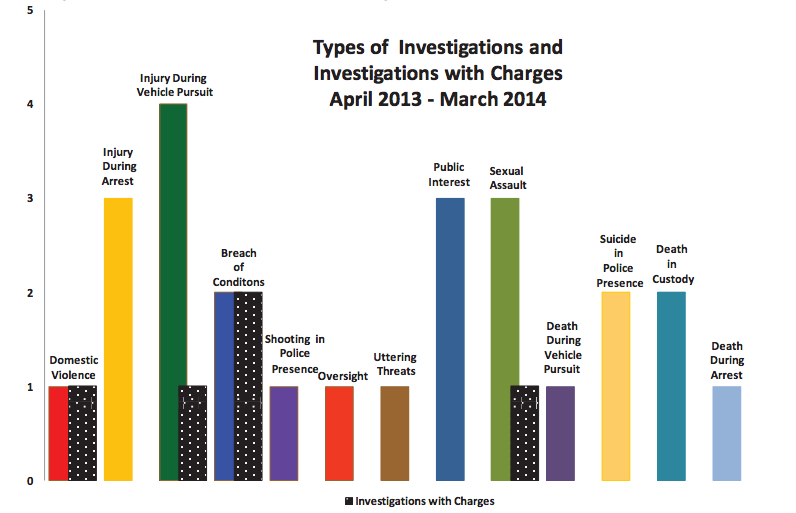

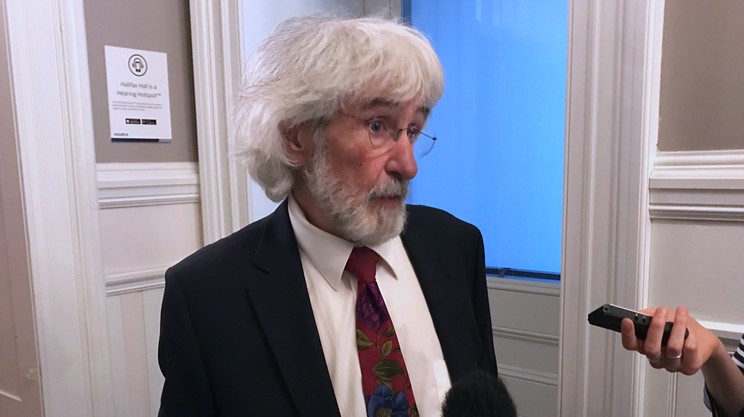

Founded in 2012, SIRT investigates all matters involving death and serious injury arising from the actions of a Nova Scotian police officer. Unlike some other provincial investigatory bodies in Canada, its mandate includes sexual assault and domestic violence complaints. Police chiefs and the local head of the RCMP are required by law to refer all serious incidents in the province to SIRT. The team operates independently from the Justice department and under the watch of director Ronald J. MacDonald, who’s blunt in responding to Roslin’s criticisms.

“He doesn’t understand the business at all. I would ask Mr. Roslin, who does he want investigating these cases?," says MacDonald. "If you want a really good brain surgeon, you don’t get someone who just graduated med school. The reality is we need people who’ve been trained as police officers to do it.”

According to CBC, domestic violence complaints accounted for more than a quarter of the cases SIRT was working on in its first 12 months of operation. That number’s since dropped off. The organization's upcoming annual report (which MacDonald quoted over the phone), says SIRT investigated only one domestic violence complaint in the last 12 months.

“Now, we have some review cases that don’t turn into investigations, and there wouldn’t even by a press release on,” says MacDonald. “We might have a third party say ‘So-and-so was doing X to their spouse.’ Which we investigate, but aren’t able to get any evidence to back up that report.”

The number of cases involving police domestic violence are proportional to the larger population, MacDonald says. But that doesn’t mean the Crown prosecutor of 17 years believes there’s no “secret epidemic” of spousal abuse—or that it’s limited to cops.

“It’s a secret epidemic in every line of work. There are many, many cases of domestic violence that go unreported no matter who or what the person does.”

In 1999, the International Association of Chiefs of Police developed a “model policy” on abusive cops that it recommends for its 100 member countries—including Canada. It calls for a “zero tolerance” approach, and recommends automatically firing officers convicted of a domestic violence criminal offence. It also suggests better screening practices for new hires to identify those with abusive tendencies or a history of violence, as well as closer monitoring of early warning signs and severe punishments for officers found to be interfering with a police domestic violence case.

Sixteen years after being drafted, the model policy remains largely ignored. According to Roslin, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police hasn’t endorsed or studied the IACP’s recommendations. No police department in the country has a policy to automatically fire an officer convicted for domestic abuse. Not just someone who’s charged, mind you, but a police officer who's been convicted.

Jean-Michel Blais says he wasn’t aware of the IACP’s model until Roslin brought it up during interviews for his book. The HRP chief stresses there are codes of conduct that allow his officers to be dismissed if found not fit for the line of duty. The Nova Scotia police act regulations also allow administrators to suspend an officer without pay. That provision has been used twice in the last three years. But mandatory disciplinary actions like the automatic dismissal recommended by the IACP aren’t nuanced enough to help, says Blais.

“You think about the worst case scenarios...in the majority of those cases the individual would be dismissed. However, when you get into a situation where you’ve got a couple where he’s been drinking and he ends up pushing—we’re talking the lowest level of domestic violence—and that technically is an assault. Does that mean that individual deserves to be fired?”

Every case, Blais says, should be looked at in its own context.

“If we expect our police officers to be fair, equal and unbiased with members of the general public out there, then when [the officers] get in trouble, and they have problems then they too have to be treated with fairness and intellectual rigour.”

But should they? For some, the authority and power wielded by police means they should be held to higher disciplinary standards than the public. Otherwise, cautions Roslin, those officers will find ways to game the system.

“Every level where there's discretion given to police officers, then that's where they squeeze a way out,” he says. “It's still a troubling issue because these are public servants whose job it is to enforce the law. If they're themselves engaging in criminal activity and being protected by fellow law enforcement officers, then that's a huge concern. It's a gross misconduct.”

Blais himself acted as director in charge of prosecution for the RCMP’s internal disciplinary system before coming to the HRP. Out of the 75 cases he prosecuted, Blais says there were only four that involved domestic violence. One was an officer throwing VHS tapes.

“Which, for a normal person, shall we say, would have resulted in nothing. Whereas for this individual, as a result of some other aggravating issues, he ended up being kicked out of the RCMP.”

Other cases weren’t so minor. In 2009, he co-prosecuted the internal disciplinary hearing that booted out Kevin Gregson. A month later, Gregson stabbed and killed Ottawa Police constable Eric Czapnik.

An investigation by the Ottawa Citizen found that over the five years previous Gregson had remained on RCMP payroll “as he was disciplined, suspended and demeaned.”

Chris Cobb writes that the Mounties couldn’t force an emotionally troubled officer like Gregson to seek treatment, but they could have stopped paying Gregson, or threatened him with dismissal. The Citizen’s investigation “suggests they did neither.”

During his interview in Roslin's book, Jean-Michel Blais highlights workplace stress as one of the main factors behind police domestic abuse. Speaking with The Coast, he walks back that position.

“I think there’s a constellation of reasons,” says Blais. “The vast majority of police officers are able the handle the stresses, deal with the challenges.”

Nevertheless, the police chief says there are inadequate substance abuse and mental health resources available to his officers. Currently HRP is in the process of developing a new wellness program to address those issues.

In Leanor Johnson’s research, 36 percent of police officers admitted to problems with alcohol, 30 percent reported suicidal thoughts and nearly 90 percent of spouses wanted more from departments in the way of psychological counseling.

From an anecdotal perspective, Blais doesn’t see police domestic violence as a worrisome trend—at least not locally. He says there may be a tendency to overestimate the problem, but admits Canadians know far too little about the subject.

“If we don’t know, how can we ever underestimate it? It’s one of those things that needs to have further research done on it.”

But where Blais sees a constellation of possible reasons for police domestic violence, Roslin only found three; control, derogatory attitudes towards women and the impunity officers have in getting away with crimes. Eliminating those issues, he says, isn’t going to be easy.

“It just starts from the top and we also have to go deeper than even just police departments. What kind of community support is there for dealing with domestic violence? We have to look at problems like social inequality, which help create the conditions in which police domestic violence occurs.”