Amy Goodman has been called “as close to the

The host and executive producer of the acclaimed Democracy Now! news-hour has been lauded with dozens of prestigious journalism awards for her dogged reporting. Goodman has been attacked by soldiers while covering the East Timor independence movement, documented violent clashes between villagers and the Nigerian Army organized by the Chevron Corporation and faced riot charges for her work broadcasting from the Dakota Access Pipeline protest. Along the

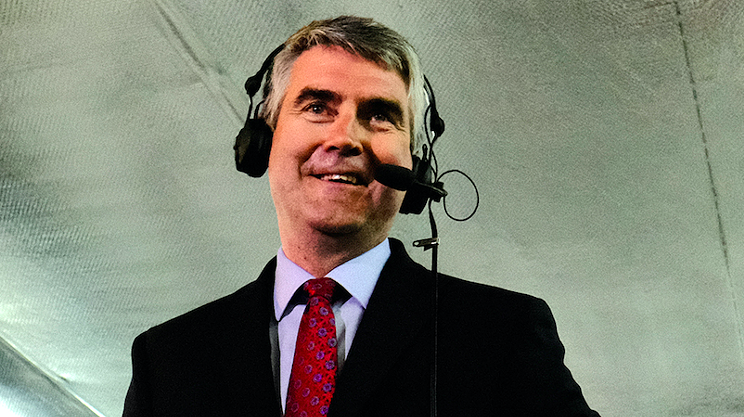

Goodman will be in Halifax this Saturday giving a talk as part of Fernwood Publishing's 25th anniversary. She recently spoke with The Coast about the perils of corporate media, Donald Trump’s tantrums and what gives her hope. Her answers have been edited for style, clarity and length.

A journalism student recently lamented to me how much emphasis her professors were putting on unbiased objectivity. Given the political climate in North America, the student felt an adversarial media is more important now than ever. Where do you think the line between journalist and protester falls?

I mean, it is our job to challenge those in power. We have to be fair, we have to be accurate, and it's critical that we are there to challenge what's being said. It's also our job to go to where the silence is and to provide a forum for people to speak for themselves. That's where Democracy Now! is also quite different. We don't have that small circle of pundits that you get in all the corporate networks who know so little about so much, explaining the world to us and getting it so wrong. We have to go to people at the heart of the story and hear them describe their own experience, shape their own narrative. That's absolutely critical.

When president Trump attacks Black athletes and says they should be fired if they take the knee during the national anthem, it's absolutely critical to hear from those athletes. When he tweets about that obsessively all weekend but doesn't tweet once about Puerto Rico—which is a colony of the United States and is in the midst of a catastrophe as a result of Hurricane Maria—we need to hear from Puerto Ricans describing not only the catastrophic physical situation they're in, but how their status as a territory of the United States is hindering their ability to recover from their storm. When the president of the country is a climate change denier, it is absolutely critical that we not only show the evidence of why he is wrong but go far beyond to talk to people on the ground all over who will describe what is happening. So the activists are often the most important analysts to have on because they're on the ground and they know what is happening there.

You’ve said corporate media has largely become a megaphone for those in power. Do you think corporate media can ever be an effective watchdog against people like Trump?

You know, I've wondered why the president doesn't lay off attacking the media. Because if he did it for just a week, they would wrap themselves around him. It is because he's personally attacking them that they're standing up and, well, sounding like Democracy Now!. So the media has been—because he's calling them out by name—defending itself. That's important, the right to do that. But, when it comes to war, when it comes to bombing other countries, even with president Trump who they've been critical of, they circle the wagons around the White House.

You think of when the US bombed the Syrian air base, and I think it was Brian Williams of MSNBC—not Fox, MSNBC—talking about the beauty of the bombs and the weapons, quoting Leonard Cohen, which I think would make him turn over in his grave. When president Trump dropped the largest non-nuclear bomb in the history of the world

The media has to be critical, especially in times of war, because we're talking about life and death. And then, the issue of climate change. In the US now, the cable news coverage [of hurricanes] is non-stop. It was 24-hours-a-day. In this wall-to-wall coverage of the hurricanes, they almost never raise the issue of climate change. Almost never. This is when it matters. This is a critical moment to talk about this.

I don't know if it's because when you watch CNN, every six or seven minutes they break for a commercial and among those commercials are, you know, “Brought to you by the American Petroleum Institute.” This is why independent media is so important. Again, there are occasional exceptions, but for the massive amount of coverage they're doing, almost never. I personally think the meteorologists should not even be able to be certified if they don't raise this critical issue, which is determining the fate of the planet. When it comes to the coverage of hurricanes, you have to ask, if we had state media, how would it be any different?

How much of that is driven by the corporate influence, and how much comes from either untrained journalists not understanding the story themselves or not wanting to aggravate the members of the buying public that watch?

Like any other issue, you just present the facts. You can even have debates around these issues. They're not addressing it at all. I don't think it's a matter of direct censorship, where a corporation calls up a local reporter or a national reporter and says, “Don't do this.” I think it's a kind of shared consensus between the owners and their advertisers, their corporate sponsors. And reporters know how to get ahead in their newsroom.

Many people have talked about Trump creating a chilling environment for the press. You were arrested for covering the Dakota Access Pipeline while Obama was still in office, and you were arrested at the 2008 Republican Convention. How much has really changed for journalists who report on stories outside the mainstream media?

When it comes to the Dakota Access Pipeline, I very much want to talk about that in Halifax when I come

Ultimately,

As reporters, yes, I was arrested at the Republican convention. We were just covering an anti-war protest. I was actually on the convention floor when my colleagues, two of our reporters, got arrested covering the protest. I simply ran to get them released and when I went up to the riot police and told them I needed to have our reporters released, that's when they twisted my arms behind my back and ended up pushing me to the ground and arresting me. Ultimately we made a major settlement with the police, to train the police differently.

For North Dakota, we filmed the dogs being unleashed on water protectors and came back to New York. It was when the North Dakota governor called out the National Guard that quietly they issued an arrest warrant for me. I didn't even know it at the time. I had come to Canada, to the Toronto International Film Festival, and I was speaking after a film on the muckraking journalist I. F. Stone. I was in the midst of my speech when I got a text that I was under arrest. I had to race to the airport to try and get back into the United States before it got into the system.

We went back to North Dakota a few weeks later. I didn't really take that arrest warrant personally. I thought it was a warning that was sent to all journalists: Do not come to North Dakota. Which is exactly why we had to go to North Dakota. We were calling their bluff, and they dropped the charges and quashed the arrest warrant. But then they tried to bring more serious riot charges against me because I recorded what had happened. I faced up to a year in jail because of this. But because there was tremendous focus then—the NY Times, BBC, Al Jazeera, even Vogue Magazine was covering this now—it was then that they ultimately decided not to bring the charges. It was not only me they dropped the charges against. It was a number of Native Americans who faced felony and misdemeanour charges who were going to court that day. That just shows what happens when the media shines its spotlight in the right direction, around issues that really matter. These are critical issues and, no, it hasn't changed from a Democrat to a Republican president, except that Trump is promising to crack down further on journalists and that's extremely serious.

For new journalists or those entering the field, what would you recommend they do to protect themselves?

That's why we went back to North Dakota because I really felt especially for young journalists it was critical. They don't have the resources, the institutional backing to go someplace and think they'll end up in jail. We really had to challenge the state in this case so that message wouldn't go out: if reporters go there they will be jailed. It is such an important, noble profession and yes, young people should become journalists. It's absolutely critical. It's how we hold those in power accountable.

Your talk is entitled “Stories of Democracy, Resistance and Hope.” Those first two—democracy and resistance—we hear a lot about. What gives you hope?

The confidence people have that they can make a difference is deeply inspiring. To interview the great environmental activist, Hilton Kelley, in Port Arthur, Texas, who is trying to save people as his city is flooded, and still he's taking a phone call and talking about the immediate issue of people's survival and the long-term issue of how we can take on climate change and make a difference, that's astounding. People's courage always inspires me. The people of East Timor, long occupied by Indonesia. They believed they would be free, even though a third of the population was killed. The Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, you know, deeply inspirational. They did not have the support or have access to the corporate microphones of the media so they would challenge the politicians, the candidates and take the mic themselves so they would be heard. It's really very inspiring to hear people in their communities not giving up hope. That's what gives me hope.

Saturday, September 30, 2017

7-10pm

Ondaatje Theatre, McCain Arts and Social Sciences Building

6135 University Avenue

$20