When it comes to affordable housing in Nova Scotia—or a lack of it—definitions are fast and loose, and who needs help often gets lost among departments and jurisdictions.

HRM planner Jillian MacLellan says it's "such a big issue that trying to find the best place to start or where you're going to be most effective in your changes is one of the most difficult parts."

The majority of responsibility for housing falls on the province. It's in charge of rental increase rules—which are minimal: Your landlord can increase your rent however much they'd like as long as you're given four month's notice—requirements for building types and quality of housing.

But one thing Halifax does have control over is the housing supply. Since the 2006 regional plan, the city has been slowly working towards some form of urban densification. The 2009 HRM By Design plan looked at densification in the downtown area of Halifax, 2013's Stantec report talked about the cost of developing urban versus suburban versus rural and, today, the holy-grail Centre Plan is as close as it's ever been.

"You're going to start to see a fair bit of development, a lot of it will be rental housing," says Eric Lucic, manager of regional planning with HRM, "which could help soften the market and reduce the low vacancy rates that we're currently at."

CMHC says that vacancy rates in 2018 were the lowest Halifax has seen in years—1.6 percent. Increased demand, caused by a rising population and more seniors entering the rental market, has outpaced the creation of new housing supply. Since 2006, the population in HRM has grown by over 45,000 people but only 11,270 units have been added to the rental market. (While not all these new Haligonians went on to rent—many bought homes—HRM says about 40 percent of the city's population are renters.)

A general economic rule is that stagnant supply plus increased demand usually results in an increase in prices. The average rent increase reported in The Coast's Renters' Survey was five percent (with 27 percent of respondents reporting a rent increase).

A spokesperson from Service Nova Scotia referenced that CMHC data, saying that the 1.9 percent average price increase from 2017 to 2018 on two-bedroom builds in the province "indicates that rents in Nova Scotia are reflective of market conditions and are not being dramatically increased."

CMHC also defines affordable housing as spending less than 30 percent of your income on rent and housing expenses. When looking at income in the Renters' Survey, 62 percent of respondents would spend more than what's affordable on the average rent.

"I do think Halifax is unique in the sense that our wages are lower compared to the rest of the country, where rents are on the higher side or comparable with the rest of the country due to the presence of quality universities and other reasons as well," says MacLellan.

As a census metropolitan area, Halifax ranks 24th on Statistics Canada's median household incomes, but jumps nearly 10 spots to 13th on average rent price (in January 2019 for one- and two-bedroom units).

When asked about affordable housing, the province mentioned the 2,300 low-income individuals receiving rent supplements, work to improve the waitlist for public housing, programs helping Haligonians who are homeless or at risk of homelessness find and keep housing, and says that the Residential Tenancies program continuously monitors the rental sector for trends and changes in market conditions, including rental and vacancy rates by specific geographic areas.

Lucic thinks the Centre Plan's goal to intensify the regional centre could have a snowball effect on housing affordability. Increasing density will mean transit can improve, fewer people will need to depend on cars, which will hypothetically free up income to go towards housing, he says.

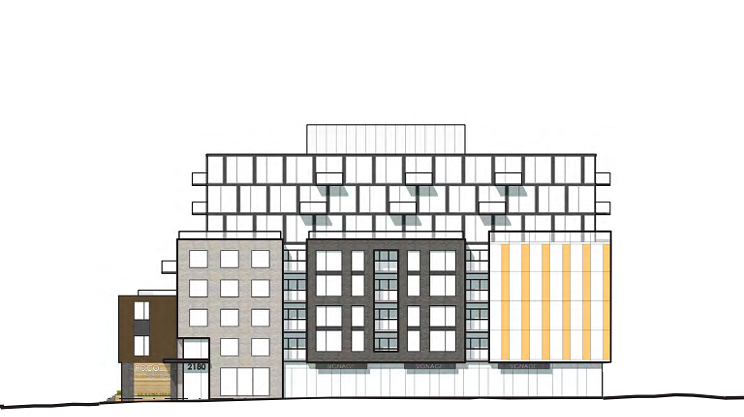

They've also worked to waive permit fees for non profits, and made it so new developments don't need to construct parking (like case 20632 on page 4), "So in theory, those units should be coming in at a lower rate because they're not having to provide parking, the cost of construction, therefore is lower" says Lucic.

HRM hopes the density bonusing program—which sees cash from developers wanting to build bigger than 2,000 square metres going directly to a fund for affordable housing—will make an impact. What the fund's initiatives will look like won't be decided until after the centre plan is finalized in early 2020.