Quilts. Please don't turn the page. I know quilts are not an easy sell. While they're comfortable to snuggle in, or remind you of your grammy, no one could have predicted that an exhibition of quilts would break museum attendance records across the United States, or be declared by Michael Kimmelman, chief critic for the New York Times, as "some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced. Imagine Matisse and Klee arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South." No one could have known that quilts would adorn a set of US commemorative stamps, or be captured as intaglio prints to hang in American embassies across the world.

But these are not ordinary blankets: These are the quilts of Gee's Bend. Some of these quilts, along with prints and inspired sculptures, are now at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia for the show Mary Lee Bendolph: Gee's Bend Quilts and Beyond. To date, Halifax is the only Canadian city to host these joyous, abstract, colourful works of art. It's a movie-ready story of creativity and community that financially empowered forgotten, poor women—ultimately challenging what western cultural institutions define as art. And there's a connection to African Nova Scotian culture that's too familiar to ignore.

Gee's Bend is a tiny, isolated southern Alabama community cupped by the Alabama River. In 1816, Joseph Gee, originally from North Carolina, created a 10,000-acre cotton plantation there. When he died in 1824, he left 47 black slaves. In 1845, two of his nephews owed money to another relative, Mark Pettway. As a settlement, they gave Gee's Bend to Pettway and more than 100 of Pettway's slaves actually walked the brutal distance from North Carolina to their new home. After the Civil War, the freed slaves became tenant farmers for the Pettway family and many people in the community today still carry the former slave-owner's surname.

The Depression of the late 1920s hit Gee's Bend hard and left many people close to starvation. Although life subsequently improved with President Roosevelt's relief programs and funded housing, the isolated Bend didn't receive electricity until the 1960s, or indoor plumbing or telephones until the 1970s. Though forgotten by many, Martin Luther King visited there in 1965 to deliver a sermon at the Pleasant Grove Baptist Church. Many Benders joined King in the growing civil-rights movement, risking violence and jail time by attending protests in the not-so-nearby town of Camden. After King was murdered, their mules carried his casket. Before that terrible day, one of these protesters was a young woman named Mary Lee Bendolph, who had dreamed of King's visit—one of many prophetic visions she has experienced in her lifetime.

When you first meet Mary Lee Bendolph, even though you're a stranger, she will probably hug you. Without any self-consciousness, she will hug you tight and you will feel a warmth that is otherworldly. The 72-year-old Bendolph will tell you she became pregnant at 14 and, sadly, had to leave school at the sixth grade, then proudly declare that two of her children finished college. Bendolph might tell you more about her dreams—she remembers having a vision as a child that one day she would meet many people, something that she "didn't have a chance to do when I was young," and that they would come just to see her. She laughs easily—giggles sometimes—and she loves to sing: Occasionally Bendolph breaks into a hymn, filling the gallery with an earthy sound that rises and balloons in the space, causing other conversations nearby to halt briefly.

Bendolph is sitting near one of her quilts made out of recycled denim workclothes. She could use new materials, but re-use is a visible demonstration of her unwavering values.

"Almost everything I use mostly is the old material, some that people don't want but they loved it and now I love making something out of it so someone else can love it," she says.

Designed in strips—similar in style to West African textile patterns—this quilt's tough denim seamlines build into strong, triangular-shaped mountains and faded, worn spots create tiny light sources. Dark indigo patches, like cave entrances, are spotted throughout and are mixed with pretty flowery strips, perhaps from an apron. Their lightness is juxtaposed against bright red squares and lines that both pop and demonstrate Bendolph's natural understanding of design principles.

From a distance, it looks like a Paul Klee painting, or a Cubist Picasso landscape. Although this is a relatively new piece from 2002, Bendolph's castaway quilts are still imbued with the same traditional African-American aesthetics and geometric exploration for which she, and the other Gee's Bend quilters, are famous.

"When I first started piecing quilts—my momma taught me how to piece quilts—all of my quilts were made in the shape of a quilt. I can't make pattern quilts, she tried to teach me but I was like, "That takes too much,'" Bendolph laughs, throwing her head back at her own joke. "So I just put something together and sometimes it comes out so beautifully." She shifts her hands around her lap in demonstration. "I put two pieces like this, then two more. I take another block. Sometimes I put all the pieces together and sometimes I just go with it. Piece on piece. And if it doesn't fit there, I just put it in some other place."

She waves her hand around the room at varying colour fields of greens and yellows, of reds and blacks, of bold blocks of corduroys and tweeds.

"The most important thing is the colour. Can you see that?" She laughs at the obvious answer. "Colour makes you uplifted. Puts a smile on your face. You know how sometimes you can look at something it can be so dull-looking but if there's colour in there, it puts a smile on your face. It's like when the sun's shining, it makes you feel bright. You have to keep your spirit up and that's what I always try to do."

The quilts of Gee's Bend did not begin as works of art to hang on museum walls—they kept people warm at night. But these patchworks of collected material provided opportunities for generations of women to spend time together, to share beauty and new ideas. The women did not use patterns or fixate on stitch perfection, but all quilters agreed that each design should be unique.

Bendolph remembers, "When you're all working together, everyone does it a little different, it inspires you a little more, to go a little further. It was like that when we were quilting—it was me and my momma and my aunt together. When the children would go to school, we would get together. It would be cold, sometimes so cold you'd have to wrap something around you. We would sit there quilting and singing and praying. Telling tall tales, talking about each other sometimes. Well, you just don't sit there and say something that's just not true," she adds by way of explanation. "You always try to do right."

In the late 1960s, the Freedom Quilting Bee provided some money for the community—the women would sell quilts to stores like Bloomingdale's and Sears, but retailers wanted traditional, stitch-perfect blankets, not the improvisational designs these women created. And perhaps life would have carried on as such if it hadn't been for William Arnett, a collector of African-American art, who, in 1998 while doing research for a book, stumbled on a small photograph of a quilt by Annie Mae Young.

"The quilt had a freedom of design to it that I wouldn't say was rare—because I've subsequently found hundreds, if not more, of equal importance," Arnett says. "But it was a rare quilt in terms of my own experience at that time and in terms of what had been published. I have a pretty good antennae for such and thought, "If there's that, what else?'"

Arnett tracked Young down to Gee's Bend, showing up unannounced at her door. It's fun to imagine what she must have thought of this middle-aged Southern white man, with his generous frame, nape-grazing gray hair and intense words, offering to buy her quilts. He took several of them to Houston's Museum of Fine Art, where the first exhibition opened in September 2002. And although Arnett thought the quilts were special, he, too, was astonished by their instant popularity.

"The Gee's Bend phenomenon is part of a much deeper, wider spectrum of visual arts that are part of the cultural language created in secrecy during slave times by people who were deprived of the rights to have any culture or cultural language," he says.

Arnett likens public acceptance of the quilts to the slow but unstoppable journey that black southern music like jazz, blues and rock 'n' roll faced 50 years ago. Although he acknowledges his own place of white male privilege, Arnett thinks that the days of educated white American men ruling in any particular area, including visual art, are dwindling.

"Some of the things that white people once claimed only white people can do, like play golf, that's probably the last thing people expected to be dominated by a black person. Or tennis. Who would have thought that two sisters could have been the best in the world? And they were," Arnett says. "There's one thing that's left that's still closed—the mainstream art institutions. Gee's Bend was the only aspect of southern black culture that was able to sneak in and make an impact."

As the popularity of the quilts and the curiosity about their makers grew, Arnett and his four sons formed Tinwood Alliance, a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting under-represented artists, with a little financial and promotional help from his friend, Hollywood icon Jane Fonda.

"Jane is one of those rare people who really cares about things. She cares about people, she and I had been friends, and she saw us struggling and said to me, "How can I help? Give me a one-sentence description of what you're doing.' So I said, "Basically what we're trying to do is level the playing field for a segment of our culture that's been totally deprived of its own voice and its own ability to show itself as it really is, and it's surrounded by and dominated by a Eurocentric system that doesn't want any part of it. We want to do books and exhibits that give this culture an opportunity to compete.' She said, "Count me in.'"

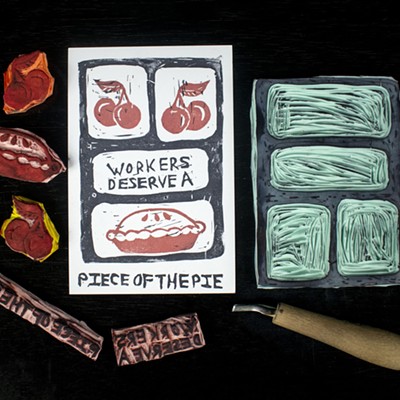

Tinwood is also a publishing company that develops high-end, well-designed books, documentaries and other materials about vernacular artists—Arnett prefers that term over folk or outsider artist, because, according to the Tinwood website, "their artistic expressions convey deep cultural meanings and communications." The Alliance also assisted the women in creating their own collective that markets and sets fixed prices for the quilts. The maker receives part of the proceeds and the rest goes back into the collective to cover expenses and to be distributed to the other members.

"The whole history of this kind of work is white people going around playing one against the other. I'll give you two dollars for this—if you don't sell this, I can go buy one from her for two dollars. Keep them isolated, keep them unaware," Arnett says. "When I met the women of Gee's Bend, the most that anybody had sold a quilt for was $35. That was rare—normally five dollars, 10 dollars, two dollars. Now you have Gee's Bend quiltmakers getting $20,000 and more for a brand-new quilt. Some of their older quilts are valued in the hundreds of thousands. And so it's a good success story."

Like William Arnett, David Woods travelled door-to-door looking for quilts. Back in 1997, when Woods first put a call out for African Nova Scotian artists to participate in an exhibition, only six responded. So he visited communities, looking for works.

"I'm a grassroots warrior. My heart and passion belong to the everyday folk and the things that everyday folk do, so that allows me to be able to interact with people," Woods said in an interview last year. "Especially with the black community—our creativity was always very proletarian. We weren't in galleries, we weren't having these high-end aspirations, but people were carving things, doing all kinds of stuff. I love the trajectory, the dialogue that comes with that, on how we've interacted with art and music we've created out of our experiences."

As he travelled through the province, a woman in North Preston suggested that Woods should include quilts. "It just never dawned on me. I wasn't aggressively rejecting quilts, it was just non-art, not on the radar," Woods says, laughing. "Then everywhere I went, I started asking about the quilts and realized that quilts had the greater continuity of tradition than certainly painting. I could get quilts from every decade, it was more universally spread throughout the community. When I realized how deep and how exciting this was, we formed a group out of the Black Artists Network called the African Nova Scotian Quiltmakers."

While the Gee's Bend aesthetic is more freeform and jazzlike in nature, African Nova Scotian quilts are much more focused on tradition and technique, although there are a growing number such as New Glasgow's Myla Borden—who created a quilt of one of Woods' paintings, entitled "Seaview"—who design quilts to represent their own community's stories. But, as Woods points out, the origins of black quilting are the same.Growing out of slavery, women were taught the skill to serve their masters, but it grew into a valued subversive form of creative expression. In fact, some historians believe that quilts were used as a means of hiding communication symbols during the Underground Railroad.

"We come from a quilt-making culture. Quilts were used in the house up until the '60s, '70s. We didn't buy a blanket or go down to Woolco, or whatever the department store, and buy a bunch of stuff. We made quilts," says Woods. "Raggedy ones, fancy ones for momma. Everyone grew up with that, and whenever momma needed help, she'd gather the children. It was just part of the culture."

When Woods was hired last year as the AGNS's first associate curator of African Nova Scotian Art—a contract which ends in June—Woods focused much of his efforts on bringing a smaller show of Gee's Bend quilts to Halifax. With no response from the Houston Museum of Fine Art, which owns the show, Woods contacted Arnett directly, who didn't know anything about the small Canadian Maritime province.

"The main reason we came is because these groups, these communities, were asking if we would come up here and do some kind of exhibit," Arnett says. "What's been so satisfying is to see how affirming it's been for the black cultural groups in Nova Scotia, that there's a parallel somewhere else that has succeeded." Pending fundraising targets, this summer there are plans for Bendolph and other Gee's Bend quilters to return to Nova Scotia to tour black communities and spend time with local quilting groups.

Before the glowing Times review of the exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York, there was a scathing Wall Street Journal article that called quilts "beaux-art blankies," suggesting that museums which stage these exhibitions are cheap and pandering to public approval. In 1993, before Gee's Bend, Arnett was criticized by Morley Safer on the television show 60 Minutes for his relationship with two self-taught Alabama artists, painter-sculptor Thornton Dial and sculptor Lonnie Holley, both of whom have quilt-inspired works at the AGNS. In his 2006 book The Last Folk Hero, Atlanta author Andrew Dietz presents Arnett as a controversial, paranoid and conspiracy-fearing PT Barnum-type character: Depending on who you talk to, he's either an exploiter or a saviour.

"It was the only way to stop this—they can't criticize the art anymore, or make people think it's no good because people can see it, so they can take the person who found it and documented it, and it's almost comical. It's a little too late now," Arnett says, although he does make bold statements such as one about how a resurrected Albert Einstein or Leonardo Da Vinci would think that the quilts are the finest art being produced today.

"I love the women of Gee's Bend, I love the quilts and I put a great deal of my life into it, so I have evidence I'm not just talking or capitalizing on its success. The Gee's Bend show is remarkable as it as, and it is remarkable, is still just a tiny piece of the puzzle. It happens to be a piece that was sneaked into the art world without the usual guardians that protect the mainstream art world and make it safe for white educated men to dominate it. Nobody took quilts from a little black community seriously. And then, when they tried to block the show and cut it down to size, it was too little, too late."

As Woods was busy promoting Gee's Bend and quilt-making events, he received a couple of emails from diplomatically unnamed experts who claim that there are no black quilt-making traditions because many of the patterns have European origins—although as Woods points out, a flying geese pattern means something completely different to an enslaved culture: It symbolizes freedom, not just a pretty bird. He is obviously agitated by the shortsightedness, but shrugs it off in light of the gallery's success in bringing this popular show to Nova Scotia. He knows that the spirit of the show transcends colour or class.

"It says, "I can make my own stuff, design my own stuff, follow my own path.' It's an open field of imagination and geometric shapes that go in different ways, that's one of the things that draws me to it, it's energizing and visually liberating for people."

Arnett agrees. "It's not an accident, it's not political correctness that made this happen. It's the need that people have to see something like this. There is very little being made today that can satisfy people on every level, not just on an emotional or passion level, but on an intellectual level, like this does."

Mary Lee Bendolph: Gee’s Bend Quilts and Beyond, until September 19 at the AGNS, 1723 Hollis, 424-7542.

Sue Carter Flinn’s fascination with quilts grew while she was working at the Textile Museum of Canada. She’s been a Gee’s Bend fanatic ever since seeing the exhibition in 2005 at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.