Stewart Legere was blissed out, listening to Fleet Foxes in Steve-O-Reno's. On his table was a double skim latte and one of those thick oatcakes starving artists eat for fibre. The date on the Chronicle-Herald was April 12, 2011. When he read the news, Legere's wide smile failed him. Next came a text: Would he speak on CBC's Mainstreet that afternoon? "Yes," he thumbed back.

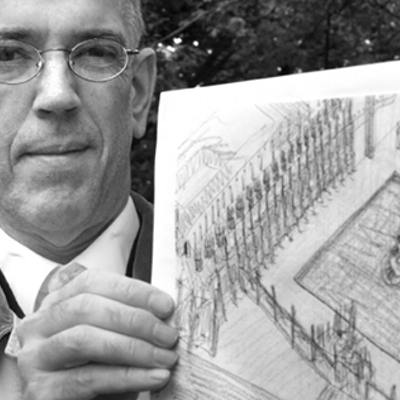

Twenty years after he created it, Ken Pinto announced his intent to put the Atlantic Fringe Festival on pause for two years. He hadn't planned to tell the Herald reporter, but communication had never been his forte.

After years of struggling to raise Fringe, Pinto had a new baby. Titanic 100 was a festive wake to commemorate the disaster that killed 1,523 people. "She's a metaphor for so much of life's situations," the Titanic 100 pamphlet mused. "In fact, she's a metaphor for life itself. We all hit the iceberg...really." Pinto had taken on too much, but the irony of the situation was lost in the kerfuffle.

"It seemed just like a bully decision---that someone was taking their ball and going home," Legere says. "But in this case it was because he had a better game to play."

Legere's part was The Facilitator---passing the gravy at dinner. With the help of the theatre community, he organized a town hall meeting. On a dark and stormy Sunday, some 70 people filled too few chairs at the Cultural Federation of Nova Scotia. Ken Pinto smiled as he walked in and took a seat on the floor. His last five days were spent speaking to the media and, as a result, the theatre community had barely seen him. Many felt frustrated by what they saw as a unilateral decision to abandon the festival. Pinto thought the room was quite friendly.

In the middle of the agora was a large flip chart that held an agenda written up by lawyer Kevin Kindred. In less capable hands, the tension in the room could have broken into chaos, but Kindred focused on the future of Fringe rather than the fear of its demise. Everyone wanted the same thing: to bring the Fringe back in line.

Pinto had envisioned it as "a low-cost, low-risk theatre delivery system for art, artists and audiences."

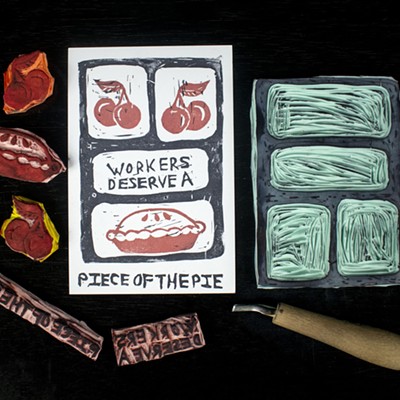

At least that was the idea 20 years ago. In 1991, fringe festivals were the "hot movement," Pinto says. The first one started in Edinburgh in 1947 and the medium spread across the Western globe. They swept Canada---first Edmonton in 1982, then cities further east and west. People wanted to see engaging alternative theatre minus the censorship and filtration that usually walk hand-in-hand with for-profit endeavours. The focus was on content above all else.

Every other Canadian city had a fringe and Pinto wanted one for Halifax. As similar festivals in New Brunswick and PEI failed, his idea became something unique to our coast. It was a platform for emerging artists, some of whom had never performed before. It was the Atlantic Film Festival, the Halifax Pop Explosion, the Nocturne of its art form.

Technicians, venues and suppliers were paid for their efforts, but the artists themselves didn't perform for the money. Instead they relied on the box office alone, minus the $1 shaved off each ticket and absorbed into the festival's bank account. They had a different expectation: a festival that could expose their art to directors, producers and an international audience. These expectations were never fully realized.

It's tough to pinpoint when Fringe lost momentum. The festival's logo had good reason to grin for the first four years, but over the next decade the annual event became increasingly isolated from the wider community. Technical and organizational concerns were voiced and unanswered. Accountability appeared unimportant to the festival's creator and sole organizer. Members of the board---unchanged and unchecked for years ---shrank into the background.

In September 2010, touring performer Mikaela Dyke wrote an open letter to Halifax's Fringe: "I certainly hope that the patrons who were left waiting outside the box office for an hour-and-a-half on Sunday past, and others who have shown up to shows only to discover that they were cancelled without any updates to the website, the 1-800 line or even signs on the door won't be upset with the artists themselves," she wrote. "We have no control over many of these variables and, in fact, pay a fee that is intended to cover things like box office and marketing."

When asked for an explanation, Pinto dismissed her concerns as unimportant.

The festival never went in the red---thousands of dollars in volunteer hours made sure of that. But for the five years leading up to that stormy day in April, audience attendance had steadily declined.

Fringe had become, in the words of Bus Stop Theatre owner Clare Waqué, "An administrative clusterfuck." The festival could not continue at its current pace. Current recognized agent for the festival Thom Fitzgerald didn't inherit any papers, documents or balance sheets---it seemed Pinto kept them all in his head.

Upstairs at The Plutonium Playhouse last Sunday night, Dr. Brown---a mime with a knack for showing balls---had his audience roaring with laughter. Fitzgerald said it was the show that epitomized this year's festival: fun and engaging. It ran smoothly with no visible technical error, no scheduling mishaps and no long waits.

Fringe isn't yet perfect, but a show like Dr. Brown Becaves demonstrates the festival's potential---a full house of engaged patrons, an enriching experience, a professional launch pad for art and a comfortable hostel for touring performers. Once the festival realizes that potential, it can bring the content back in line with its audience. It's not an empty promise anymore.

This year Fitzgerald made first contact with the Edinburgh Fringe. He organized the first advance box office, which sold over $3,000 worth of tickets before opening night. The theatre community hired a mostly new, active board of directors, including Pinto. The community will also hold another town hall meeting to facilitate feedback.

"It's a classic, classic phrase that you don't know what you've got till it's gone," Fitzgerald says. "And, you know, I think after 20 years, Ken was entitled to want to relax and hand it over. Sometimes I wonder if this wasn't his plan all along. Maybe he wanted to see if the community would step forward and own it."