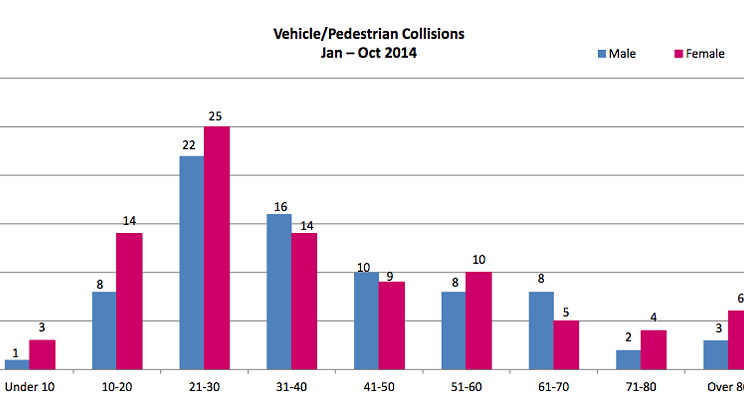

When Halifax police released their latest annual report on pedestrian and vehicle collisions last month, the headlines focused on one number: the 55 percent jump in accidents since last year. Whether or not you consider that 55 percent increase a frightening trend, or simply attribute it to more reports being made by frightened pedestrians, ultimately it’s not the number we should focus on.

The most important number in the 2014 pedestrian collision stats is four, because that’s the number of people who were accidentally killed while walking on Halifax’s streets. The next most important is 39, the number of people moderately-to-seriously injured while walking, also by accident.

The lion’s share of the discussion around these accidents has been about who’s at fault—generally either the pedestrian or the driver. But a growing number of voices are looking beyond the human factor, and asking what we can do to design our cities to be safer for walking. With that in mind, The Coast presents an introductory guide to making Halifax pedestrian-friendly.

We need a walkers’ advocacy group

Bill Campbell started getting interested in walkable neighbourhoods after participating in a pop-up park at Queen and Morris during the 100 in 1 Day festival last summer. These days, he’s working on the formation of Walk Halifax, a new citizens’ advocacy group for the needs of pedestrians.

“The big picture is every pedestrian route is safe, comfortable and interesting,” says Campbell. The group has yet to have its first formation meeting, scheduled for March. “There’s this vast amount of real estate that lies between buildings—the street and the sidewalk. There has to be more attention to the needs of the pedestrian in that public realm.” Walk Halifax will work with municipal and provincial bureaucrats and politicians to “put a pedestrian lens” on their work. “When they’re building something, looking at a regulation, changing a law, or reviewing something, I just don’t think that’s in the forefront of their minds right now,” says Campbell.

Once formed, Walk Halifax will fill a gaping hole in transportation advocacy in the city, taking a seat alongside groups like It’s More Than Buses, and the Halifax Cycling Coalition.

Move over, cars: make room for pedestrians

It’s been a rough year for walking on city sidewalks. First, a busy construction season in the summer and fall closed off a staggering number of downtown main streets. Now, icy conditions make many paths virtually non-passable.

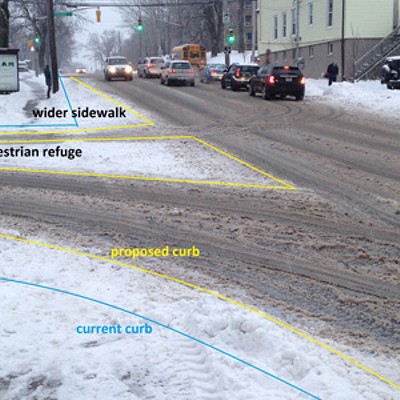

If you’ve driven down Quinpool Road lately you may have noticed that the street has lost a couple feet on either side to snowbanks, but still manages to accommodate the same number of traffic lanes.

“There’s so much excess road width in the city,” says Halifax’s first (and former) chief urban designer, Andy Fillmore. And we may need to transfer some of that space over to sidewalks, particularly on our busiest corridors. “The busier the street, the more sidewalk you should have,” says Fillmore.

Fillmore isn’t alone in his opinions. Mark Nener is a community planner with the Dalhousie-affiliated Cities and Environment Unit. He offer up Spring Garden Road as an example of a sidewalk space in desperate need of widening and redesign. The street “just needs more space,” says Nener, “and a better-quality pedestrian environment.” He’s a fan of the space surrounding the new Central Library. “There’s a precedent there for quality of infrastructure.”

Several years ago there was a plan to realign sidewalks on Spring Garden, moving some loading and parking off the main drag. “The merchants actually rebelled against it,” says Fillmore. “In the end, council lost confidence that it was what the community wanted. And unfortunately the money was diverted elsewhere.”

Nener has hope now for Argyle Street, which has a 2012 streetscape plan (spearheaded by the Downtown Halifax Business Commission) calling for limited car access and much more pedestrian space on the patio-laden street. When convention centre construction wraps up, says Nener, there will “a huge opportunity to implement that plan.”

Of course, years ago business owners put the kibosh on a pilot project in a similar vein, proposing to close Argyle to vehicles on Friday nights and weekends. “It came undone about one minute before it was about to happen,” says Fillmore, “because of one of the businesses on the street determined it would be detrimental.” The city, says Fillmore, chose to put the concerns of business owners ahead of the general good. “It’s just an indication that we haven’t embraced a progressive philosophy yet. We’re still sort of thinking about this in old-fashioned terms.”

Create a hierarchy of modes

This is actually less about creating a hierarchy than about turning the current hierarchy on its head. Since World War II, North American cities have been built for cars, and Halifax is no different. But these days, some cities are choosing to do it differently.

Andy Fillmore points to the Vancouver example. According to its 2012 transportation plan, Vancouver’s transportation decisions all reflect a “hierarchy of modes” with walking at the top of the list, followed by cycling, transit, taxi/commercial transit/shared vehicles and lastly, private automobiles.

“That philosophy is important,” says Fillmore, “because that starts to guide you in concrete decision-making around infrastructure.” When Vancouver’s technocrats are considering “whether to widen the road or what the radius of the turn should be,” says Fillmore, “they say, ‘OK, first, what’s best for pedestrians?’”

In Halifax, on the other hand, we work under a regional plan with underlying assumptions that prioritize the convenience of vehicle traffic. “There’s this assumption that we’re not willing to accommodate any increased congestion,” says Mark Nener.

“If an intersection treatment for bikes or pedestrians proposes the removal of a right-turn lane,” he says, “and the traffic and right-of-way people decide that the decrease in vehicle capacity is unacceptable, then they will not allow that treatment.”

One pedestrian death is too many

It’s all the rage among North American cities lately: Vision Zero. Originating in Sweden, where it’s national policy and a way of life, Vision Zero aims to completely eliminate deaths and serious injuries caused by traffic accidents.

As a goal, it’s radical, especially in a world dominated by the cost-benefit analysis, where four tragic deaths in a Halifax year can get rationalized as the cost of modern life. But there’s more to Vision Zero than zero.

Vision Zero expands the responsibility for these collisions beyond the walkers and drivers directly involved, to include the regulators and designers of our roadways and sidewalks. And it shifts the focus away from all accidents to those that hurt or kill us (or those where we hurt or kill others).

Seen through the lens of Vision Zero, Halifax’s biggest problem is not the 269 pedestrian-car collisions that were reported last year. Instead, it’s the four deaths and 39 moderate-to-serious injuries that resulted from those accidents. Vision Zero recognizes human error as inevitable, and so aims not only to reduce the chances of accidents in general, but also limit the damage they can do.

Mark more crosswalks, and mark them properly

We all know (don’t we?) that every intersection is a legal pedestrian crosswalk. Or actually, four of them. But we forget this because very few of them are actually marked.

Downtown councillor Waye Mason is campaigning now for zebra stripes across Quinpool at Monastery Lane. He’d also like to see markings across Sackville Street at the pedestrian-heavy Argyle, and a doubling up of stripes across Barrington at George. His pet peeves about “Halifax’s traffic orthodoxy” include the propensity to only paint stripes on one side of an intersection.

“Tourists are forever coming up George Street and crossing into Parade Square,” says Mason, “and we only have a crosswalk on the south side of George. The traffic engineers are trying to force the behaviour of the pedestrian to not cross on both sides, but people cross anyway because they know it’s a crosswalk even though it’s unmarked.”

Halifax’s take on crosswalk markings seems to be that their power to stop cars somehow depends on their scarcity. “To over-saturate the streets with crosswalk markings would reduce their significance greatly,” says Halifax’s traffic and right-of-way services website.

The argument for more crosswalk markings is, of course, the opposite. Mason notes than an early draft of HRM By Design asked for zebra-striping in all downtown intersections, to mark downtown as a pedestrian-focused place. But the traffic authority of the day said no.

According to Halifax’s policy, fast traffic can actually work against the possibility of getting a crosswalk marked, because “pedestrian safety may be compromised.” Presumably that’s because markings encourage more pedestrians to cross.

Norm Collins is Halifax’s most vocal pedestrian safety advocate. He became known for the crosswalk flags he set up along Waverley Road, where traffic moves fast and there are no sidewalks but people still need to cross the street. Collins is a proponent of better markings on crosswalks (he likes the idea of reflective tape on crosswalk poles, because of the visibility bang for the buck) and also of more marked crosswalks.

Collins says he’s often reminded by his wife that “the vast majority don’t understand that’s a crosswalk, and that I have a legal right to cross and they have a legal obligation to yield.

“And I kind of accept that. But I say, if you’re going to take away the unmarked crosswalks as being legal, in exchange I would expect there to be a marked crosswalk, say, every 300 metres. So you’d never have to walk more than 150 metres in either direction to cross the street.”

By way of example Collins offers up Baker Drive in Dartmouth, which features a two-kilometre stretch of road without a single marked crosswalk. “It’s very busy and there’re apartments along there,” he says. “I think it’s just awful.”

Let’s slow down the speed limit

If you accept the Vision Zero-inspired attitude that we need to focus on reducing our chances of getting killed and hurt (or killing and hurting others) when accidents occur, then speed becomes a key factor in the

solution.

According to a report by the World Health Organization, pedestrians have a 90 percent chance of survival when struck by a car travelling at 30 kilometres per hour or less. But if that same car goes 45kph, the chance of survival goes down to 50 percent. And it gets worse outside the urban core, where cars go faster. Pedestrians have almost no chance of surviving an impact with a car going 80kph, according to the WHO report.

If the Nova Scotia government were to change urban speed limits, we would be the first province in Canada to do so. Though we’d have to hurry to beat Ontario, which just began consultations on the possibility.

Of course, changing the speed limit is only part of the battle when it comes to slowing cars down. Norm Collins thinks more speed humps may be necessary to actually reduce car speeds. “They are effective,” says Collins. “As a driver, I slow down.”

And a basic design factor like street width can play a role in speed. “People generally drive as fast as they feel comfortable driving,” says Mark Nener. “The wider the space the faster they go.”

“Part of the whole issue is whether the balance between drivers and pedestrians is at the right point,” says Collins. “If we’re going to make the world safer for pedestrians, and if we’re going to not accept the number of collisions and injuries, then drivers are going to have to give a little bit.”

Intersections need bigger bump-outs

The bump-out (AKA neckdown or curb extension) is an extension of the sidewalk at an intersection which is becoming a favoured improvement among new urbanists. “It makes pedestrians more visible,” says Bill Campbell. “It tends to slow traffic at intersections. It shortens the distance the pedestrian has to cross, and provides safe refuge.” Bump outs also have the benefit of letting pedestrians see past parked cars and snowbanks, without stepping out into traffic. For clues as to where bump-outs might work, check out the sneckdowns in your neighbourhood. Coined by New York videographer Clarence Eckerson when he noticed the many “snowy neckdowns” created every winter, Halifax sneckdowns are being documented by Blair Barrington at sneckdownhalifax.tumblr.com.

Burn the books on roadway standards

There’s a tectonic shift happening in the city building professions, says Andy Fillmore. “For a very long period of time, the whole business was run by engineers.”

These days, more and more, it’s the planners and urban designers who are leading, he says.

However, we still rely on “volumes and volumes of land use bylaws and roadway design manuals” left over from the urban renewal period. That period, which saw the construction of the Cogswell Interchange and the razing of Africville, is what Fillmore calls “a discredited era of city-building.” These guidelines, says Fillmore, “encode that 1960s vision of the city as a machine for moving cars.”

This is perhaps why at a meeting of the Council for Canadian Urbanism, former Vancouver chief planner Larry Beasley suggested planners across the country hold a ritual burning of all roadway design guidelines.

Of course we need to build our streets and sidewalks to some sort of standard, and lo and behold, there is an alternative on the rise. The National Association of City Transportation Officials has published its Urban Street Design Guidelines. The NACTO guidelines promise “a blueprint for designing 21st century streets,” and include tools like pinchpoints and chicanes that serve to both increase public pedestrian space and reduce traffic speeds.

Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal are members of NACTO, though the group has plenty of affiliate members on a smaller scale as well. Halifax staff have yet to do a full assessment of NACTO, says spokesperson Tiffany Chase. So it seems like any ritual burnings of our current street guidelines may be a ways off.