My name is Annie Margaret Clair. I was born and raised on the reserve in Elsipogtog, New Brunswick.

My first language is Mik'maq, so English is a difficult language for me to grasp. I only started speaking English when I went to school, around age five or six. English was not spoken in my home.

I have four children—Cody, Stephane, Junior and Shanelle—and three grandkids: Hailey, Khloe, Clover. I have a huge family: my mom had 11 brothers and sisters, my dad had four sisters and seven brothers.

When I was seven years old, social services took me from my mother and moved me into a foster care home. I never knew my father growing up. My mom was an alcoholic and a single mom. My older sister—I think she was about 15 at the time—tried to take care of all of us for awhile, but eventually she got tired. She thought we'd all be better off in foster homes.

My first foster home was with a family of nine, in Elsipogtog. Back then, I didn't know who these people were or why I was there. All I knew was that I wanted to go home to my mother.

I'd play outside during the day. At night, when everyone was sleeping, I'd sneak outside and wander the woods looking for my mom. I'd sleep outside when it started to get late. I don't even know how many times I ran away from my foster homes, and I can't even remember how many foster homes I stayed in.

I was pretty as a child (I'm still pretty) and was continuously being approached by men, even men far older than me. When I was 11, I was babysitting for my foster sister's brother-in-law when he sexually abused me. He was in his 20s at the time. I was so scared and had no idea what was happening, so I kept it a secret for years.

I thought no one would believe me. I turned to drugs and alcohol, thinking they would numb the pain away.

It wasn't until I was 24 that I sought help through counselling and rehab. By that point I was already a mother of four. In grade 10, I became pregnant and eventually had to drop out of school. My dad—a man I grew up thinking was my biological father for years—disowned me.

Both my foster parents wanted me to get an abortion.

I started raising my first son in a heatless shack, near Main Street in Elsipogtog. We had no running water.

I've been in my share of abusive relationships: mentally, emotionally and physically.

I'm telling you all this not because I want your sympathy or your pity, but because I want you to know that my story, this story so far, is not uncommon across First Nations communities across Canada.

Shame is also a big part of this, and I find that the only time that these stories come out, that we really begin to speak about experiences like mine, is when alcohol and drugs come out.

I'm also telling you this because I find that Aboriginal women, any Aboriginal woman, often have our childhoods taken away from us. Our parents, our aunts, our uncles, our grandfathers and grandmothers, were abused by residential schools. And that cycle continues into our own communities now, at this present time.

Statistics show that we are far more likely to be the victims of violent crime, to go missing, to wind up murdered.

I've seen people go missing and get murdered around me, without even looking for it.

I moved to Neguac, New Brunswick, in March, 2009, to be closer to my two boys, who I hadn't seen in years. Neguac is the Acadian community about a five-minute drive from Esjenoopetitj (Burnt Church) First Nation, on the shores of the Miramichi and the Northumberland Strait.

I knew Burnt Church well, because of close friends and family in the area. I had also lived there for a period in the 1990s. I knew Pam—Augustine at that time, now Fillier—and Boyd Bonnell well and I still consider them friends.

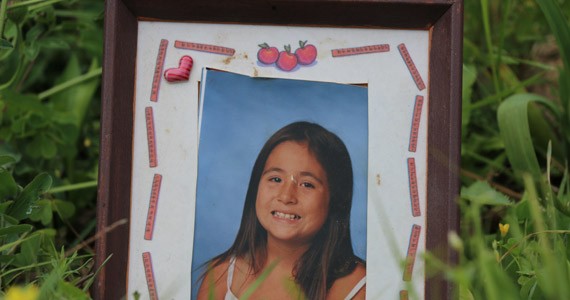

They were Hilary Bonnell's parents. She was their only daughter.

On September 5, 2009, 16-year-old Hilary went missing. When I first found out that Hilary was missing, my friends mentioned that there were volunteers gathering at the fire station to start searching the Burnt Church area for her.

Volunteer coordinators arranged us into tight rows. We were made to walk into the back woods behind the Burnt Church community store, 4D's. We had to keep our eyes open for any sign of her or her belongings, like shoes or clothes. This general vicinity was the last place she had been seen a few mornings earlier, and we searched for two months.

We walked those woods, wet and swampy with the coming fall, in rubber boots and reflective vests.

We divided the woods into quadrants and searched.

And walked and walked.

We lit a sacred fire for Hilary behind the Burnt Church fire station as we searched. People would go there for their prayers. While she stayed missing, accusations went around the community.

I heard all kinds of these different stories. But the community still had hope, that Hilary was still alive and that she was being kept somewhere. At times people even thought that she had just hiked somewhere.

When I close my eyes, I can still see Curtis Bonnell's house and trailer, two houses down from 4D's. One time I'd almost rented the trailer, but I remember driving into the front driveway, checking it out, and it just not feeling right.

Curtis Bonnell, Hilary's first cousin, would later be convicted of murdering her, smothering her with his hand after he raped her on the ground. (Curtis buried his cousin near the Tabisuntac area.) To get there he would have had to have driven past my house in Neguac.

Interview with Hilary Bonnell's mother, Pam Fillier

"She had called me the morning she was murdered," says Pam Fillier, Hilary's mom and my longtime friend. "She called me at three in the morning. And I could tell, you know, most teenagers at that time are getting into a little bit of booze. I said 'Hilary, you go home. Go over to Auntie Sherrie's.'"

At the time, Pam was staying in Miramichi, about 60 kilometres to the south. Hilary was visiting family and friends for the weekend in Burnt Church.

"We ended our conversation. I said, 'I love you,' she said, 'I love you too.' And we hung up. And I never heard from her again."

Pam tells me about coming down to Burnt Church to search for her missing daughter. She tells me she knew something was wrong, that this might not end well. There were also coincidences, things that Pam did the morning her daughter was murdered, like driving through Tabisuntac.

"That day that he killed her, I never went for a drive in Tabisuntac in so many years I couldn't tell you how long ago it was," says Pam. "Just something that day, I wanted to go. And I kept telling Fred, 'Come on, let's go for a drive to Tabu,' not even knowing the reason I was being pulled there was because Curtis murdered my little girl. And that's where she was put."

Pam says the New Brunswick RCMP were slow to react, that initially they didn't even get back to her. They took her statement and she didn't hear from them again. That police on the phone just gave her the runaround, like her daughter wasn't important.

"I would call the police department and ask them 'Is there any news...what have you guys been doing to find Hilary?'" says Pam. "That officer would say 'Oh no, you've got to talk to him.' Then when I'd talk to him, he'd say 'Oh no, this guy is handling it.' It was like they were playing hot potato.

"Finally I got sick of it. And I'm not a stupid woman. I called the media right away. Because I knew, if I call the media, it's gonna humiliate them, and it's gonna force them to do their job. Instead of just thinking she's just another Indian girl getting drunk, out partying and didn't go home."

Curtis, Hilary's murderer, was initially part of the search parties looking for her. He acted as though he didn't know he had murdered her and buried her. "You know that Curtis would even be there, when they all went to, I think Portage River?" says Pam. Portage River, far from where Curtis had buried Hilary, would have been a wild goose chase. "He was even there pretending to look for Hilary."

When the police began to track him down, his stories related to Hilary's murder changed several times. Pam remembers his behaviour on the stand, at his trial.

"In court, he was looking at pictures of Hilary. It was pictures of her dead body that he's looking at. Such a friggin' monster, [he] puts his head up and he's still able to smile and talk," says Pam. "I was so disgusted. I said, 'Look at him. Looking at pictures of my little girl's dead body and putting his head up and smiling.'

"That's a monster. And it made me cry of course. You know, treating my kid like that's a dog they just ran over on the road."

To me, it seems like we native women just get treated like a piece of furniture. You know, you sit on furniture, some people just sit down, spill something on it, they don't care? Like dirt, like, "Who gives a damn? We can smoke on it, we can drink on it, we can piss on it."

I feel like we're not honoured or respected. That we should be treated like fine antique china, like so precious, the way people get: "Oh no, you can break it, you can't dirty it."

But fine china gets treated better than a native woman.

Bonnell's murder made me scared for my own daughter, who was 13 at the time. I became overly protective; if it could happen to Hilary, it could happen to her too. I made it a rule that she couldn't go anywhere without her brothers.

I met Loretta Saunders on the afternoon of February 11, 2014. She picked my daughter and I up from an appointment and drove us to a restaurant near the Victoria General hospital in Halifax, a city I had moved to only days earlier.

Saunders, attending Saint Mary's University in town, wanted to interview me about being Mi'kmaw—my culture, language and traditions.

She stood out to me as having a happy spirit. She told me she knew how it felt to not know anybody in a new town and that she would be my daughter's friend, and that they could start hanging out together, and that the age difference between my teenage daughter and herself was not important.

I felt like I knew her as we spoke that first time, and when we parted ways we were already friends.

I never saw her again.

Through social media, on the 13th, I learned that someone named Loretta had gone missing in Halifax. Initially, I didn't know it was her. I didn't recognize the picture—maybe I didn't want to—that was now circulating around the internet. I had to take my laptop and show my daughter. Even when she repeatedly told me it was Loretta—our new friend—I disagreed.

We were both in shock. I had texted her the day before, asking when we would next get together—and had received no reply.

At the time I thought she was just busy with school.

We went to the Mi'kmaq Friendship Centre on Gottingen Street. There was action everywhere—go, go, go—as folks broke up the important tasks of looking for Loretta amongst themselves.

Loretta's brothers arrived days later from Labrador. They just wanted to find her and take her back home and in the meantime have a private place to be—to be safe, away from media. There were so many cameras and microphones everywhere and they just wanted their space to do what they came to do—to find their sister. Their mother had told them to come to Halifax, to find Loretta and to bring her back home, however it needed to be done.

One brother wanted to search the woods of New Brunswick, where Loretta was eventually found.

When I think back on it, there were similarities, in the feelings and the actions of those involved, between Hilary going missing and searching for Loretta. Right away you think:

I wonder what happened to her?

I wonder who took her?

And in both cases it was just people they knew. It could be your neighbour, your uncle, your cousin. And that's the most devastating thing.

It was people you trusted.

I talk to Loretta's mom, Miriam, over the phone. She and the Saunders family are back in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador.

"She was a quiet girl. She got along with everybody. Happy. She did anything for anybody. Smart," says Miriam. "She was a very petite little girl. She was always daddy's and mummy's girl. And she enjoyed swimming, skating, things like that. She was a well-behaved little girl, you know?

"She was a real smart girl. She did her upgrading. In eight months she finished these programs that would have taken three years. She did it in eight months. Then she went to university. She was doing good. She was an honour student. Getting As."

Interview with Loretta Saunders' mother, Miriam Saunders

When Loretta went missing, nobody told Miriam. It was February 17, four days after I'd heard on social media, when the Halifax police announced that she was missing. Miriam tells me that the police advised her to stay home, that they were getting close, that it would be better for her to stay put.

I ask her how she felt, waiting at home.

"I was thinking. Wondering who had her. Whoever had her, what they were doing to her. I couldn't sleep. I couldn't eat. I was by the phone, day and night. Waiting to hear from her. Phoning her phone."

In Mi'kmaw tradition, where people die, that's where their spirit is at. It doesn't stay there forever. Just a little bit. Until a year goes by, and that's when they start their journey. But the spirit doesn't go there right away. There's levels, and the spirit has things to do before it keeps going.

Like Hilary Bonnell, she will be helping the spirits of women who go through this. She'll be there to help them. To lead them. So when the time comes, for Loretta, Hilary will be there to help her and to meet her. The same thing will happen; Loretta will do the same thing.

It's like earning, or gaining, your wings. Slowly you're getting to that spirit world.

There's something else.

Loretta was pregnant. One month. When I saw her, I knew, immediately. She was talking about craving chocolate, and I told her: "You're pregnant."

She knew. She found out in January.

"We was right excited," says Miriam. "I was all excited because she was gonna have another little 'princey.' She was going to take one year off of school. And when the baby was a year old she was going to get me to quit my job and take care of the baby with her. And I was going to. I was going to go quit my job and take care of her baby while she went and finished law school.

"That baby was going to be a human that we were making plans for. The baby that she was carrying is not recognized. That was another life. But it's not recognized. My grandchild isn't recognized as a human in my daughter's body. And we had plans to take care of it."

Miriam tells me that it was Loretta's pale complexion—the police first identified her as a "white woman missing"—that made her daughter's murder a national headline.

"When they first had her down: White Woman Missing, I was right happy," says Miriam. "Then they changed it, down lower. Then they finally had it: Native Woman. I was right worried. Because when she was white, they'd look harder, and they talked more to me. After that they never called me once. I had to call them to see what was going on with my daughter's case.

If Loretta had looked more "native," says Miriam, "they wouldn't have been so persistent and insistent on everything. That's the way I feel, personally. I was just scared that's how it would have been."

When I think about it, I wouldn't want to be less important than anyone else in this world, because of my colour. Because if anything were to happen to me, I would want them to find me, no matter what colour I was, what culture I was. Because I have a right like everybody else does. And I should be treated as an equal. I'm human like everybody else. I might have a different skin colour. I might speak a different language.

But all our blood is alike. We all have red blood.

Our native men also go missing. This needs to get put out there too—our men are just as important as our women. We don't just have daughters. We have sons too. And boys can go through the same thing, and their mothers can feel the same pain and loss.

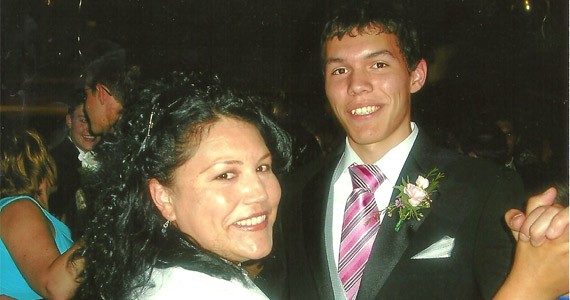

At age 20, on November 25, 2012, Chris Metallic went missing from the town of Sackville, New Brunswick, where he was studying third-year anthropology at Mount Allison University. Chris went at a party and never came home.

"He left his cell phone at the party. His shoes. His glasses," says Mandy Metallic, Chris' mom. "Everyone thought he was going. For some reason he wound up going the opposite way."

Chris' tracks led away from the direction towards his house, which would have only been about a "15- to 20-minute walk" from the house party. Despite search parties that have now gone on for two years, the trail has gone cold.

"He was quiet. He never got in trouble with the law. He had so many friends," says Mandy of her son. "He loved his sports, especially basketball. They were always winning championships. He worked with children at the youth centre [in Restigouche First Nation, Quebec]. He had a lot going for him. He had his own hopes and dreams. And I don't understand why, what happened. We all had good relationships. A lot of people looked up to him."

Chris has never been found, so Mandy doesn't have that same closure as Miriam and Pam, who know their daughters have been murdered, and that they're gone. For Mandy, I think that she's not going to stop. That she'll keep looking, because she's bound to find her son. As a mom, it's hard to think that your child is dead, and in your heart they're still alive.

Interview with Chris Metallic's mother, Mandy Metallic

"I'm going through daily torture, of not knowing," says Mandy. "Where he went. What happened to him. Where he is right now. If we're ever going to find him.

"I still have hope. But it doesn't look good. And he wouldn't do this to us. And I always told him: 'It doesn't matter if you're an adult now. If you're going to go somewheres out of town, you let us know.' And he always did."

If my son went missing, I'd never stop looking. It's hard to let go of a son, because they still had a long life to live. His life never really actually started yet. It was just starting to start.

All of them, all these young kids. They all had futures ahead of them. But that is all taken away. And it just breaks a family into pieces. To see that their children are gone. That they won't get to see them get married. To have children. To have grandchildren.

As parents we always have hope in our children. No matter what happens. And that we never give up. When we have our children, the world feels like a peaceful place. When we lose them, that all breaks. Because that piece is missing in our hearts.

"We were all happy, before this," says Mandy. "Sometimes I think that this is going to tear us all apart. But we're all sticking together.

"I didn't put [Chris] on the government website for missing people yet," says Mandy. "Only the police can authorize that, and they waiting for me to give the OK, and I'm just not ready yet. I don't want him to be part of all these missing people. I don't want him to be a statistic. I just want to find him and I don't know how we're going to move on after this. I'm scared we're never going to find him."

The epidemic of missing and murdered aboriginal people is an important topic that needs to be heard and seen for other to understand how this effects everyone, especially the mothers and families. Let us honour the memory of Loretta Saunders, Hilary Bonnell, Chris Metallic and many other aboriginal women and men who are gone.

This is Annie Clair's first piece of journalism.