The Coast has long argued that the police department was overly restrictive with its release of information (for example, see this article from 2009, and this blog post from 2011). The police blotter has long been public record in every American city, but not in any city north of the border. There has been no legal reason for the cross-border difference but rather what appears to be a cultural sensibility: Canadians seem much more willing than their southern neighbours to trust government, and there hasn't been a strong a tradition of a watchdog press north of the border, demanding public access.

Why should the police blotter be public record? To give just one example of the kinds of problems that can result from a restricted flow of information, consider the series of swarmings around the Halifax Common in the summer of 2010. For whatever reason, the police department decided not to publicly report any of the swarmings, even though several of them resulted in victims so badly harmed they had to be hospitalized. Throughout, the public knew of no increased danger, and kept walking near the Common. And more people were hospitalized. Police silence may well have put people in the hospital. (The department subsequently apologized for not making the swarmings part of the public record.)

Two years ago the police department told The Coast it was working to address our concerns. It's been a long two years, but finally the department has responded wonderfully. Earlier this year it started a crime mapping website, which is still a bit clunky—it doesn't map all calls, there's no indication of how the calls were resolved and the information drops off the map after seven days. But now comes the full police blotter, which once integrated with the map, should solve those problems.

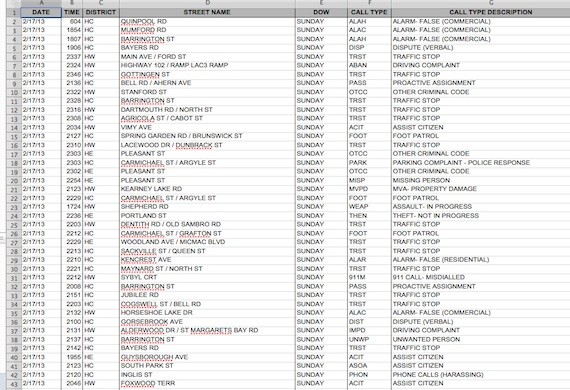

Last week, the department sent us a sort of beta version of the blotter, which looked like this:

(See the entire document here).When we first saw this, our first thought was this is good, but it's only about two-thirds of the way there: still missing is the police officer's narrative, saying what happened and what the result of the call was—was anyone arrested or charged, for example. But police spokesperson Theresa Rath assures us that the officer's narrative will be included in the blotter, albeit there may be some delay, as the officers will have to be trained to do so. (Already the officers write an incident report for each call; the narrative for the blotter will be a parred down version of that.)

The plan is that twice each day, the blotter will be made public, attached to the regular shift sergeant's media release.

This is everything we asked for.

There are a few caveats, however. First is the quality of the officer's narrative: the officers must be instructed that the intent is to inform, not to obfuscate. There is no doubt that from time to time the blotter will describe some boneheaded mistake on an officer's part, or that some potentially bad guy was able to outrun a cop, or other less-than-flattering revelation about the department. Cops are human, so of course such events happen. The department will do better to own up to them, rather than try to hide them.

Second is that with full reporting, mistakes are bound to creep into the blotter. Again, cops are human, and make mistakes like everyone else. This past weekend, for example, two women were stabbed on Gottingen Street. The police release placed the incident in the 2000 block of Gottingen, between Cogswell and Cornwallis Streets, the block Theatre Lofts is on. In reality, however, the stabbings took place in the 2300 block of Gottingen, in Ahern Manor. Alerted of the mistake, the department quickly issued a correction. (Strangely, that same mistake has occurred in the past.) But if not caught, these kind of mistakes could have immediate implications (what if you read the release and had relatives living in Theatre Lofts?) and, long-term, could skew the data. There should be some easy way for the public to notify the department when mistakes creep into the blotter.

More substantially, the blotter will list all police calls, but not all police operations. We think it should be easy to get all the officers' reports into the blotter, for instance when an officer isn't responding to a call, but instead comes across an incident simply in the normal course of patrolling. More problematic will be recording arrests related to investigations—last weeks bust of the Compassionate Use club, for example, never made a media release, and wouldn't have been recorded in the blotter, either. This is a problem.

Some readers have questioned us about the need for the blotter. One objection is that the details of police operations are "none of our business." But surely, when the police can act secretly, we don't live in a democratic nation. How can we have democratic control of our police if they public doesn't know what the police are doing? The public needs to be able to assess risks to public safety, and police responses to those risks, in order to decide how best to allocate limited resources.

A better objection was raised by a student, who suggested that with full information on all calls, it's more likely that some neighbourhoods will be stigmatized as "bad areas," and so people will avoid those areas, making them even less safe.

There are two responses to that concern. The first is perhaps flippant: The truth is the truth. If there's a lot of crime in a certain area, why should we be hiding that fact?

But our second response is more nuanced. And that's that besides simply regurgitating the police blotter, the media has a responsibility to provide context. Probably, if you look at crime rates per neighbourhood, you'd find that urban areas are more "dangerous" than suburban areas. But if you look at the same crime rates per capita, you'd find just the opposite: the suburbs are dangerous, because compared to the inner city, not so many people live there. Which is "true"? Well, both. And neither. With full release of information needs to come a smarter, broader conversation around crime.

Incidentally, here's what we think will happen after the blotter becomes public. First, there will be huge interest, and people will be amazed at how many police calls there are, and how much crime previously went unreported.

But then something interesting will happen: people will get smarter about it. They'll see that the vast majority of police calls are not about particularly dangerous situations, at least, not dangerous to the general public. In short order, people's general sense of the amount of crime out there will decrease, not increase.

And good reporters will start recognizing and reporting on trends. Someone will see all the calls involving, for example, potentially suicidal people, and do an investigative series on it. The public will have a better insight into that problem, perhaps so much so that different strategies for addressing the issue are implemented. Another reporter might discover a cluster of break-ins that the police missed, and write about that so that people can better secure their homes. And so on. We'll become a better informed society, making better decisions.

Another concern brought to our attention involved the reporting of domestic assault, which some readers thought should remain out of the public realm. Specifically, a couple of readers thought the location of such assaults should not be made public, as it stigmatizes the victim.

But certainly the victim's neighbours hear the screams of the victim, have probably heard such screams many times before, and have seen the police cars come again and again to the same neighbour's house. And, there is a degree of protection in the blotter reports: exact addresses aren't given, but rather block numbers. It's hard to see the downside of better reporting: the public sees just how often police are dispatched on domestic dispute calls.

One thing we can learn through more complete police reporting is that the vast bulk of police calls involve borderline social work. Public understanding of this fact will go a long way to improving relations with police, and also, hopefully, of finding better ways of addressing some of these problems.