This is true, and we know it happened. The question, however, is How often did it happen? Often enough that it could’ve affected the outcome of a close council race, like the District 3 contest, where Bill Karsten defeated Jackie Barkhouse by just 66 votes?

If dropped E-votes happened often enough, there would be statistical evidence for it in the election results. Specifically, we could look at the 2008 election, in which this particular dropped vote problem was not an issue (for technical reasons I won’t explain here), to the 2012 election, where it possibly was an issue. The dropped votes would be people who voted for mayor but not school board, so if there were lots of dropped votes in 2012, we could expect the ratio of E-vote ballots for school board compared to E-vote ballots for mayor to have risen significantly between the two elections.

I have good news and, well, possibly bad news.

The good news is that the dropped E-vote issue doesn’t show itself in the noise of the statistics, so is probably not a significant issue, albeit more investigation is needed to be sure of that.

The (possibly) bad news is my analysis discovered an entirely different issue I hadn’t even thought of: turns out, compared to traditional voting, voting electronically makes it far less likely a voter will vote for school board.

Now, with any analysis of voting, there are lots and lots of complicating factors: there are different candidates and issues from election to election, the weather might be different, some elections have uncontested candidates, and on and on. But for this analysis, none of that matters: The numbers are so glaringly large that it’s plainly obvious that many people who voted at a traditional polling station in 2008 were very likely to cast a ballot for school board, but those very same people, if they voted electronically in 2012, were very likely NOT to cast a ballot for school board.

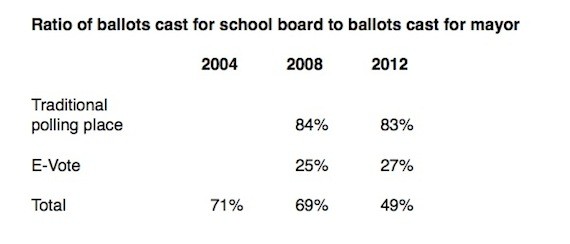

Using election results found on the city's website, I created the chart below. The “ratio” is the number of ballots cast for school board compared to the number of ballots cast for mayor. It’s possible that some people would vote for school board and not for mayor, but the reverse scenario is much more likely. I should note that this year two out of eight school board seats were acclaimed, but that didn’t affect the ratio at all, as compared to 2008, and I don’t have an explanation for that. For comparison's sake, I also show the 2004 election in the table.

The reason why the total ratio plummeted between 2008 and 2012 is that more people were E-voting. In 2008 E-voting accounted for 24 percent of ballots cast, while in 2012 E-voting accounted for 60 percent of ballots cast.

I keep considering the two acclaimed seats. If we weight the total number of ballots cast for school board to account for the “missing” votes from the two school board seats for which no one cast ballots—that is, if we increase the total by 25 percent—we get a total 2012 ratio of 62 percent. That's still a downward trend, just not as significant as the unweighted total.

But such weighting still doesn't explain the dramatic differences between the traditional and E-voting ratios. It appears some other factor increased the relative interest in school board races this year, but people who voted traditionally were still much more likely to vote for school board than were those who voted electronically.

If you vote in person, there's about an 85 percent likelihood that you'll cast a ballot for school board, while if you vote electronically, there's just a 25 percent likelihood that you'll cast a ballot for school board. And, that result has kept steady across two elections.

One possible explanation is provided by my boss, who says that when going to the traditional poll he was asked directly by a poll worker if he wanted a school board ballot. In comparison, the electronic voting process gives voters a simple way to opt out without involving a living person. Perhaps there’s a social dimension to this: it’s really hard to say “no” when the nice, but possibly judgemental, poll worker asks if you want to vote for school board, but really easy to skip the school board ballot when you’re dealing with a faceless machine.

Does this matter? I think it does, but I’m not sure in which direction it matters. There was a lot of “get out the vote” talk during the last election, with no consideration of how interested or informed the voter might be. Maybe there’s something to that, and the drop in school board voting is a very bad thing. But then again, maybe it’s better that people who really don’t care about the school board not vote for it.

Regardless, we should understand that something very significant is happening through our move to electronic voting, and figure out if this is a good or a bad thing.