On May 10, a beautiful Wednesday morning, members of the Canadian Union of Public Employees went on strike. The bulk of the striking workers are educational program assistants, but this strike includes all of the support staff for Halifax Regional Centre for Education schools. These EPAs are people—mostly women—who make sure children with disabilities, or children who otherwise need help, get an education in Nova Scotia.

EPAs are on strike for a lot of reasons. But, to hear the governing Tories tell it, the EPAs only had three requests, and the province has met them all. According to the provincial government, all the EPAs wanted were the following three things:

- Wage parity, so that every EPA in the province makes a similar amount

- Common table, so that all eight local union branches in the province can negotiate together

- Unified contract date, so that all eight locals have the same dates on their contracts

The Nova Scotia government has either missed the mark or is being deliberately misleading on what the striking workers are asking for. Because, while the government may believe this strike is about geographic parity, the EPAs on the picket line believe it’s about being treated with dignity and respect.

Amanda is a parent affected by the strike, and one of the ways she learned it was going to happen was from an instructor at her daughter’s after-school Boys and Girls Club. That instructor is also an EPA. Since EPA salaries cap out at just over $37,000 a year, all of the EPAs who The Coast spoke to on the picket line have an extra job—or two.

Amanda is not an EPA, even though she has all of the training and experience required. Being an EPA is often a violent and thankless task done for poverty wages. Amanda decided on a job working with children that was just as rewarding, but has better pay and hours.

“I put my kids before my job. I put my kids first for everything,” says Amanda over the phone. “I'm not a perfect person. But there is one thing that I strive for, and that is to be a good mom.” It’s why Amanda was devastated to be escorted off the grounds of her daughter’s school by police on the first day of the strike.

Amanda’s daughter, who has Type 1 diabetes, is literally kept alive at school by EPAs. Having diabetes means your body can’t regulate its insulin because your body has decided to try and evict the pancreas. If a body can’t effectively regulate insulin, there will either be too much or too little insulin; both cause the human body to shut down, leading to death. In order to prevent her daughter’s death, Amanda and the school board have a diabetes management plan that’s administered by EPAs.

But when the EPAs go on strike, who keeps diabetic children safe?

The job of planning for her daughter’s safety in school is one Amanda is uniquely qualified to do. The school—Admiral Westphal—has asked Amanda to be a chaperone due to her training, experience and clean background checks, so it’s normally OK for Amanada to be there. She’s been managing her daughter’s diabetes ever since her daughter was two years old.

Amanda first learned of the possibility of a strike a few weeks before from school staff, “who called me to let me know if there was a strike [my daughter] wouldn’t be allowed in school” because an EPA wouldn’t be there to monitor her insulin. This was the first time Amanda learned the strike might affect her daughter’s attendance. That’s when she came up with the initial plan to keep her daughter safe. She was told she wouldn’t be allowed to follow that plan and that her daughter would have to stay home, should a strike occur. “Not once was I offered a learning plan or the option to call a supervisor to see if there was anything that could be worked out. The answer time and again was ‘no’ due to ‘safety concerns’ even though, in normal circumstances, I am the one who makes the plan [to monitor her daughter’s diabetes] for the school in the first place. I was very confused as to how they felt I would not be able to care for her.”

That strike threat came and went with no job action. So, when the current strike did happen a few weeks later, Amanda had her daughter’s care plan ready.

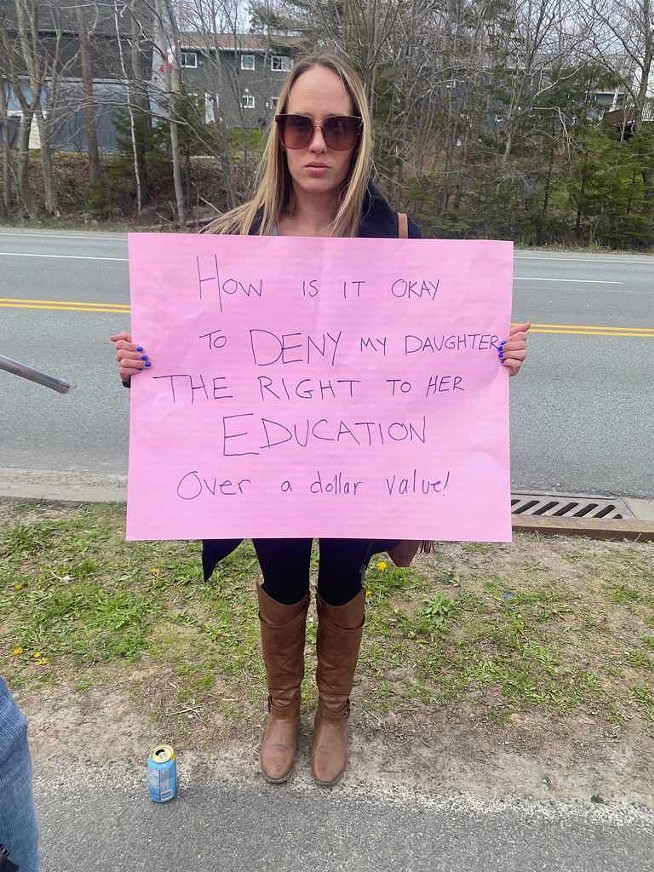

The school said no to that plan on Tuesday, May 9, the eve of the strike. “That's not really acceptable,” Amanda told the school. “You're not going to impede her education based on a political issue and a money problem that has nothing to do with her. We will be at school, I will provide her diabetes management.” Again, the school said no, threatening to have Amanda removed from school property if she showed up with her daughter—but lock the doors, don’t let anyone in and put that in a hold-and-secure; we’ll come back to that later.

Melinda’s son is 22 now, but he’s the reason she became an EPA. “They gave him the tools to be able to survive out on his own, to manage. He wouldn't have made it through to high school, he wouldn't have graduated if it wasn't for the extra help that we get in the learning center and [from] the EPAs and the extra staff,” Melinda says on the Dartmouth High picket line as cars go by honking. Melinda’s son has special needs, which is how she learned about EPAs.

Without EPAs, her son would likely be sitting in her basement, lacking many meaningful skills “because once they hit high school, social skills come in and cooking comes in and they do a lot of things to help them prepare them for life after school.” In a very real way, her son is able to live a normal life because of EPAs. “It’s amazing; I love this job,” Melinda says.

But she doesn’t love the pay. “Gross pay is usually about $27,000 to $28,000 a year. But after that, we're down to about $20,000 to $23,000 a year.” And that annual pay is 10 months of pay spread out over 12. Meaning many EPAs take home somewhere in the vicinity of $365 to $415 a week. Or, in other words, EPAs don’t make enough money to cover the cost of their housing in the HRM. Never mind other things like food, electricity or transportation costs.

That math is also why this EPA strike could go on for a very long time. Strike pay is not taxable, and since CUPE is a national union, but only Nova Scotian locals are on strike, there is very little danger of the strike fund running out. On top of that, in an act of solidarity, national CUPE members have decided to cover the health premiums for the striking local CUPE members. Pay for this strike is $300 a week, increasing to $400 in the eighth week. Meaning most EPAs are not seeing a substantial pay cut, and some of the lowest-paid EPAs—the part-timers—are functionally getting a raise and working fewer hours on the picket lines.

The EPAs were offered a wage increase of 6.5%. “It equals to about $1.43 extra an hour. And that's for the three years that we were offered the contract,” says Melinda. “We can't live like this. Most of our EPAs, we work two to three jobs just to try and survive.” Instead of spending time with her granddaughter after work, Melinda’s second job is after-school care.

The reason the PC government says this is a-OK is because it’s offered the same thing to all EPAs across the province at a unified bargaining table. This implies one of two things: Either the provincial government is made up of a bunch of idiots who don’t understand the issues EPAs are facing, or they are deliberately misleading the public by sticking to the only three talking points that don’t make them look like heartless monsters for making grandmothers work multiple, physically demanding jobs for low wages because they can’t afford to retire and spend time with their grandkids.

On behalf of the moms and dads, the caregivers and most importantly our most vulnerable kids who are struggling, it's time for this government to put their money where their mouth is. #nspoli

— Tim Houston (@TimHoustonNS) March 26, 2018

Back to Amanda. She’s on the phone with the school the night before the strike, trying to make sure her daughter could attend the next day. The school is “telling me that I literally am not allowed in the school just because I'm a parent,” recalls Amanda of that phone conversation. “I'm like, no, that's not true.”

Amanda had come up with a plan the most stringent military general would admire. Fallback plan after contingency plan to ensure her daughter stays alive. She thought she was ready, so she took her daughter to school. The principal met her at the door.

“He's like, ‘She can't be in here. You need to leave. You can't be here,’” Amanda recalls. “Stern and aggressive with his voice. ‘You're putting her in an unsafe situation. Why would you bring her here?’”

It’s important to note that the people in this story are about to, or have already, made some emotionally fuelled mistakes leading to the police escorting Amanda away from the school. It’s important to understand why Amanda and the school staff, who should have handled the situation better, made these mistakes.

Amanda’s daughter was diagnosed with diabetes at the age of two. When her daughter started school, she was expected to inject her own insulin. “The school board has decided that a child, a four-year-old or five-year-old child, is responsible to inject themselves with insulin, or their parent has to come from work or home to inject a child with insulin,” says Amanda. Lack of support for children with diabetes in schools is “why a lot of kids are on insulin pumps,” with parents shelling out the $10,000 in up-front costs to keep their kids safe under the HRCE’s liability prevention policies. Nova Scotia does cover the cost of this pump, but it’s in the form of a refund that takes 4-6 weeks to arrive. Amanda put it on her credit card, and “interest is a bitch.”

On top of that, Amanda has been waking up twice a night for the past six years to make sure her daughter's insulin levels are normal—to prevent something called Dead in Bed syndrome, the sudden, unexplained death of a young person with Type 1 diabetes. But that means Amanda has been chronically sleep-deprived for over six years.

Having lived through complications with diabetes that were exacerbated by HRCE policies that favour liability reduction over human empathy, the HRCE has taught Amanda that she has to fight for everything her daughter needs in school. It’s why she made such an extensive plan to keep her daughter safe.

The school seemed to be more concerned about HRCE’s potential liability, should anything go wrong. Just a little bit of empathy from the school in this situation could have drastically altered the course of events.

Violence in schools is an epidemic in Nova Scotia. In 2020-21, there were 11,240 physical violent incidents. “From 2013 to 2022, there were a total of 6,303 injuries reported to the WCB from education administration workers, which includes educational assistants, educational program assistants, administrative assistants, caretakers and custodians,” reported Alex Cooke of Global News in March of this year. Teachers and principals are not included in this tally of violence in schools, as they have separate insurance.

“My salary per year is $38,600. I'm top-scale because I'm a 26-year employee with the HRCE,” says Debbie Faloon, an assistive technology support worker. “I'm also a respite care worker. That's my second job, for now.” Faloon used to have a third job as a secretary at a massage clinic.

Faloon took the respite care job because, at some point in her career with the HRCE, she was an EPA. “My respite care job actually has to do with a student that I followed through his high school life,” says Faloon in the front seat of a picket captain’s car to escape the incessant honking of support from drivers passing the picket line. “He had a lot of challenges; there were a lot of issues there physically, with aggression particularly. A lot of staff were a little nervous to work with him. I took that on.”

She took the respite care job to continue helping her student as he became an adult. “I knew that a lot of people really didn't understand his way of thinking. And I knew that he is able to process everything the way we see it, he just can't express himself the way that we do,” says Faloon. “I just tried to keep guiding him on how to do that.”

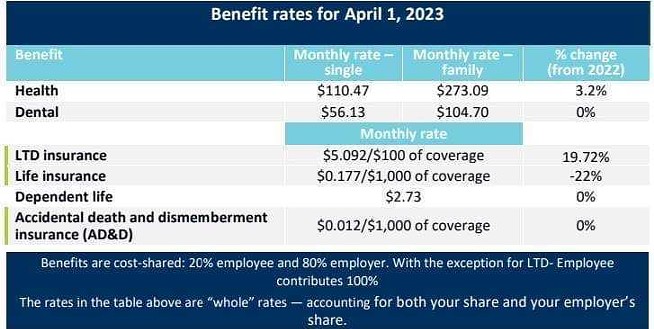

Not every EPA is able to give students the extra time Faloon did because, as she says, they’re “overworked.” On top of that, school support staff are taking a pay cut due to the violence in schools: “Our premiums have increased because of the injuries,” says Faloon brandishing a screenshot from her benefits account showing an increase in her long-term disability premium of 19% in the last year. And here’s where the math doesn’t add up: Insurance premiums, cost of living and housing costs are all way up.

Emotions were running high, and Amanda and the school administrators were talking past each other with the conversation escalating. While the confrontation was happening at the school’s entrance, Amanda told her daughter to go to class, and her daughter ran off up the stairs. The principal followed Amanda’s daughter, and Amanda followed him. When the two adults made it to her child’s classroom, she was nowhere to be found. Amanda started to panic.

To Amanda, this was yet another fight on behalf of her daughter’s education in the HRCE. “I had to fight and fight and fight this school board and the IWK,” recalls Amanda of when her daughter started school. Amanda thought her four-year-old was too young to inject her own insulin, and the IWK says and EPA is not qualified to inject insulin (and they don’t get paid enough for that anyway), which is why Amanda shelled out big money for the insulin pump. But still, her daughter needed more support from the HRCE. “She really needed someone to have eyes on her at all times as she couldn’t feel her lows at all and would just lie down sometimes,” says Amanda. Her daughter needed 100% support so that a four-year-old would not be responsible for monitoring their own blood sugar to prevent herself from slipping into unconsciousness and, potentially, dying in class.

The HRCE and IWK disagreed, telling Amanda no one got that kind of treatment. “My daughter needs 100% care and she's going to get it. You got to shuffle your people around. You got to find them in the budget. That's a ‘you guys’ problem. I'm telling you that this is the care that she needs. And this is the care she's going to get,” says Amanda of that first fight with the HRCE. When she pressed, the HRCE relented, and her daughter got the support she needed.

The morning the strike began, Amanda’s daughter never made it to the classroom. She went to hide and cry in the bathroom instead. “She was actually genuinely afraid to go into the classroom. She was afraid of her principal. She was afraid of him. Like, that's what she said. ‘He scared me. Because he was yelling, he scared me. He told me I had to get out. He said he was going to call the police.’”

Marissa Beaver is an EPA who also works as a dog groomer and dog breeder. While technically a full-time EPA, she’s only an 80% employee. She makes more per hour at her dog grooming job. And because picket shifts are only four hours long, she’s making more money on strike than when she was working.

She is not working as an EPA for the paycheck. “We definitely do it for the kids. Any progress that they make makes us feel really good inside,” says Beaver. “We try to provide the best experience for them while they're at school and teach them as much as we can. And that's what makes us thrive.”

But there is a lot of violence in HRCE schools. “We had to restrain somebody last year when I was working at a high school,” says Beaver, a small woman. “They were calling for help. And I just happened to be at the right place at the right time to help the other EPA.” Luck is what prevented the struggling EPA from becoming another insurance premium increase. Beaver trained to be a police officer in New Zealand before moving to Halifax. It’s a skillset she says is quite handy when working in HRCE schools.

Working in schools isn’t all violence—there are heartwarming stories, too. “I worked with a deaf boy last year. He and I just signed to each other. I was the only one in the school that could sign to him other than his translator. So there's violence, and then there's that.”

Low wages have another hidden cost for Beaver. “You're putting [in] a lot of love, effort. It's not only that we're teaching them, but we're giving them the hugs they need that they don't get from home.” And that’s just the school day. Then she goes to her second job grooming dogs. She has a five- and six-year-old with a bedtime of 7pm. “Then you get home and it's draining. I feel like, you know, 7:30 at night, my kids are in bed, I can't spend time with them. I can't give them those hugs and cuddles that I do all day working with other people's children. So it's a bit disappointing that I can't find that right balance with just one job,” says Beaver, her voice wavering.

“We understand that an incident took place at Admiral Westphal Elementary School in Dartmouth on May 10, at which time a parent entered the building, disrupted the learning of children, was asked to leave and refused. Police were called and the parent left the premises,” reads an emailed statement from Lindsey Bunin, communications officer of the HRCE, in response to questions about Amanda’s encounter at her daughter’s school.

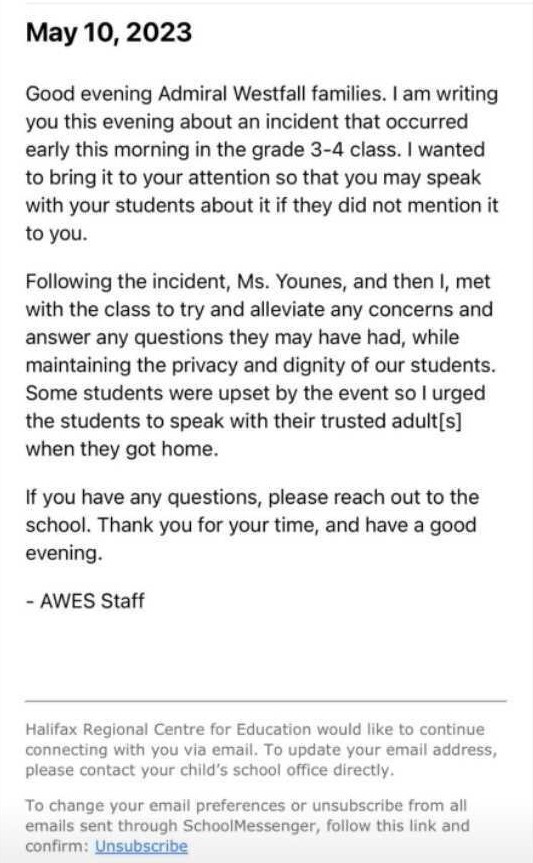

And parents received the following email:

On May 12, Amanda called the school to ask if the Protection of Property Act had been invoked. If Amanda does get charged under the act, she’ll be barred from going on school property for six months. She’ll know for sure what’s going on if or when she gets served the paperwork.

And as it turns out, Amanda was right and the school was wrong. Her daughter was allowed to go back to school on Monday, May 15. It turns out, school is safe enough with a diabetes plan, even though Amanda may not be allowed to go there to help with that plan for the next six months.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the CUPE strike pay would go up to $400 a week on the third week. That was the PSAC strike. CUPE members can expect strike pay to go up to $400 on week eight. Also, since this story was first published, multiple EPAs have reached out to correct their take-home salary ranges. The Coast incorrectly stated most EPAs were taking $500 to $575 a week; for many, it's lower.