Who cares?

You do.

Or you should, anyway, even if you’re not one of the handful of long-time local music scenesters who’ve gone slack-jawed at the thought of two decades passed. Even if you never had a dub of a dub of a dub of the compilation’s Killer Klamz song. Even if you were born in the ’80s. Or the ’90s.

When you’re singing along in the shower to the latest offering from Wintersleep or downloading Joel Plaskett songs from the iTunes Music Store, it’s easy to pass off Out of the Fog (if you’ve even heard of it) as a dusty compilation from a bunch of amateur musicians with a baker’s dozen songs on an over-the-hill format. (Vinyl. Remember what that looks like?)

But the LP is more than an $8 used record-cavern find.

Out of the Fog is the most important album in Halifax alternative music. If you’re a fan of Sloan, if you love Sarah McLachlan, if you miss Halifax’s late-’80s raging hardcore scene, if you ever played video games beside the bar at the Double Deuce or if you go to Stage Nine today, you owe this 1986-released record a sloppy kiss of thanks.

The bands on Out of the Fog—from Violent Femmes-inspired busker Mark Wellner to rockers Basic English to hardcore stalwarts False Security to synth-band I Want—weren’t the first alternative musicians in Halifax. But the album, which blisters with that mix of genres plus new wave, roots-rock, punk and early Goth, was the first compilation of Halifax underground bands ever laid down. It was followed by Cod Can’t Hear, Never Mind the Molluscs, Hear and Now and other Halifax compilations.

“The album,” says Greg Clark, whose name you won’t find anywhere on Out of the Fog’s cover or insert, though his involvement was nothing less than fundamental, “gave a little bit of credibility to the scene. CKDU was just starting; it was a place for the bands to be played.”

If Dalhousie campus radio station CKDU (in 1986, a year old and barely on its feet) was a place for underground bands to be played, the Flamingo was the place for them to actually play.

But the first question in the story of the Flamingo is this: which one?

The legacy started with the all-ages Club Flamingo on Grafton Street (in the former Alfredo, Weinstein and Ho spot). After four months it moved to Gottingen Street in the space of the former Cove Theatre (now decrepit, graffiti-laden and exasperatingly empty). After a year, the club picked up speakers and moved again, becoming the licensed Pub Flamingo on Salter Street (taking up half the space the Pacifico does now).

There have been other Greg Clark-backed venues—Waldo’s on Sackville; Birdland Cabaret on Brunswick; Granville Hall; the legendary Double Deuce Roadhouse on Hollis. These days, Clark, now that he’s through with his five-year stint booking bands at the Marquee, has settled into his most recent roost, Stage Nine, the alt-music Mecca overlooking Pizza Corner at Grafton and Blowers.

But any mention of Out of the Fog or Halifax underground music in the ’80s, or Greg Clark’s influence, would be only half-done without a mention of Backstreet Amusements (1980-89). Backstreet was Clark’s Prince Street video arcade, where local teenagers who didn’t look like cast members from The Breakfast Club (except maybe Ally Sheedy’s reclusive Goth girl character before she was forced by Molly Ringwald to wear lipstick and brush her hair out of her face) went instead of the mall to feel at home.

Backstreet might have been just a cave-like arcade (it’s Rock Candy these days) but as an influence on Halifax alternative culture it has staying power. A thread on the message board of halifaxlocals.com called “backstreet amusements circa 1984-89” that was started in January sits at just under 300 pages. That’s right: pages.

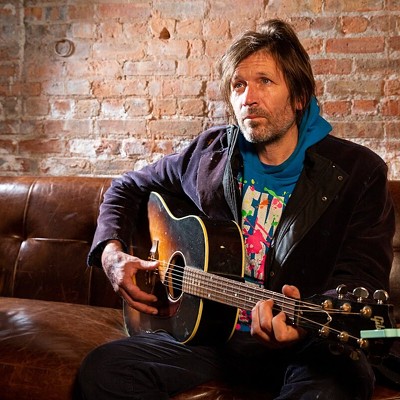

Backstreet Amusements planted the seed for Clark’s lifetime of nurturing the alternative music scene. “I could tell from the arcade,” he says, 51 and still representing indie music in a Grand Theft Bus t-shirt, “they needed a place to hang out and they needed a place for bands to play.”

Club Flamingo launched when Clark got into business with Keith Tufts, then 24, station manager at CKDU, and Derrick Honig, then 18, who worked for Clark at Back-street. “We bought the Cove,” Clark says. “It was cheap. We opened in the fall of ’86.”

The venue had a repertory cinema element and an intended record label too—Flamingo Records—though Out of the Fog was the first and last release. (Clark says, “Getting involved with one band was a bit of a conflict of interest in terms of trying to promote everybody. There was volatility.”) Clark, Tufts and Honig also launched a short-lived entertainment magazine, New Works, that lasted about a year.

The recordings for Out of the Fog were all (but one) done at City Studios in the Brewery Market and engineered by Mark Clifford, who did live sound at the Club Flamingo on Gottingen. Clark doesn’t remember how much the whole thing cost to put together—“I think it was between $3,000 and $5,000. There were only 1,000 pressed. I don’t even have one.” (Taz Records on Gottingen doesn’t either; nor Bedford’s vinyl paradise, Select Sounds; it’s also nowhere to be seen on eBay. Maybe Clark is right when he says “You could probably get 500 bucks for one now.”)

The Flamingo partners paid for the album by putting on shows. “We were calling it the Metro Music Compilation Project,” he laughs. “We did a series of shows which were the Metro Music Showcases. We did them at McInnes Room, one at the Holiday Inn, one at the LBR”—Lord Nelson Beverage Room—“one at the Misty Moon.”

Colleen Britton remembers that time. She was 18 and the drummer for Halifax’s most successful underground band, Jellyfishbabies.

The club opening “was in October. We played that night. Before, we used to have to rent our own space just to have a show.”

Peter Arsenault, Britton’s Jellyfishbabies bandmate and later a member of Montreal skate rock outfit the Doughboys and All Systems Go, remembers too: “Everything happened that year.”

By the opening of the Flamingo, Jellyfishbabies, a two-year-old power rock quartet, had a self-titled full-length but still jammed in Britton’s parents’ basement—“that’s where the drums were.” Out of the blue, Britton, Arsenault and bandmates Dave Schellenberg and Scott Kendall didn’t have to rent space at Veith House, the Y or the Bible Society to play live. “All of a sudden there was a place for bands to play and things were going,” Arsenault says. There was stability on the scene for the first time.

Before that, local alternative recordings practically didn’t exist. Gigs were catch-as-catch-can. “The best a band in Halifax could do was to drive up to Moncton to do a punk gig,” says John Stevenson, who worked at CKDU during its founding. “Or they could go to Wolfville and no one shows up. It wasn’t sustainable.”

Stevenson, 41, was a Truro native doing a theatre degree at Dalhousie when he was asked to produce a radio drama show on then-about-to-launch CKDU. The station hit the air February 1, 1985, but Stevenson never managed to produce a lick of radio drama. He also never left the campus radio fold. He still does policy work from his Ottawa homebase.

Stevenson also helps keep the fire going on the Halifax scene-that-was. He runs tranquileye.com, a blog and archive site where, as a side project, he hosts an extensive sampling on stories on the Halifax music scene from the mid-’80s through 2000.

“I ended up saving a lot of crap from that time,” he jokes. Stevenson is in the enviable position of having dubbed hoards of the demo tapes that came streaming into CKDU in the late ’80s; cassettes whose originals were destroyed when one of the station’s overnight DJs taped over them. “I’ve digitized them,” Stevenson says, “but I don’t know if I’m going to put them up. , it’ll probably be a couple years.”

From the summer of ’85 until the summer of ’86, Stevenson co-edited (with Craig Benjamin) New Works, the Flamingo-driven entertainment magazine. “In the media scene in the city at that point,” Stevenson says, “there were no people of colour on TV. That’s something we did in New Works, we said, hello, there are these other communities here. It was a very dynamic few years.

“There wasn’t anything coming out of Halifax for ages and ages,” Stevenson says of the pre-Out of the Fog era. “Then suddenly there were charts coming out and people were sending in tapes and then Out of the Fog came out and then other people did albums. People were saying, hold on, there’s all this stuff happening here and it’s kind of interesting.”

It all sounds serendipitous—the magical blip in Halifax underground music when CKDU busted out, the Flamingo found its stride and the sound of the scene was available for the first time for take-out order on Out of the Fog.

But that peaking scene was more slow simmer than flash-fry.

There were earlier bands on the Halifax alternative landscape—Urban Attack, Agro, Nobody’s Heroes, Staja-Tanz, Fair Warning and The Euthenics among them—bands that were seminal to the birth and incubation of the scene but who burnt out or broke up or blew away.

The Halifax landscape’s earlier bands “blazed the path for the current underground music scene,” according to Out of the Fog’s back cover blurb (oddly, considering the album’s emphasis on documentation, Clark can’t remember who wrote it).

These pioneer musicians, while they might have strayed from their bands, for the most part didn’t quit making music. Urban Attack spawned Out of the Fog’s side one sludge punks Dogfood; the Vulgarians link to Sarah McLachlan’s band on the compilation, October Game; Media Blitz produced short-lived off-shoot and side one Out of the Fog inhabitant Karma Wolves; Registered Vote’s progeny was Mike Brennan’s Out of the Fog project The Lonestars; Vacant Lot turns to Topsiders, turns to Ridge of Tears (side one), turns to Misery Goats (side two).

That incestuous family tree kept growing, but more rapidly and in bigger leaps after the release of Out of the Fog and the establishment of the Flamingo and CKDU.

That time “was an inspiration for a lot of people,” says Colleen Britton, who was one of only three women (alongside October Game’s McLachlan and Anita Lipohar from Misery Goats) on the album of 53 musicians. “It inspired a lot of the younger generation to go and form their own bands. It made the scene bigger.”

It gave Halifax’s alternative music sound a reputation. Before pret-a-porter grunge. Before Sloan signed to Geffen. Before Melody Maker anointed Halifax “the new Seattle” and Harper’s Bazaar wrote about the early ’90s scene that joined Halifax with “an entire constellation of hip North American cities” on par with Chapel Hill, North Carolina and Austin, Texas.

“By ’89 I had gone to Toronto,” says Peter Arsenault, who left Halifax with the rest of the members of Jellyfishbabies (except drummer Britton) to re-establish the band in a bigger centre. “We would play there and people would say, ‘Wow, you’re a Halifax band.’ And it meant something.”

After that, he says, “I think people were actually starting to come here to be a part of it.”

They were. Bands emigrated to the city. Promoters came too. Colin MacKenzie, who would later move to Halifax from Ottawa to work at CKDU, was a DJ at the University of Ottawa’s CHUO. He recalls receiving Out of the Fog at the campus radio station. He remembers thinking “Halifax has its shit together.”

In 1988, CKDU hosted the National Campus and Community Radio Conference. MacKenzie says, “People came back (from Halifax) and they were totally psyched. Halifax was like…like it had it goin’ on.”

“In a sense was deliberate,” says Roland Blinn, who performs the tongue-in-cheek ditty “Flamingos My Love” on Out of the Fog with his band, the Fishermen. “And it snowballed.”

“Bands come and go and people break up and people join other bands,” says Greg Clark. “But that’s the main thing with any scene, the sheer quantity of musicians.”

The reverberations are still felt today, 20 years after Out of the Fog.

“There’s a lot of stuff percolating. Today you could do several compilations for each of the genres that are on that album,” Clark says. “There are just so many bands around.”

There’s even a Halifax band called October Game, which takes its name from the old October Game on Out of the Fog.

“I was introduced through my mom,” says October Game lead guitar player and vocalist, 16-year-old Matthew Beasant-McKeown. “Sarah McLachlan has a great style.”

The band contacted McLachlan through her record company to see if it was OK to take the name.

Today’s October Game, which Beasant-McKeown characterizes as “between Dave Matthews and John Mayer” and not all that similar in sound to the McLachlan-led post-punk band, got started in autumn 2004. A year-and-a-half old, the band has already recorded, released and sold-out its debut full-length and is recording its second effort.

In 1986, being that prolific would have been absurd for practically every band on Out of the Fog (save the exception to the rule, Jellyfishbabies).

“If you were going to put that compilation together today,” says Greg Clark, “all the bands would already have recorded their own albums.”

But two decades ago, compilation albums were the first step for most musicians to stretch their sounds beyond venue and jam space walls.

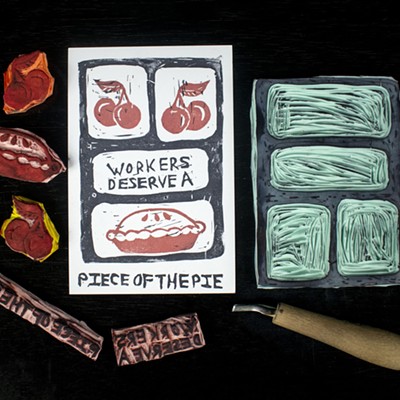

At the time of Out of the Fog’s release, Roland Blinn, who still lives in Halifax and records mostly at home, had been performing original music on the scene since the late ’70s. Still, he says, “It appealed to me, because, it was like, I got to be on a piece of vinyl.”

Compilation albums were also the first step for many music fans—especially alternative music enthusiasts in venue-scarce Halifax—to find new music. And new genres. Peeling back the wrap on a compilation album used to be like opening a Moirs Pot of Gold on a Christmas afternoon. You never quite knew what you were going to get, but you knew it was worth trying and you might find something you loved.

Jellyfishbabies drummer Colleen Britton was, and is, a dyed-in-the-wool punk. Nevertheless, “I still listen to the album all the way through,” she says. “I ran into Sarah last time she was here and she asked me if I was coming to her show. And I was like: you know I’m not that into your style of music. If you do some Dead Kennedy covers, maybe.

“But, see, I appreciate all the different styles of music, even if I don’t necessarily like them.”

At its launch, CKDU’s signal was 50 watts. If you had an FM antenna on a stereo receiver and you were in the city, it was OK. Car reception, not so hot. For music-hungry Haligonians, the options were limited: read magazines and scrabble at record shop shelves. If you were lucky, you had out-of-town friends who could send you mixed tapes. When a compilation came out, you scooped it up.

“Other cities were doing it too, putting together compilations,” says Peter Arsenault. “Of course I bought them. There were like 25 bands on it. It was like, oh man, you should check out this new band I heard!”

Britton says, “That’s why I love the Internet. Because I used to have to go scour stores to find music when I was travelling or playing. Now I just download MP3s.”

“The way people find music is not the way people found music 20 years ago,” explains John Stevenson. “It wouldn’t make sense to do again. I kind of mourn that, because I liked the community aspect of it, but it’s just the media-technology reality.”

“Now,” Britton says, “people make their own compilations.”

By the time Out of the Fog came out in October 1986 and the Club Flamingo was rooted for the up-till-then largely nomadic underground scene, most of the 13 bands on the album had already broken up or moved on.

In many ways, it was just more of the same on the Halifax alternative scene. And the hopeful endnote of the album’s back-cover blurb (“If this record can help, in any way, to get where they want to go, then it will have been well worth the effort.”) was nauseatingly—if predictably—moot.

“It was very frustrating to be a musician in the city at that time,” says John Stevenson. “It was always a crap shoot who got famous and who didn’t get famous. Particularly what happened with Sarah. I could have picked three or four people that could have happened to…It’s a roll of the dice. Somebody became a big star and everyone else just went on with their lives.”

Out of the Fog might not have made a tangible difference in the lives of many, or any, musicians who were on the album. I wanted to ask Sarah McLachlan about this, but the Lilith Fair founder and multiple Grammy winner is taking time off to travel with her family and isn’t taking interview requests.

But where this first compilation of Halifax alternative music failed to be a star-maker for everyone, it had a bigger impact than anyone involved could know at the time. At least (or perhaps at best), Out of the Fog got Halifax music fans where we wanted to go.

“With Out of the Fog, institutions got established,” says John Stevenson. “The album wasn’t the only part of that, but it showed that you could make an LP and it could come out of Halifax. In that sense it was pivotal.”