Whatever you think you know about the Irvings, you’re going to learn more in Irving vs Irving. The new book by veteran reporter Jacques Poitras looks into the history of Canada’s third wealthiest family, examining untold stories as the New Brunswick tycoons monopolize print media, fleece the government and battle against their own kin. It’s an engrossing read, filled with the kind of magnificent machinations and bizarre anecdotes you’d want from one of the Maritimes’ most private empires. Jacques will be all over local media this week, as Irving vs Irving officially launches, but he took some time to chat with me over the phone from Saint John.

One of my first job offers was actually for Here magazine. A week before I was supposed to move out to Saint John, the editor called to say there was a hiring freeze and they had to take the offer back.

Yeah, well, you dodged a bullet there, my friend.

I saw the memo from Jamie Irving you put up on Twitter [The Brunswick News vice-president informed all current and past employees not to speak with media after Poitras contacted him for an interview], was that the typical response from the Irvings while you were researching the book?

No, not at all. Jamie's father and grandfather both gave me interviews. I guess it was interesting that there was obviously a decision at some level to cooperate to the extant that they would talk to me about the newspapers, but the person actually running them day-to-day was not going to be in the interview. That was kind of curious. I don't know that was a coordinated thing or that Jamie just made his own decision, but certainly he would have been a revealing interview.

The Irvings, they're very private people. So I went in sort of prepared for no cooperation at all, went back and forth a bit on getting the older Mr. Irving and Jim Irving. I was happy when I got the interview, and there were some revealing things they said.

On the other side of the family, on the Arthur side of the family, there was no cooperation at all. Literally Irving Oil did not answer my emails requesting an interview, and did not answer my emails asking them to please tell me if they were definitively turning down an interview. What I finally did in that case was I bought a $150 ticket to a Red Cross charity dinner in Saint John where Mr. Arthur Irving was being honoured so I could actually walk up to him and ask him for an interview. He said "no," but I wanted to satisfy myself that he was aware of the request personally and was not interested.

I imagine it wasn't as difficult to speak with former and current reporters.

Former employees were much easier. Really, the longer the time elapsed since their time at the paper, the easier it was in general.

It struck me how for many decades the Irving family almost seemed afraid to be directly influencing their papers. They very much wanted to not be involved in that way, and yet it would happen anyway; mostly on the stories that weren't covered.

This surprised me a bit too. Not only did they not take a hands-on role in the '70s and '80s, but they were actually afraid of taking on a hands-on role because they really did fear that the government would then regulate if there were any evidence of them interfering.

Now, as I said, they had, as a general rule, editors and publishers that were not going to do a lot of digging on the Irvings. I think these editors for the most part were cut from the same cloth, in that they were not investigative, digging types who did not create that kind of culture in the newsroom.

I thought it was really telling when they hired Valerie Millen to be the general manager of the Telegraph-Journal in '91, '92 and J. K. Irving told her, you are not to let any member of my family, including me, tell you what to put in the newspaper because we don't want you giving government any grounds to hold an inquiry or investigate us. That was really interesting that that happened. But I think that doesn't necessarily mean it's going to be independent journalism. I think a lot of the editors were very cautious about the Irving story. And then we see these periods where someone come in who does take that sort of investigative approach, and they are allowed to run with it for a time.

Then we get to the '90s, where they decide to be more hands on from a business point of view, and that reopens the question.

There's also a lot of weird ideas that come up now and then, like the one manager who wanted uniforms for the newsroom.

Yeah, that was actually John Irving. Well, if it works in a gas station, why not?

One of the interesting evolutions is, they were keeping them at arm's length, but when they did get involved from time to time they had really bizarre ideas about the newspapers. I don't think they understood how unique a product a newspaper is. They don't seem to understand that it's something very different than any sort of mass manufacturing or processing industry they would have.

There's a moment in the book, during the interview with J. K. and Jim where J. K. says in most of our operations if something happened to a manager we could walk into that mill the next day and run it ourselves until they found a new manager. But he said newspapers are different, we wouldn't know what to do with them. That I think is a recognition that this kind of enterprise is unique. But then Jim responds to him immediately and says, well yeah, there's a creative side but it's a business. It has to generate revenue. So the idea that it's just another unit spitting out product and revenue is part of the issue, I think.

With all the shake-ups, both professionally and personally for the Irvings over the last couple decades, do you think they'll ever just divest themselves of this print media empire and sell off the newspapers?

I don't think so. I think with K.C. Irving himself, he didn't want someone else coming into the market and buying a newspaper or starting a newspaper that would scrutinize his operations. I think that was his reason, that seemed to be the reason. The later generations it was different. Then when we get to the '90s, and this is just before the Internet really took off, the papers were making good money so at that point I think they saw it as a money generator.

Now, it'll be interesting to see what'll happen. I don't think they'll ever sell them, but it's now transforming so much into an online product, and there's so many other options available, journalistically, in the province. There's little things popping up here and there, blogs, people posting videos, analyzing the forrest industry, things like that. The idea of holding onto them so no one else comes into the market and scrutinizes them is kind of old fashioned. That's an outdated idea, with all the new media possibilities.

I guess I don't really know what the answer is, but culturally, in their bones they are not the kind of people to sell properties. They get bigger, they don't get smaller. So I don't see it happening.

Do you feel the Irving empire is in decline?

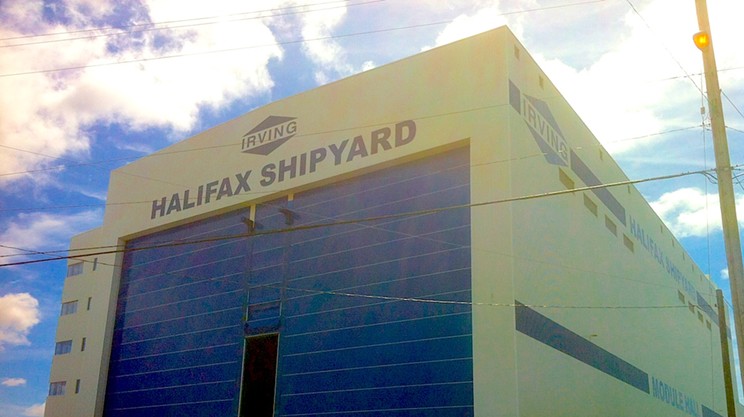

I don't think it's in decline. I think it has transformed itself. It's really two empires now. Irving Oil is one entity, and J.D.I., which owns the shipyard in Halifax and the forestry industry, is another entity. So, we're really not talking about an empire anymore.

At the end, I say it's kind of interesting because the forest business got what it wanted from the provincial government in terms of allocation and it keeps going. The oil company, Kenneth [Irving] looked at turning it into a more of a green energy, natural gas based enterprise before he left. Really, now with the energy east pipeline that's planned to come from Alberta with crude, Irving Oil has really refocused back on its original business; which is processing crude and selling it.

What's interesting is that it's the newspaper business that is really the most changed. It's gone all-in online with a hard paywall subscription model. I got all the internal newsletters from when they were building the new website, and they talked about a day when newspapers won't exist as print products. If anyone is really forward looking, it's the newspaper business itself.

As a corporate culture in the province, as a presence a dominating force, I just don't see it. I don't see them going away, selling off. They're not diversified geographically. I don't see them dropping their assets here in favour of somewhere else. It's in their DNA to keep this machine, these two machines, running.

How close is the story of New Brunswick to the story of the Irvings? New Brunswick history is printed literally on Irving paper, in Irving ink.

Well actually they don't make newspaper newsprint anymore. That's one thing that's kind of interesting. They themselves a few years ago recognized it was better for business to produce something other than newsprint. The newspapers even exist outside the vertical integration model of the forestry company. For years, one of the theories is they owned the newspapers because they liked to own the supplier and the buyer of their products. The newspapers were a reliable buyer for newsprint, but they're out of that now. For New Brunswickers, it's hard to imagine the Irvings buying their newsprint from someone else.

The business, economic story of the province, and to some extant the governance story of the province, really are, it's one in the same. I don't think you can talk in New Brunswick about the economy, and business and the relationship between business and government without talking about the Irvings.

Irving vs Irving: Canada's Feuding Billionaires and the Stories they won't Tell is in bookstores now.