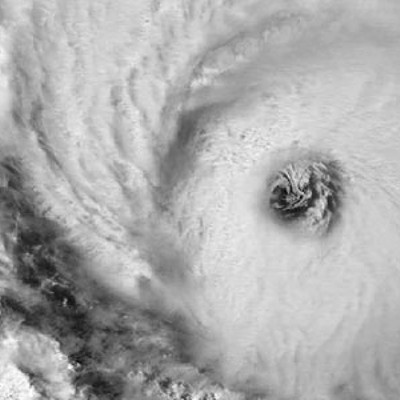

Considering the size and weight, the oak tree that fell on my neighbour’s house at the height of Hurricane Juan landed softly, settling on the roof and bending gutters, but causing little other destruction. My neighbour is a handy-man type of guy, and the gutters will be repaired and replaced in a short Saturday afternoon. The house will survive, but of course the real, irreparable damage has been done with the loss of the hundred-year-plus tree, and my neighbour’s perspective when he looks out the back window is forever changed.

Thousands of other people across HRM are like my neighbour, coming to grips with a change of perspective due to the loss of trees across the region. In the wake of the storm, everyone seems to have a tree story—or two or three tree stories—to tell. A tree on a house, a tree that just missed a house, a tree that toppled and pulled up a massive root ball, brought down power lines and blocked off a street. The morning after, people surveyed the damage in shock, not quite believing a favourite tree that had stood throughout their lifetime was gone.

We literally grow up with our neighbourhood trees. We climb them, swing on them and build forts in them. Year after year we take shelter under them, waiting for the school bus. We apply a sharp knife to their bark to make a public declaration—KD LUVS TF—and then, long after KD has forgotten what TF looked like, the tree maintains a permanent record that once they LUVED. Many of us who grow up and leave our parent’s homes return years later and are struck first and foremost by the changes to the trees. Their physical growth over the years seems to dwarf whatever emotional growth we’ve gone through. Standing under them we’re right back to being kids again, and the thought in the back of our minds that wherever we go and whatever we do our favourite tree will always be there when we return is humbling and comforting all at once.

“Trees are bigger and stronger and older than we are and when they break it exposes a frailty we don’t expect and changes our horizons,” says Murray Russell, a horticulturist with Atlantic Gardens who has more than 20 years experience working with trees. Russell himself lost almost a hundred trees on his two acres of property, and guesstimates the numbers across HRM to be upward of 10,000. He was out first thing Monday morning to survey the damage and compare notes with neighbours.

“I was struck by the random nature of the trees that fell,” he says. “One giant tree would be down, and right next to it some scrawny weakling would still be standing. I couldn’t see the logic.”

Russell says that the loss of so many trees in HRM is an indication that trees grow to sizes in Nova Scotia in conditions that simply aren’t conducive to growing large trees.

“I’m surprised that even deep-rooted trees like oak and ash behaved like shallow-rooted trees in coming up by their roots,” he says. “What it revealed to me is the dreadful lack of topsoil we have here. Many trees pulled up two inches of sod revealing pure rock and gravel beneath.”

The first instinct many of us have is to try and save our trees, to straighten the ones that have toppled and exposed their roots, hoping that by replacing the tree in its original hole all will be well. Sadly, Russell says, in most cases it’s unlikely such a strategy will work.

“As a horticulturist, many people have been asking me if they can just pull their trees back up, but doing that kind of repair is an area that very few people have experience in, putting the giants back up again,” he says. “I assume that the general rules of transplanting apply, in that if you’ve lost 50 percent of the roots, you have to cut 50 percent of the tree, and then you can cable and brace and feed it, and theoretically it has potential. But it’s a question of what kind of machinery you have at your disposal. I wouldn’t recommend that people invest a lot in the effort, with only marginal chances of success with large trees.”

What we can do, Russell says, is to start a new cycle of growth by using what the loss of so many trees has taught us about the conditions in which we expect them to grow.

“To start again, people need to do a little planning, and can save themselves generations of headaches by putting the right tree in the right place,” he says. “Many of the trees that came down were simply too close to a house, where there could only be root growth to one side, so of course they were unstable. And it’s a shame that people don’t make the investment in the soil, to improve the dreadful soil conditions we have in Halifax to the greatest depth that they can. The old adage is that you don’t put a $20 tree into a $10 hole.”

Besides climbing and swinging and measuring our own growth by the trees, we also use trees as a signpost: “Ours is the house next to the giant maple, you can’t miss it,” we say. Somehow, “next to the giant maple stump,” lacks the same certainty. About a year ago I sent a website address that proclaimed this to be “The City of Trees” to a friend in England who was looking for information on the history of Halifax. It’s a motto not many of us have ever considered, mainly because we’ve come to take the trees for granted. Now, people are saying, with the loss of so many trees the landscape of the city has changed forever. Perhaps the lesson of the past week is to think of that motto a little more often, and perhaps appreciate a little more the trees in our lives.