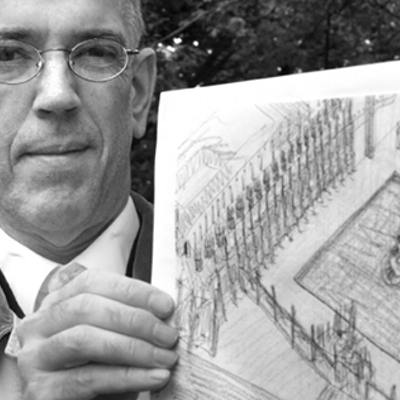

David Clark is on top of the world, or nearer to it. "I'm on top of Whistler Mountain," the Halifax-based new media artist says. He's accompanied by David Ogborn, an electronics artist and composer from Hamilton.

"Basically I've gotten 20 yards down the hill," says Clark, asking for a 20-minute reprieve before continuing the conversation.

And Clark and Ogborn are off to finish their run down the slopes.

The two artists have hopped on the hills after spending more than 12 hours the day before at the Whistler Public Library, where they reassembled and installed Waterfall, a video sculpture about water consumption and conservation.

For the duration of the Olympic and Para-Olympic winter games, the library will house Whistler's Canada Olympic House. Mainly a hangout for athletes, media, sponsors and officials, the facility will have open houses and public tours, too.

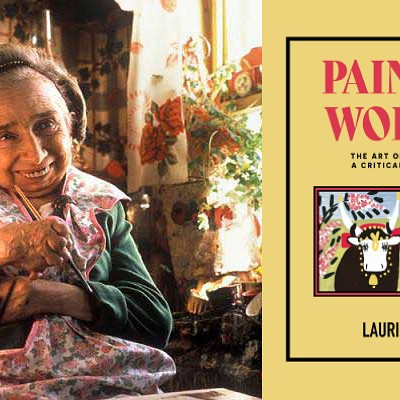

Reached at her NSCAD office in a separate call, Kim Morgan, a sculptor, installation artist and teacher, confirms Waterfall uses "an actual vending machine---a Snack Shack 400 or something like that---that I was able to purchase through this guy who distributes the machines at NSCAD."

Morgan, who moved to Halifax from Regina about a year-and-a-half ago, heads west to Whistler next week.

Last year, she was commissioned by the Canadian Wildlife Federation, a national non-profit environmental education and advocacy organization, and accredited Olympic exhibitor, to create a work for the games.

She assembled a group (Clark, Ogborn and Regina new media artist Rachel Viader Knowles) to collaborate on the project, mainly via Skype.

Drawing on everyone's input and interests, they conceived of the metaphorical vending machine. Instead of snacks and drinks, a series of images, such as a drinking glass, gardening can, washing machines, car washes, dishwashers and showers, sit in the metal coils. When a person makes a selection, a sequence plays out.

"Each video is a 15-minute loop of how we use water every day," says Morgan. "Let's say you press A1 and you see water pouring into this glass. Then you see someone picking it up."

When the selection finishes, the image drops to reveal the source behind our mechanisms and consumption: a roaring waterfall. Visitors retrieve only a thought, a valuable one, according to these artists.

"We think of water as being free and there's no consequence to using it," says Clark.

"I hope it makes people stop and think about the connection between how we use water and where it comes from," says Morgan, adding, "the idea of water as a consumer product---buying bottled water."

Asked if he's spotted any branded bottles of water in Whistler, Clark reports that he hasn't yet. "There's definitely wine, but I haven't seen bottled water. I'm sure there is," he says.

Of course, a major part of the Olympics brand and industry, as far as the winter games go, is snow---water in a cold, solid state.

"The idea was to draw attention to the environmental infrastructure the winter games depend on," says Rick Bates, CWF executive director, on the phone from a hotel in Ottawa. The CWF head office is in Kanata, in the nation capital's west end, but Bates is based in Regina.

He knew of Morgan's work, particularly how she combined artistic practice, scientific research and environmental awareness. That's why, he says, he approached her about the CWF commission, which was initially budgeted at $20,000. Bates hasn't seen the piece yet, but believes it'll work for CWF. "We wanted something a little more intrusive than other means of communication---and a little more challenging as well," he says.

As a well-established non-profit entity, CWF has its own identity, goals, its own brand. But none of that was brought to bear on the artists, Bates says. "We were very sensitive to the need to keep it art."

Morgan is clear on this. "We're not just doing a commercial. It's a poetic, artistic vision around water usage," she says. Occasionally, she continues, the two sides struggled to simply understand each other, to find a "common vocabulary."

Morgan likens the situation to a class she's teaching at NSCAD. "I have students out in the city now doing site-specific installations and most people think that means a mural on the wall. So, it's just stepping back from that and finding the language where you can say, 'Well, actually it's not a mural. It's maybe something you've never seen before. Here's how it works.'"

Back in Whistler, which Clark describes as an "outdoor mall," the library was "being gussied up, so it's full of sponsorship things, multimedia videos and stuff like that."

Amid all this activity, Waterfall already stood out to at least one viewer: "We got a dirty look from the guy delivering the Coke machine."