Scale works both ways on peoples’ awareness and experience of their surroundings: the small fascinates, the large looms.

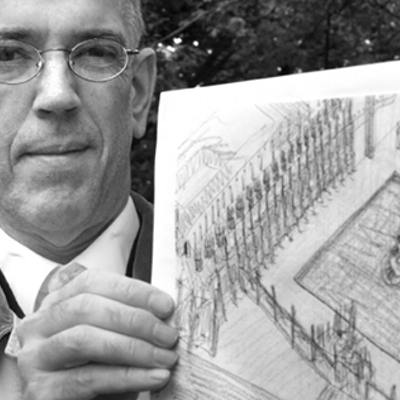

Cape Breton artist Carl Zimmerman uses both directions in scale in Landmarks of Industrial Britain, running until January 7 at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. His photographs of seemingly massive abandoned buildings from 19th century northern England are, in fact, images of architectural models he builds in his studio.

Once photographed, Zimmerman digitally sets the buildings in bare, brushy landscapes and against cloudy, dull skies. Tiny human figures wander in these interior spaces or approach the exterior facades, amplifying the illusion of the buildings’ architectural heft.

“For me scale is directly related to the idea of the sublime, particularly the historical idea of the sublime as an awe-inspiring, overwhelming force of nature,” writes Zimmerman by email. “Since the 18th century it has been a not-uncommon practice for artists to see the sublime in terms of nature but also in cultural terms as it applies to architecture.”

Only with the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the period of Zimmerman’s buildings, he says, “truly gigantic buildings could realistically be attempted, a trend that possibly reached its apex with Speer. Gigantic architecture of late has suffered a loss of credibility due to the likes of Saddam or Nicolae Ceausescu but the impulse to participate in the something beyond words, that is larger than ourselves, remains.”

Gigantic, monolithic or monumental architecture troubles, even offends, as many people as it enchants. By achieving a sense of grand scale, and grandeur, using scaled-down constructions, Zimmerman offers a pause in the big versus small debate. Though he’s not, he says, directly addressing any current architectural debates, such as Hariri’s so-called “Twisted Towers” proposed for downtown Halifax, Zimmerman’s work suggests big is beautiful and thoughtful, an expression that goes beyond the desire to erect something to tower over the masses.

According to Zimmerman’s vision, this series of nine interior and exterior spaces represent the core of a fictional “utopian city” built by a socialist workers’ state.

He offers an example. “For me the overriding consideration was the creation of almost unlimited interior space. In the Unitarian Church piece for instance, I wanted something that might reflect the general upheaval in religion that was transforming Britain in the 19th century,” he explains, when the Unitarians invited dissenting Protestants to join them against the Church of England. He sees the image “representing an erosion of traditional religious values and institutions but an uncertainty about what might replace it.”

The uncertainty and the striving echo in these empty spaces, triggering a sense of sadness and pathos in viewers. The artist creates the emotional tone through details—broken glass, peeling paint, the way the light filters in.

Ray Cronin, curator of contemporary art at the AGNS, points to Zimmerman’s comment on modernism, the zenith of architecture that expressed humanity’s desire for progress. “Modernism, in its largest sense, felt that the world—that the lot of humanity—could be bettered if it was controlled and focused, systematized,” Cronin offers. “Carl’s work makes manifest ruins of that belief system, ruins that are all around us actually, just not in such a clarified, distilled, manner.”

Cronin invited Robin Metcalfe, before he joined Saint Mary’s Art Gallery as director and curator, to curate this show. Metcalfe writes that Zimmerman underscores how “gigantism…characterizes regimes condemned by their own inflated sense of historic mission.”

Still, neither Zimmerman, Cronin nor Metcalfe suggest we should raze every monumentally sized building in our midst.

“I think it’s important to maintain the major architecture of any significant period,” states Zimmerman, to resist the impulse to build bigger things—elbowing out the previous period’s big things—on a belief that “the past does not exist.”

Landmarks of Industrial Britain runs until January 7, 2007 at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 1723 Hollis.