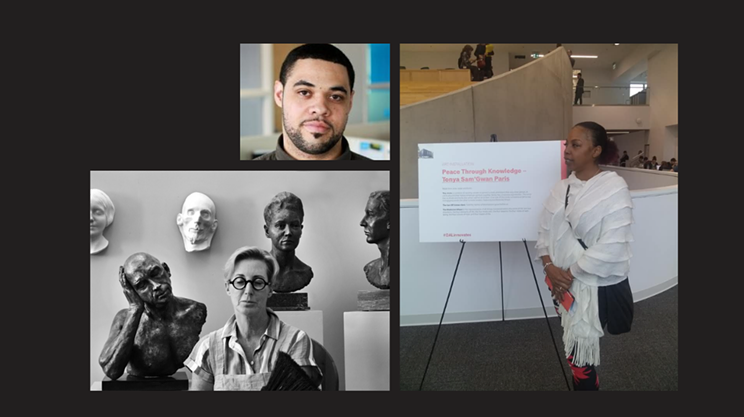

Forty-five-year-old Tonya Lynn Paris is a petite five-foot-two with a large voice and strong personality. Her nature embodies that of a courageous woman, always prepared to prove her critics wrong.

The single mother of three boys' life journey showed a willingness to go against the odds. In 2015, she picked up a paintbrush. Today, under the name Sam'gwan the Artist, she is receiving more and more recognition for her evocative art.

One of the themes she regularly explores in her work is her proud identity as a Black and Indigenous woman. Her mother Debra Paris Perry, now her momager, exposed her siblings and her to positive aspects of both cultures. "Growing up myself being bicultural was very difficult, finding where you fit." says Paris Perry. "So, I didn't want my kids to experience the same difficulty if I could help it as a conscious parent."

Paris goes by the name Sam'gwan the Artist. Sam'gwan—meaning water in Mi'kmaq—was given to her by an elder, describing her as a fluid individual able to adapt to any surroundings, and giver of life.

Finding her voice through art is far from the vision she had growing up. Instead, she envisioned becoming a police officer. "I wanted to be that bridge between my community and the police department," she says.

Living in Mulgrave Park, she observed strained communications and police brutality towards the Black community and was determined to make a difference.

Too young to join the police force at 17, she joined the Canadian armed forces and became a military police officer. She trained with the Halifax Regional Police Department, where she experienced racism and sexism. "It was a good ol' boys' club, they didn't want women there," she says. "When myself and Robyn Atwell came, it was like stirring up the pot. You would hear little under-the-breath remarks."

Some officers mimicked slapping her on the ass, but never followed through due to repercussions from her instructor. "A slap on the ass would have been a broken wrist," she says. Similarly, former Halifax Regional Police chief Frank Beazley was supportive when she brought forth her issues. Nonetheless, she adds, "Everything Robyn Atwell does speak on is absolutely true."

Atwell, the first Black female sergeant in Halifax, filed a human rights complaint against the Regional Police in 2008, accusing the department of discrimination.

In 1992, she and Atwell attended the same cadet class, but took different paths. Paris left the force in 1993 after marrying and relocating to the United States. She returned to Halifax eight years later, opening a hair salon on Oxford Street. Later she drove buses, the Big Lift shuttle and multiple other vehicles in the city. Paris Perry says, "I can say one thing about my daughter—when she puts her mind to something, she gets it done."

Paris says her mother is the one person who always encouraged her to be an artist. She doodled occasionally and drew cartoons, but never painted until about two years ago. She didn't believe she was good enough, much less expected she could do it professionally.

Over time, she has built confidence with the help of her mentor, Artie Barksdale III, who is formally trained and teaches her artistic techniques. Thus far, some of her clients have been Dalhousie University, Halifax Cycling Coalition and the United Church of Canada. Paris' future goal is to open a gallery where the "focal point is raw Indigenous art."

Paris describes her paintings as having hidden messages. Most powerful to her is the fact that she has a larger voice."You can censor my words," she says, "but you can't censor my art or how people feel."