In the 18 months since the pandemic began, vaccines were developed and approved for global use, drastic public health measures were implemented and largely followed, and new models for stay-at-home working and learning were developed overnight. Given the global cooperation and concentrated effort that's been used to combat COVID-19, some doctors and scientists are looking at how fighting the pandemic can inform tackling the most significant crisis of our time: climate change.

“When I think about what’s on the horizon, for me it’s climate change. As a whole it’s a million times more serious ultimately than this COVID-19 has been,” says Dr. John Ross, former head of the QEII emergency department and current medical director of the telemedicine firm PRAXES, which operates testing for Nova Scotia’s pop-up sites.

“It’s a global problem, and it’s huge. And we do need to feel an urgency around that. With COVID-19, how people have rallied together, and communicated, and created teams like never before: I look at that as almost the minor dress rehearsal for what the climate change crisis is going to start bringing.”

Scientists who study infectious diseases and the environment have warned that climate change will continue to make outbreaks of infectious diseases like COVID more common and more deadly.

According to a 2020 World Meteorological Organization report on signs of climate change, 6.7 million people were displaced from their homes due to natural disasters in 2019 alone. These floods, hurricanes and cyclones are becoming more frequent and powerful. Globally, natural disasters displaced massive numbers of people from their homes in Bangladesh, Philippines, Mozambique, Ethiopia and Bahamas that year. Tropical cyclone activity was up to 72 storms around the world in 2019, an increase from the 27 storms in 2018—which was also above average at the time.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in a statement on Aug 9 that many changes observed in the climate this year are “unprecedented in thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years, and some of the changes already set in motion—such as continued sea level rise—are irreversible over hundreds to thousands of years.”

The statement goes on to encourage governments to act: “However, strong and sustained reductions in emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases would limit climate change. While benefits for air quality would come quickly, it could take 20-30 years to see global temperatures stabilize.”

But Canada’s current actions to cut emissions and finance clean energy have been deemed “highly insufficient” alongside Australia and China, according to a Climate Action Tracker report published this week. The vast majority of nations are failing to meet the environmental goals set up in the Paris agreement, which aims to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Ross says it’s clear people have learned lessons throughout COVID in terms of responding to public health orders during a time of emergency, “but for as bad as this has been and as annoying as this has been, it’s nothing compared to what’s on the horizon with climate change and we need to take that seriously.”

There are parallels between the pandemic and the climate crisis in terms of universal impact, says Dalhousie University professor and scientist Rajesh Rajaselvam in an interview. “COVID shows us this level of disruption, the pandemic happened very fast. It was immediate, it killed so many and made an impact very quickly.

“Climate change is something different. It’s very slowly, steadily having a significantly adverse impact on ecosystems, health, humans, economy and everything.”

Rajaselvam teaches economic botany, environmental ecology, nature conservation, and tropical ecology and biodiversity at Dal, with a research focus on conservation and forestry. He is currently working on a review article on connections between COVID and potential action to address the climate emergency. He says it seems as though climate issues are often forgotten by politicians and decision makers.

“If we can control the pandemic because of tremendous coordination for scientists, tremendous funding and extraordinary collaboration,” Rajaselvam says, “why can’t we do this for climate change?”

When the pandemic hit, scientists globally acted fast to develop vaccines to address the massive number of COVID fatalities, more than 4.5 million people killed worldwide. The same level of costly and focused collaboration hasn’t been directed towards addressing climate change.

“We need huge funding, we need collaboration among scientists, government, media and politicians all should work to control climate change. Otherwise we’ll be seeing a huge destruction soon,” says Rajaselvam.

“We’ve learned a great lesson from [COVID], and we need to use it.”

Rajaselvam says governments need to be focusing on carbon emissions and phasing out the use of coal, natural gas and other greenhouse-gas-emitting fuel. “Otherwise the planet won’t survive,” he says. To do this, there needs to be a turn to widespread use of renewable resources.

“Like 100 percent renewable resources. Wind energy, solar energy, hydro, tidal should all be used,” he says.

Fellow Dalhousie professor and scientist Daniel Rainham wants politicians to put a greater focus on confronting the climate crisis. “I’d like to see somebody at the political level acknowledge these pressures that exist and say they will try to develop a strategy to deal with them,” he says in an interview.

Rainham teaches sustainable health systems and is a senior research scientist with the Healthy Populations Institute, where he researches population health science, environmental epidemiology and health geography. He says the best interventions for addressing climate changes will be the ones that prevent further damage—which goes against how people tend to respond to crises.

“This is a problem we have as humans in general, an inability to react proactively. We don’t act in a preventive way, we tend to act in a reactive way.”

Rainham isn’t surprised that climate-change prevention isn’t top of mind, “because it’s not sexy,” he says, and will require a dramatic social change to move away from relying on fossil fuels.

“If I can avoid using coal in my boiler in the basement that’s great. But can everyone do that? I’m not sure,” he says. “And that change doesn’t deal with all the other challenges with fossil fuel consumption, and those challenges require social and cultural solutions.”

Rajaselvam says it’s important to remember nature is capable of regeneration, and that if human-made harm is reduced there is potential for recovery. An example of this is the phasing out of ozone-depleting chemicals over the past 35 years, which has allowed the ozone layer to recover from damage. In 2019 the United Nations announced the ozone layer is expected to fully heal within our lifetime.

“We are part of nature, and destroying nature means destroying us. When we think we are part of nature, then we know that nature can look after itself. And nature has an exceptional ability to rebound and to repair itself,” he says.

“Tremendous man-made impact has slowed down the process of ecosystem recovery, so we need to work on that.”

Politics and the environment

Nova Scotia’s newly formed Progressive Conservative majority government promised in its election campaign to “walk the walk” on the environment front, by ensuring 80 percent of electricity will be supplied by renewable energy by 2030, and by that same year 30 percent of vehicles sold will be zero-emission. The party also promises to protect 20 percent of land and water mass by that year, and fully implement the Lahey Report recommendations for forestry practices. Premier Tim Houston appointed Tim Halman as minister of environment and climate change.

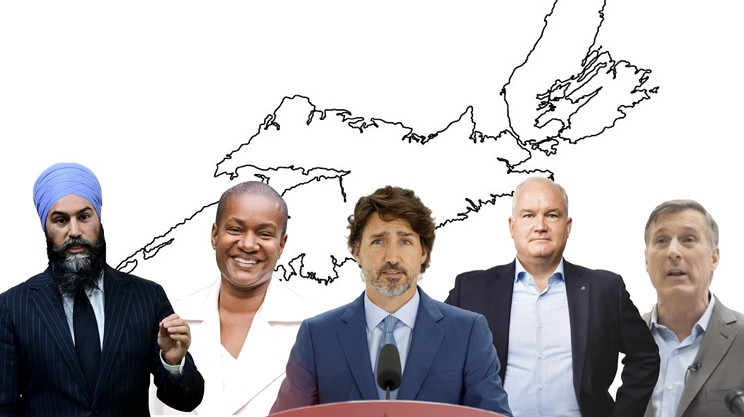

At the federal level, with election day looming September 20, five parties have varying promises on how they’d support the environment. Those promises are excerpted below from The Coast’s pre-election comparison of the party platforms:

The Liberal Party platform says a re-elected government would establish 10 new national parks and 10 new national marine conservation areas in the next five years, doubling the amount of protected Crown land across Canada. The Liberals also promise to invest $50 million in community shoreline and plastic cleanup from the ocean, and to expand the Ghost Gear Program—collecting lost fishing gear, which harms right whales in Atlantic Canadian waters.

The Conservative Party would lower emissions to meet 2030 Paris targets, and promises to eliminate the “unfairness” of prime minister Justin Trudeau’s Bill C-69 environmental protection bill, and “implement a Critical Minerals Strategy to take advantage of Canada’s abundant resources.”

The New Democratic Party says it would aim for a more ambitious greenhouse gas reduction target of 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, and it would create an environmental bill of rights and to protect 30 percent of land, freshwater and oceans by 2030.

The Green Party says it would increase carbon taxes by $25 per tonne every year from 2022 to 2030, and expand the list of non-essential, single-use plastics that will be banned before the end of the year. The party says it would also establish a new office of environmental justice at Environment and Climate Change Canada. Only the Green Party has explicitly said it would put a stop to the offshore oil and gas industry.

The People’s Party of Canada platform falsely claims that “climate change alarmism is based on flawed models that have consistently failed at correctly predicting the future.” The party says there has been “no steady warming in direct relation with increases in CO2 levels,” which is untrue, and says it would withdraw Canada from the United Nations Paris Accords on climate change. The party would also support growing the oil and gas industry.