On Thursday, May 16, Halifax’s Active Transportation Advisory Committee met to hear city staff give a presentation about the HRM’s new Strategic Road “Safety” 😉 Framework. The new framework was sent back to the advisory committee by the transportation standing committee so that staff could change the plan because it’s the kind of road safety plan you’d devise if your job were to increase car traffic efficiency. But, since the people in charge of this plan are traffic engineers, they are blind to the lies they are telling themselves and councillors. So let’s break down the flaws in HRM’s traffic services manager, Roddy MacIntryre’s presentation to the transportation advisory committee.

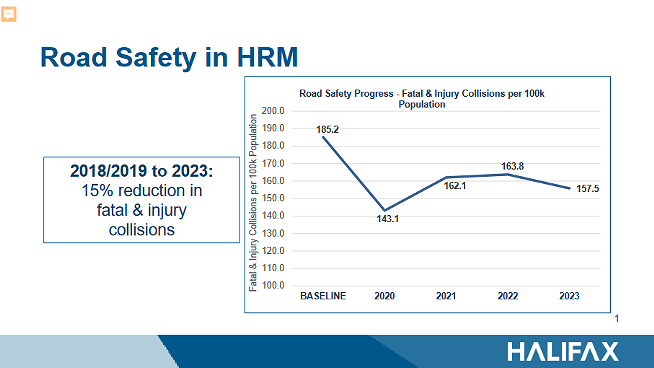

The first slide is a year-over-year road violence trend chart with two major lies.

This slide shows the amount of road violence in the HRM per capita. In his presentation to the committee, MacIntyre told everyone that 2020 was an outlier and that the city is choosing to use per capita as a metric, making it easy to compare ourselves to other cities.

While 2020 is an outlier in that it’s unrealistic to lock everyone down to increase road safety, it shows that it is possible to reduce road violence massively by limiting the amount of car traffic on the roads. Thanks to the per capita reporting metric, we know that removing cars from the road in 2020 has also been the year with the least per capita road violence in the HRM.

There are many issues with the per capita reporting metric. Still, one of the benefits, according to staff, is that it allows for equivalent comparisons to other cities or previous years in the HRM. Since other cities also report their automotive death and maimings in per capita metrics, our city staff can pay attention to other cities, and if they achieve a per capita drop, we can steal some of what they do.

Which would be fine if we used per capita numbers this way, but we do not. For example, for the past seven years, the town of Hoboken, New Jersey, has achieved a per capita number of zero road deaths. How did they manage not to kill anyone on public infrastructure for the past seven years? On top of making roads harder to drive and safer for non-drivers, the big thing they did was get rid of parking to reduce the number of drivers in the city overall. Reducing the number of drivers and making driving harder (i.e. narrower streets force drivers to slow down) has resulted in zero deaths for the past seven years. Even though Hoboken is much smaller than the HRM, we use per capita to make a one-for-one comparison with other places. Instead, HRM’s traffic staff like MacIntyre and director of traffic management Lucas Pitts point to cities worldwide where the per capita numbers are increasing. This is a very important move politically for the traffic engineering profession as it allows people to continue to get injured and killed on HRM’s roads, and as long as other places are doing worse, we can continue to claim victories in road safety.

Moving on.

Slide two is jargon that means nothing.

Slide three lays out the city’s new vision and goal. The issue with the city’s vision being zero deaths but measuring progress per capita is this: If Canada is experiencing a huge population spike, which we are, then it’s possible for that population growth to mask an increase in violence. Last year, 2023, there were six deaths on Halifax’s roads. If another six people die this year, because our population has gone up, this will be seen as a road safety win by the HRM because the per capita number will have gone down. Cool.

As an aside, this was also brought up at the transportation standing committee meeting on April 25. In response to the above criticism, Pitts demonstrated that he does not understand how strategic plans work. He revealed himself as unfit to head the HRM’s road safety framework’s implementation when he said, “We are not necessarily tied to the per capita piece, uh absolute works just as fine.”

An absolute metric will not be “just as fine.” Using an absolute metric requires a plan that tries to prevent road violence. This plan is a political communications document with road safety decorations. We had a plan with a goal of an absolute reduction in violence in 2018. The 2018 Strategic Road Safety Framework laid out that drivers are responsible for all road violence due to malice, inattention or bad engineering. To prevent the danger of drivers, we need to reduce the number of drivers on HRM’s roads by making massive changes to how we move around. We didn’t do that, because we don’t want to change how people move around. So we failed in our absolute goal. Instead of changing the plan to change how we move, we instead changed to the per capita reporting metric to hide our failure to change the way people move. It’s honestly terrifying that Pitts doesn’t understand why an absolute goal with this plan would not be “just as fine.”

Moving on.

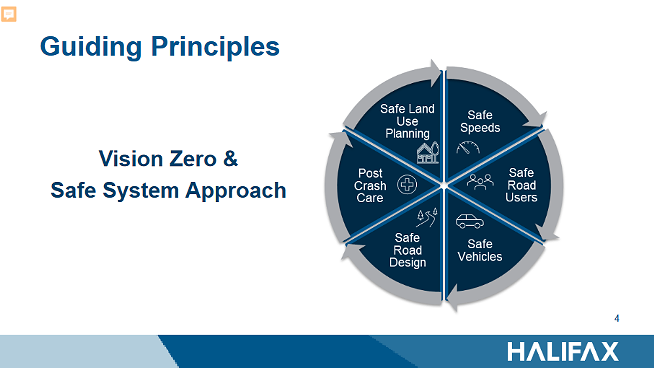

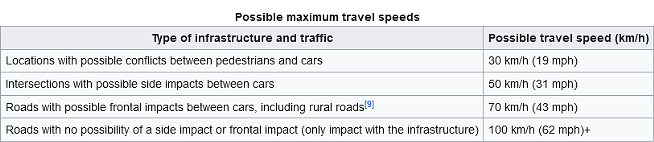

This slide's issue is that it allows HRM’s traffic engineers to perpetuate the lie that the province is responsible for setting speed limits. This is a little in the weeds, but the province is only responsible for setting the posted speed limit. Over the past year, provincial spokespeople have confirmed multiple times that the posted speed they put up is based on the speed at which the road is designed. This means every time HRM traffic engineers tell councillors that the province won’t lower the speed on a street, what they should instead be saying is that they (or their predecessors) designed a street that was too fast for the desired slower speed so the street design needs to be changed.

So every time a traffic engineer says, “The province won’t let us lower the speed” instead of “The province won’t let us lower the speed because we designed this street for quick car commutes,” they are lying by omission.

This lie is even more infuriating if you have a basic understanding of the HRM Charter and know that land use and road design are the only two places where our municipal government’s power to enact change is absolute.

Moving on.

If this were a real strategic plan that followed the Vision Zero philosophy, when city staff say intersections are a top priority, there would be a list of guidelines and criteria to make intersections throughout the HRM safer in accordance with Vision Zero guidelines, which are as follows:

But because this is a bad plan, when staff say intersections are a priority, they mean they will come back to council with a plan to improve Halifax’s 10 worst intersections.

And when they say vulnerable road users are a priority, they lie. Ignoring that using the term “vulnerable road users” implies that driving road users are the norm, our city is just not interested in protecting people who bike or walk around this city. We could do things like put in bike lanes or bollards, but these measures are usually dismissed because it would make snow removal challenging. While this is true, what this means in practice is that a quick car commute on the approximately 12 days a year when we get more than 5cm of snow is more important than protecting tax-paying pedestrians or bike riders for the remaining 353 days of the year.

Here’s a fun fact about Halifax’s road safety stats. Did you know that in 2023, 100% of the 5,206 collisions on HRM roads were caused by drivers? If protecting people from these dangerous road users was actually a priority, we’d be building infrastructure to protect walkers and bike riders from drivers. And drivers from each other. Instead, we build infrastructure to make it easier for dangerous road users to drive around in the snow.

As a tangential aside, one of the benefits of contracting out snow removal (or any public good) to private companies is that they are supposed to be more adaptable than the government. The above “we can’t build bollards due to snow removal” exposes one of the fundamental lies of public-private partnerships. If changing our infrastructure means that we won’t be able to hire private companies because they won’t be able to adapt, then one of the supposed benefits of P3 contracting, the adaptability of the private sector, is a lie.

Moving on.

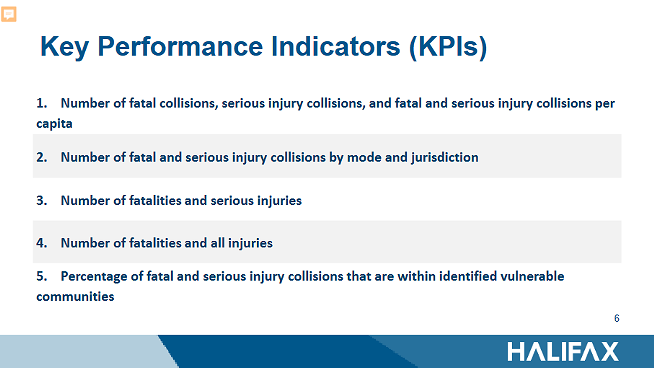

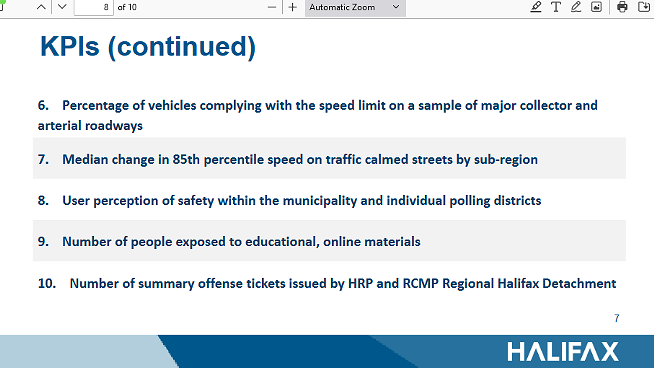

We’re not going to spend too much time on the Key Performance Indicators, but there are two things worth mentioning. The first is that the number of tickets cops issue is not a measure of road safety. There are too many missing variables, like how many tickets should have been given but weren’t, for tickets to accurately reflect road safety.

The second is the city’s continued use of the 85th percentile speed as an acceptable safety standard.

The 85th percentile speed is a metric traffic engineers accept as fatal flaws in their designs. For example, when assessing a street for the HRM’s traffic calming program, a street will be eligible if 85% of drivers are speeding. Once the traffic calming is done, if 85% of the drivers are no longer speeding, then traffic calming is considered successful. However, this means that city staff will try to reduce the risk of preventable injury and death to 15%, call it a success, and then measure per capita to prove their fatal failures are safe.

The 85th percentile speed metric has no place in a vision zero document. It’s not “vision 15% of road deaths are acceptable.” It’s vision zero.

Moving on.

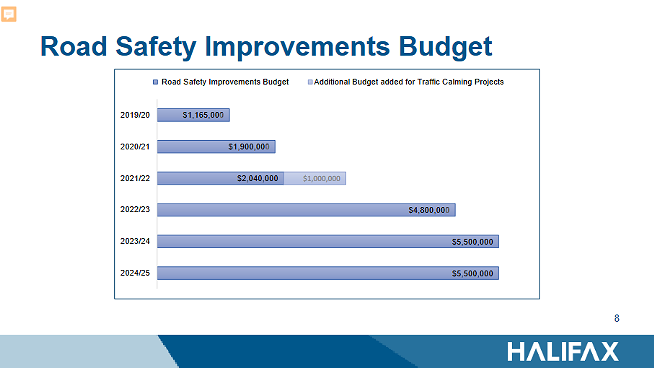

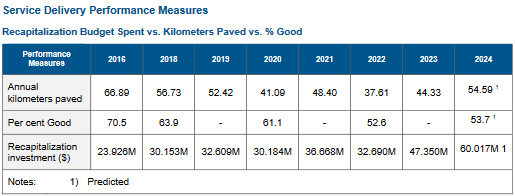

At the start of budget season last year, many of our municipal politicians from Lisa Blackburn to Mike Savage referenced one of Joe Biden’s favourite anecdotes: “Show me your budget, and I’ll show you what you value.” While $5.5 million may seem like a lot of money, it’s about 0.5% of Halifax’s overall budget. That gets even more insignificant when you factor in that $3.5 million of that spending goes to HRM’s traffic calming initiatives. This means some of that money is spent on things that make everyone safer, like narrowing intersections, and some of that money is spent on speed bumps, which only serve to make drivers 85% safer.

Even if we spent the whole $5.5 million on things that made everyone safer, like bike lanes, it would pale in comparison to our road spending. If we spent that $5.5 million on roads, it would cover the cost of paving approximately five kilometres of road. Because we value car traffic and road death, this year we’re spending $60 million to pave just less than 55km of road.

Ultimately Halifax’s new Road “Safety” 😉 Framework will be heading back to the transportation standing committee unchanged and this whole process taught us citizens a few key lessons about our municipal democracy.

The first is that the active transportation advisory committee serves no practical purpose for existing in the HRM’s democratic processes. Either because its members didn’t see any issues with this strategic plan, or because members of the committee like Peter Zimmer and Douglas Wetmore provided feedback to staff that highlighted some of the issues outlined in this piece. We can hold our breath, but after we pass out and their suggestions are not incorporated by HRM staff when this comes back to the transportation standing committee, it begs the question: what’s the point of this advisory committee’s existence?

The second is that traffic engineers like Pitts and MacIntyre can not be trusted with planning a safer transportation future for the HRM. While traffic engineers should play a vital role in managing car traffic as we transition to a low-car future, they have proven themselves incapable of even imagining a world in which Haligonians drive less. So how can they be trusted to plan for something they can’t even imagine?

The third is that this is an absolutely terrible strategic plan that will never achieve the goal of vision zero for all of the reasons laid out in this piece. In spite of this, at the advisory committee meeting, councillor Patty Cuttell called this new framework a good “step forward.” She has not responded to an interview request to explain why she thinks this. In April councillor Waye Mason said he thinks this plan is “really good work,” and at the same meeting councillor Shawn Cleary called this a “great plan.”

To be fair, if councillors want to maintain the status quo and mitigate as much danger as possible without fundamentally changing any of the systemic issues that make driving so deadly, then this plan is fine. But if councillors want to actually make roads safer or achieve the goals of the Integrated Mobility Plan or HalifACT, then this plan is absolutely horrendous as it fundamentally undermines both.

On a practical level, because this is an election year, if you are a voter that cares about preventing the ongoing climate emergency, or having no one die a preventable death on infrastructure you pay for, you can’t cast your ballot for any councillor who votes in favour of this new road safety framework. If councillors Trish Purdy, Waye Mason, Shawn Cleary, Patty Cuttell, Pam Lovelace, or Tim Outhit vote in favour of this motion in June, they are demonstrating that they do not have the skillset or leadership we require of our elected leaders in a climate emergency.

It means they are unfit to hold office, and you will need to vote accordingly in October.