After the annual elections of the chair and vice-chair, Halifax’s Board of Police Commissioners used its Monday, Jan. 8 meeting to vote to recommend council approve an additional six RCMP officers in the 2024/25 budget: two for domestic violence, four for general duty.

After commissioner Becky Kent kept her seat as chair and vice chair changed from commissioner Harry Critchley to Gavin Giles, RCMP top cop stand-in-spector Jeff Mitchell gave a brief presentation to the board about the RCMP. In the presentation, Mitchell said that he needed more officers in general duty so that policing could be sustainable.

But as the board learned later in the meeting, policing won’t be sustainable until the job of police is well-defined. Right now, the RCMP are using their limited-to-the-point-of-needing-more-officers resources by doing data collection in the domestic refugee camps in their jurisdiction. Inspector Mitchell told the board that most of the people in the camps are normal people in desperate circumstances. Circumstances, it should be noted, that are created by political failures at all levels of government. And since that failure continues unabated, these camps of despair are fertile ground for bad actors looking to exploit the suffering of others for personal gain. It should also be noted that Mitchell repeatedly stressed those bad actors are the exception, not the norm. He told the board that most of the people in the camps are normal, if desperate, Haligonians. He lamented that those bad actors shaped the stereotypes the general public seems to hold of encampments.

Commissioner Yemi Akindoju asked if anyone was collecting data on people in the camp. He wanted to make sure the city knew what the people in the camps needed, and why they were there. These two pieces of information are vital to any policy maker or government looking to seriously address the underlying causes of poverty. The RCMP told the board that they were collecting this type of information for the federal Homeless Individuals and Families Information System database—HIFIS—but were running into some road blocks. Mitchell told the board RCMP outreach officers were having some trouble collecting this information because some of those vulnerable people were hesitant to cooperate with “the state.”

This could have been an excellent opportunity for a city serious about police reform or fiscal responsibility to have two pretty major debates about the future of policing in this city. Because it should be obvious to anyone that keeping track of the human beings living outside in poverty in one of the richest countries of the world should not be the job of the police.

The first debate should have been around the role of the police. As it stands right now, the police’s main job is to catch “bad guys.” This is why they have fast cars, guns and handcuffs. It’s why we sometimes think it’s a good idea to buy them an armoured personnel carrier, like any modern mechanized infantry force should have. We gear and train our police officers for the role they *should* be playing in society. They should be involved in a very small part of our growing refugee populations—catching the bad actors.

The city has a municipal team dealing with housing and homelessness, currently being led by Max Chauvin. His work is being folded into the about-to-be-stood-up community safety business unit led by Amy Sciliano. Is this administrative task of keeping track of and caring for Halifax’s capitalism refugees best done by the department with guns? Or should it be done by the ones with wrap around healthcare services? According to a city spokesperson, the community safety department is looking to use HIFIS, but so far there is no timeline for implementation.

The other thing the board didn’t seem to recognize as important information for them to act on is the idea some people in camps don’t feel comfortable sharing information with the police. Because that reason is, more often than not, the people in encampments are painted as the “bad guys” police are tasked with catching.

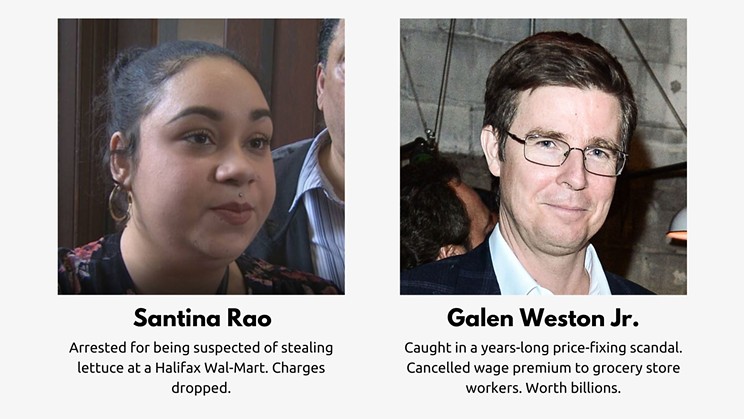

For example, there is a man in Canada who is profiting of the hunger of millions of Canadians. As food bank use spikes faster than grocery profits, our federal political leaders choose performative bullshit and asking nicely over strong anti-trust legislation. Our governments have given him millions in direct subsidies to his already profitable business. And even when we catch him fixing the price of bread, which is a crime, so far the punishment has been to give the victims money to spend at his store and a $50 million dollar fine, which is pocket change for a company that saw revenues last quarter of “$18,265 million, an increase of $877 million, or 5.0%.” Meanwhile, locally in Halifax we use municipal resources to prevent people from stealing food. Hell, cops might beat you up if they think you may have stolen lettuce. We are asking people to trust a system that does not seem to be fair, at the same time we are asking them to trust police who—as an institution—are asked to both punish people for being hungry and administer to the needs of people when they are hungry. The police can’t be both. It is unfair to the officers and the unhoused to expect the police to be both.

Commissioner Kent closed the meeting by lauding the police for their tireless, unsustainable, efforts to be both.