Changing leaves and a crispness to the air are just around the corner. But the arrival of autumn brings more than the return of pumpkin spice and apple picking. After taking a break during the hotter months, ticks are back on the scene.

We’ll start seeing a lot more ticks once the weather begins to cool down in September, and they’ll be around until November, says Vett Lloyd, researcher and director of the Lloyd Tick Lab at Mount Allison University in Sackville, NB. The difference between the tick seasons is that in spring, it’s hungry adults that have overwintered that are out and about, and they’re bigger and easier to see, Lloyd explains. “In the fall, we have some adults who've managed to get to the adult stage and they'd like a nice blood meal to take them through the winter. Plus, we get the immature juvenile stages, which are equally hungry, but the bad news there is they're smaller and harder to see,” she says. “There are ticks out, essentially. There is no difference.”

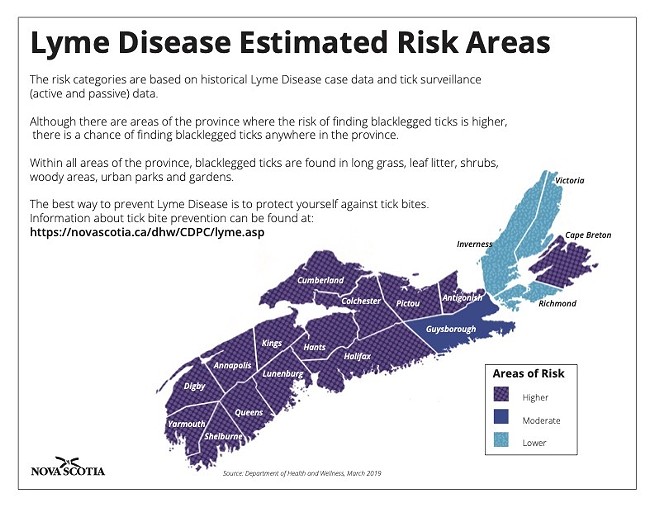

“Everywhere in Nova Scotia is bad for ticks”

Nova Scotia has the second-highest number of ticks in Canada (behind Ontario), and the highest tick-to-human ratio. Ticks love our province’s warm and humid climate, and there’s lots of their favourite food here: Mice, deer and coyotes. The province is home to several varieties of ticks, but the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick, is the one that carries the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. Blacklegged ticks first appeared along the South Shore, and have spread across the province over the years. “So pretty much everywhere in Nova Scotia is bad for ticks, and bad for Lyme disease,” Lloyd says. The epicenter of Lyme disease-carrying ticks is in the South Shore and New Glasgow areas, where around 40% of blacklegged ticks carry the bacteria, she says. The rate is lower in other regions, but “what matters to people is you've got a tick on your leg, you don't care what the provincial average is.”

And the tick population is on the rise, Lloyd says. A big factor is climate change. “Whenever a female can get a nice full blood meal she can then lay about 3,000 eggs,” she explains, “so that means the population could go up and up very quickly. In the past, the cold winters have killed off a lot of the the young ticks because they're a bit delicate, but the winters aren't as cold, the snowpack isn't as deep, and so more of those babies are surviving to get their own blood meal and make their own 3,000-odd ticks.” There are other reasons too, like changes in our food habits. We eat a lot less deer than we did 100 years ago, so now there are a lot more deer for ticks to feed on, Lloyd says.

Naturally, more ticks means more ticks with Lyme disease. The parasites aren’t born with the bacteria, they pick it up from animals like wild mice, which are their main food source, Lloyd says. “If that mouse is infected, the tick becomes infected, and then it can pass it on to the next host—so as things go on, the infected ticks will infect more mice, those more mice will infect more ticks, so it snowballs. And that’s what's happening.”

How to protect yourself

If you plan on taking lots of autumn hikes, the number one precaution you should take is routine tick checks, Lloyd says. At the end of the day, just like brushing your teeth, you should stand in front of a mirror “and you're checking your entire body very carefully for things that look like moles, but have legs attached. The moment you see legs, it's not a mole anymore,” she says.

“Don't expect them to be flashing lights and great big things. Check every nook and cranny,” Lloyd says. On kids, ticks are usually found around the hairline, while on adults, they tend to be lower on the body. “They climb up to warm dark places. So that means adults are gonna have to start looking at bits that you wouldn't normally look at, but that's the way it goes,” she says. There are some commercially available tick repellants, and mosquito repellant is “somewhat effective.” You can also cover your body while outdoors, by tucking your pants into your socks for example. One precaution people absolutely should not take, Lloyd says, is staying inside. “We live in a beautiful part of the world. So absolutely, people should go for a hike.”

If you do find a tick, get it off of you. “There's a little bit of mystique about the do's and don'ts of removing a tick, but probably the important thing to remember is removing it. Don't spend oodles of time googling how to do it. If you get it out of you, good.” (To save you the googling, use tweezers and pull slowly and carefully from as close to the skin as possible. Do not squeeze or twist the tick.) It’s important to catch the tick early, within 24 hours of the bite, when your risk of infection will be the lowest. If the tick has been feeding for longer, or you get it tested and know it’s infected, Lloyd recommends seeing a doctor to get a two-week course of antibiotics: “That will be preventative, as long as you're catching it early.” You can send your tick in for Lyme disease testing, but it’s a private service. “People have to pay for it which kind of sucks. Well, it does suck, but pun not intended,” Lloyd says.

Monitor your symptoms after a tick bite and watch for a fever, headache, tiredness, joint pain or a rash. Lloyd says not everybody will get a rash when Lyme disease kicks in, and you might think you have a cold or COVID. So it’s important to pay attention. “Once Lyme disease is present in your body, the bacteria that are going to spread around your body are going to get lodged in different organs and that's when the real damage starts. So one wants to avoid that. So preventatives like bug spray, like religiously checking yourself for ticks. Paying attention to fevers because fevers mean something’s wrong,” Lloyd says.

What’s going on in tick research?

Lloyd says given the number of people who are impacted by Lyme disease, it’s very under-researched and underfunded. “I think that's a historical glitch, because it's traditionally been treated as just a mild disease, taking antibiotics for a day or two, or maybe a week, and you'll be fine. And what we're realizing now is, it is a very serious disease—once it gets into your major organs, it's debilitating,” she says.

Like many other tick researchers, Lloyd started working on them after contracting a tick-borne disease. She was bit while gardening 10 years ago. “Ticks were not officially present in New Brunswick at the time, but I do live on the border with Nova Scotia. And so that was just a policy thing. The tics were unaware that there was a provincial boundary there and that they were supposed to stop at the border,” she says. Lloyd converted her lab, which used to study cancer, to one that studies the far-less-researched tick-borne diseases. “The state of knowledge did not prevent me from getting sick, and didn't help me get better until I kept fighting for it,” Lloyd says. “And I wanted to do what I can to help. That was a decade ago, and I’m still trying.”

Lloyd is currently researching variants of Lyme disease and other pathogens, such as anaplasmosis, that can be found in ticks. “Nova Scotia is at the forefront of new pathogens that are coming in that we're finding in ticks. So congratulations to Nova Scotia for being at the cutting edge of new pathogens in ticks,” she says. “And hopefully health-care providers will be somewhat aware that they don't just have to worry about Lyme disease when someone comes in with a tick bite.”

On the medical side, the current diagnostic regime has barely changed since the ’80s and ’90s, so Lloyd hopes that will improve as people realize how serious Lyme disease is “We can do better than that. And it's about time to do that,” she says. Her lab used to test ticks for free, but the funding for that ran dry. With more testing and a more precise diagnostic regime, she wants to see health care more specific to people’s needs.

Across the border, an exciting development in tick research is happening in the form of a Lyme disease vaccine for wild mice. “If they're not able to have the Lyme disease bacteria, we still have ticks but they're not transmitting disease. That's a step up,” Lloyd says.

Lloyd says Nova Scotians are generally well informed about ticks, but our health-care system can be a barrier when it comes to proper treatment. “The health-care system is struggling. So if they're struggling to deal with heart attacks and people with chainsaw injuries, a tick bite may not seem that serious, but it still has to be dealt with.”

More tick resources

- eTick is a free online tool that can identify ticks and includes an interactive map of tick sightings.

- The government of Nova Scotia’s tick safety page

- The Nova Scotia Health Authority’s Lyme disease pamphlet