Act one: A change in shape

Our story begins against the backdrop of a global pandemic, set during a year so unprecedentedly strange, the vernacular to discuss it is still being ironed out. Our protagonist, the hero of this tale, isn’t exactly a protagonist at all—or at least isn’t a person. It’s the oldest art form, which has stayed relevant across civilizations; which has lasted throughout the rise of television and waited out its time during the age of the internet.

Our hero is theatre itself. And these days, it’s going through its most epic saga yet. How will our warrior fare throughout these uncertain times ahead?

See, in Halifax, a play is bodies crushed into bleachers at The Bus Stop, collectively contributing to a world-building-in-progress. It’s a soliloquy spoken over a summer sunset in Point Pleasant Park.

It’s the glamour and pomp of being shown to your seat at Neptune Theatre, awaiting the velvet curtains drawing back.

In Halifax, a play can also be an app. It can be you Waiting for Godot to join your Zoom call. It can be a package of poetry mailed to your door that you read—perhaps while making your own unboxing video. It’s a drag show filled with projected visuals, streamed live through your phone. It’s a show tune sing-along on TikTok.

But when about the first half of this list disappeared (at least for now) last March, it could have been a death knell. A fatal diagnosis. The final, mournful notes and the quiet that comes after. A fade to black.

Yes, when COVID-19 came, it could have been the end of theatre in Halifax.

After all, without the ability to gather dozens of bodies in a room and bring a story to life—without the ability to form crowds or audiences or even a full cast—what was left? What would there be without the structure of stage and spectators?

It turns out, there’d be a whole lot.

“Theatre is, to me, live storytelling,” explains Aaron Collier, the technical director of HEIST live art company. “Where the set and the setting are part of the story and considered.” He should know: with HEIST, he and his fellow show creators have birthed a catalogue of award-winning, genre-flouting performance, building a glitter-encrusted bridge between Halifax’s theatre and drag communities along the way.

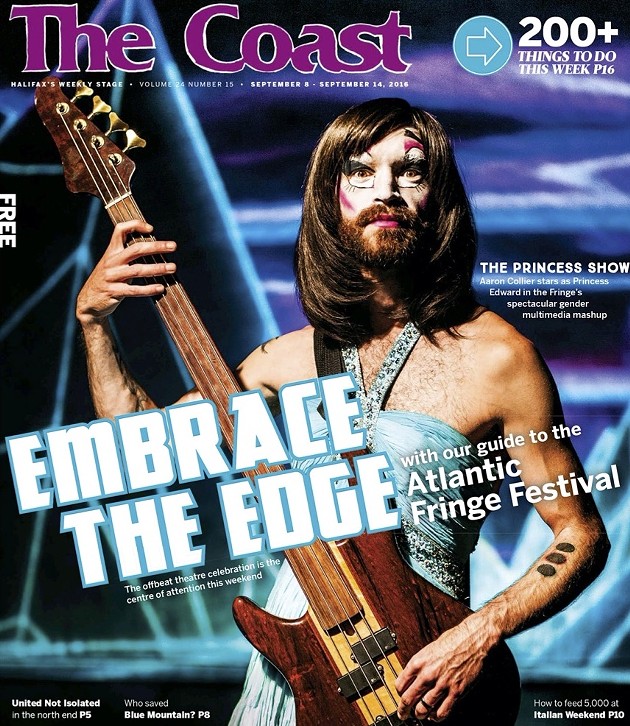

This is showcased in the company’s 2016 debut, The Princess Show, which went on to become the buzziest play at that year’s Fringe Festival (where it also won the Best of The Fest award) and its follow-up The Princess Rules, which picked up in 2017 where Show left off—but with HEIST returning with a larger crew and larger spectacle. (“We've levelled up a bit," Collier, standing outside of the now-gone Waiting Room on Almon Street, told The Coast back then. "It's like we went from Nintendo to Super Nintendo.”) Both stories swirl around the titular Princess Edward, royalty who uses a mix of genderfuck drag, anime and claymation to take the audience along on her epic saga.

It’s also present in HEIST’s Takeovers, ticketed parties featuring performances by Halifax drag performers and games like Lip Sync Roulette. (In the era of Covid, these gatherings have slipped online frictionlessly: “It’s like a party in a Zoom room,” says Collier.)

"We thought 'maybe there’s something in this'. So now here we are, trying to discover if there’s something in this.

tweet this

During the pandemic, HEIST’s technology-doused , multi-media approach has grown even stronger with the show Frequencies (Phase IV), a multi-perspective storytelling show staged for a small in-person crowd and a larger audience tuning in online: “I think in this way, we’re doing the same thing in a format that certainly is new to us—but in the end it’s still the same thing: We’re doing storytelling, we’re doing it live, it’s ephemeral. And I think it does change, depending on who’s tuned in,” says Collier, by way of explaining what the August 22 show would entail.

Speaking by phone hours before showtime, he adds: “We had already invested a significant amount of our time and energy into figuring out how to make sort of 3D digital worlds and sort of these fantasy drag performances in the digital domain, so at that point…we thought maybe there’s something in this. So now here we are, trying to discover if there’s something in this.

“Engaging people this way, your audience is no longer whoever who can come to Parrsboro to see the show but it’s everybody who’s awake on earth that you could possibly get your attention,” he adds—continuing the vibe that for theatre in Halifax, a new challenge is a new chance to shine.

Eventually, Frequencies will become something closer to the in-person show that’s “one part confessional, one part TED Talk-style presentation and one part techno-songwriter concert,” a pre-Covid press release promised for what should have been its June 4-7 run at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium. (Collier thinks it'll be shown in February 2021 at The Bus Stop.)

But until then, perhaps the fact that some folks met the project this way first is actually better: “In a standard sense, I would beam these images out of projectors and I’d play these sounds through speakers and if I wanted to bring the show around, I’d drive or have to fly,” Collier says. “Whereas this, it almost feels more direct or more pure in a way: because I make music and visuals inside computers, at this point I’m beaming straight out of the computer right to someone else’s screen and there’s a kind of directness in that way.”

The idea of another world being built not only in script but also in multimedia is one that’s also followed Halifax’s all-woman collective The New Pants Project since its 2019 beginnings. Last fall, when the collective made its debut with How The Light Lies (On You)—a play charting the successes and failures of 20th century painter Florine Stettheimer—its set design immediately struck the eye, rife with projected artwork that fell across the actors’ changing facial expressions, and cellophane art that added another dimension to a moving study of a woman’s life’s work.

“It's an interesting way to know her life. You can read a Wikipedia article about her, you can look at other profiles about her. It's another interpretation of her life based on her art,” the show’s scriptwriter, Edie Reaney Chunn, told The Coast last August.

Last month, NPP took its adoration and excavation of Stettheimer’s life a step further with its play from:Florine.

“We started out calling it a prescription poetry project,” explains show co-creator

and co-producer Kirsten Bruce, on a group call with co-creator and co-producer Anna Shepard. The final product, billed as an “interactive-immersive-multimedia-mailout-performance-art-piece,” according to its website, saw would-be audience members receive a piece of personalized poetry by mail, which they would open in advance of a live “salon,” where the actors and letter-getters could bask in Stettheimer’s words together, in real time via YouTube (you can also watch a recording of the performance here).

The show—part of this summer’s online-only edition of Eastern Front Theatre’s Stages Festival—was built for a pandemic where people were starved of live performance. “We were all sort of frustrated with the easy replacement of a film medium for theatrical medium. One of the things that’s really special about theatre to us is its liveness and the feeling of connection between the artist and the individual,” Shepard says.

And what, exactly, makes a poetry mail-out and live Zoom afterparty count as theatre, anyway? Well, think of it as she does: “Theatre is the moment of live exchange between artist and audience—it’s really the opening of the letter that’s the moment of theatre,” Shepard says. “It’s being able to witness and be witnessed.”

Act two: An idea takes root

Ours is a hero that has weathered the storm. Not an Achilles, waiting around on the beach, but rather an Odysseus, charting a path on stormy waters without a map. It relies on creativity and passion, and doesn’t fall for the siren call of waiting for an easier route.

“To be honest, I think in the theatre world we have a pretty unhealthy attachment to the phrase ‘the show must go on,’” Lee-Anne Poole, executive director of Halifax Fringe, told The Coast on September 1 in a story announcing the festival’s 2020 against-all-odds return. “Like, someone could get the worst news of their life and that actor would still go on stage that night.” (Indeed, Fringe is back for the entire month of September, with scads of socially distant and online programming.)

Poole’s right. But this sentiment also belies a hunger, a need for live art that lives in both audience and performer alike. Back in mid-March, we didn’t know when the show would go on again. But that hunger, already roaring, took over. Halifax’s theatre community got to work. It became clear that the pre-existing creativity of the indie theatre community would be what saw the genre through this—and what would see audiences through, too.

“What theatre was 2,000 years ago is not what it is now, is not what it was 1,000 years ago. But I do look forward to a time we’re making a piece and we can have people in the same space together.”

tweet this

It’s here, in this moment of a million wild seeds embedding themselves in the minds of Halifax playwrights, that we see what possibility can sprout into: Maybe it’s time to stop asking what can be a play and, like these dramaturgists, scriptwriters and directors, start asking what can’t be.

That’s how Alex McLean, co-artistic director of Zuppa Theatre, explains the creation process of what is possibly the city’s most boundary-pushing maker of live performance. “It’s kind of what we’ve always done: ‘well what if this’ and ‘well what if that’ and just follow where it goes,” he says. “You feel the sparks start to fly and you know you’re making something exciting.”

Throughout the pandemic of 2020, Zuppa has kept busy: One of the first theatre companies to return from the void’s edge, it launched Vista20 while the rest of us were trying to decide if pushing an event to October was a sure bet or wishful thinking. Billed as a walking tour that you could take around town or your apartment, it compiled recordings of the stories of health care workers on the front lines during the lockdown’s first legs.

“It tries to give you space to think,” McLean said to The Coast around the time of the play-dressed-as-an-app’s initial launch. “It’s meant to be this personal thing where you can reflect on your own. You have this moment to listen to other people’s thoughts and have your own.”

It was a groundbreaking idea, one in step with Zuppa’s larger resume. (This is the theatre company, after all, that once made a play that was just you, listening to headphones inside a library, called The Archive of Missing Things. It’s the selfsame one that built an intricate web of live vignettes to experience while walking around town with This Is Nowhere in 2018.)

But, in a classic Zuppa move, this was just the beginning: Earlier this month, the company launched a second walking tour app (a play without actors, set or script), titled Labour7. Still finding ample inspiration in our current times, this piece—that yes, you can download in the App Store and on Google Play, along with Vista20—is “a snapshot of labour in the age of COVID-19,” as McLean puts it.

“It’s like a podcast in a way,” adds Stewart Legere, Zuppa’s associate artistic director, on the same Zoom call.”You’re hearing people tell their stories—but we’ve made it through our lens, which is we’re performers and we’re theatre people who’ve spent our lives creating experiences in rooms together. So, even though this is not that, there is a filter it goes through through us and our collaborators that flavours it.”

Both can’t wait for the return of conventional theatre (it feels like a constant strain and creak of the heart to have to wait until 2021 for Neptune’s doors to reopen), but both can’t imagine any end to their plays playing dress-up in other forms’ clothes.

Says McLean: “What theatre was 2,000 years ago is not what it is now, is not what it was 1,000 years ago—it’s an evolving thing. But one thing I do find myself excited about, thinking about the future, is I do look forward to a time we’re making a piece and we can have people in the same space together.”

Act three: An audience is out there

How will our hero be heard amidst the wall of noise that is modern culture? What will make an audience gather in a digital space, when memes and tweet threads and photos with text overlay all hold equal weight on our collective mental timeline?

As theatre continues to be made in alternative ways, how will we know its success? Is it in digital tickets sales? Follower counts? The number of people tuning into an Instagram Live? The number that stay until the Live ends?

“It is live and I know that they’re there,” Collier says of the audience and its influence when talking about Frequencies. But what about when that audience can't be seen? If a play falls in the forest and the actor can’t hear the audience’s applause, was there any applause at all?

These days, Lee-Anne Poole is teaching herself how to use TikTok. The Fringe executive director isn’t necessarily looking to take part in its viral dance crazes, though. Instead, she’s using the bite-sized video-making platform that’s become synonymous with Gen Z to keep the 2020 Fringe Fest alive. First up? Fringe will be taking its annual sing-along stalwart Sing-Along Show Tunez to the platform. Watching host Garry Williams “sing for three minutes at The Bus Stop isn’t too long, but watching it through my phone screen, three minutes is a long time,” Poole muses. She decides to trim the clip—a good move since TikToks clock out at a minute, anyway.

The Fringe Festival—that indie theatre institution, both in name and form—is “like a cockroach,” she tells The Coast. “Even if everyone who produces it now suddenly moved away and didn’t want to do it again, next September what would happen is a Fringe Festival: Like, someone would put it on in the basement of The Bus Stop or whatever, even if the funding was cut.”

No stranger to making something of nothing, Fringe has adapted to many a challenge, from disappearing venues to this, the season of no venues at all. What does that look like for the festival itself? Plays being performed via Zoom and Instagram Live. One-person shows you can listen to on Bandcamp. Outdoor, physically distant setups for improv and children’s theatre. There’s even a Fringe play taking a leaf from Zuppa’s book and making a walking tour. (This one—called Dispatch—guides you “through a cityscape you thought you knew” by texting you clues to decipher and puzzles to solve, explains its online ticket page.)

“We’ve been super lucky: We’ve got an awesome and interesting and interested community of people that follow our work and that’s kind of the only way that we can do it,” says Zuppa’s Legere, days later by phone.“How are the million ways that we could try use technology so that a show is super fulfilling, super connective? And I don’t think we’re even close to figuring that out, that we’re ending that journey anytime soon.”

“It makes me think that the moment of theatre is actually just possibility,” Poole says. “Last week, I was at The Bus Stop because we were doing audio recordings of somebody's podcast. And Matt the technician was setting up a light, and I was standing just in that room painted black with just one theatre light on. And it was dark in a way that it felt like there could have been an audience in the room. There could have been 70 other people in the room. And I was standing onstage alone. And for a second, the air felt more thick with possibility.”