Wages are not an issue in the contract negotiations. The city has offered a 0.5 percent wage increase for this year---for a conventional bus driver, that's a raise of just 12 cents an hour from the existing $24/hour to $24.12/hour. That pay rate would apply to all drivers, no matter how long they've worked for the company; a 30-year veteran makes the same as someone who's been driving for one year.

A similar wage increase of 0.5% has been offered for all transit workers, including ferry operators, Access-A-Bus drivers and mechanics. The city's offer for the second year of the contract is an across-the-board pay increase of 3.5 percent.

The city's offer is for just a two-year contract, retroactive to the expiration of the last contract in September; past contracts have typically been for four years, and once for six years. That means if the union agrees to it, as soon as the ink is dry on the contract, the two sides will start negotiating for the next contract.

Still the union is willing to accept the poor wage offer. “What is the point of striking over wages in 2012?" asks union president Ken Wilson. " I know the economy’s bad. The state of the economy---everyone’s going through a downturn---we understand that.”

Rather, the union is rejecting three other demands from the city, which roll back existing agreements, some of which have been in place for 40 years. The major sticking points are:

"This union went on strike for six weeks in 1998 for exactly the same article the employer put on the table today," explains Wilson. "Why they think we would change our position on this---it makes no sense at all."

Currently, all transit work is done in-house, unless Metro Transit's work force is insufficient to get the job done. Now, in the city's proposal to the union, the city agrees that "it will not contract out any work that's on the schedule run guide---period," says Wilson. "That means, day one, if we were to sign the contract that was the [city's] final offer, maintenance could be contracted out. Access-A-Bus could be contracted out. Ferry could be contracted out. Maybe the employer reprints the schedule and three months from now removes the #1, #2 and #3 [routes] and contracts them out, because that's no longer in the scheduled run guide."

If Metro Transit can move any job, at any time, over to a contractor, then transit workers have no job security at all. The contracting out clause breaks the union.

But it doesn't even make financial sense, says Wilson.

For example, for the last few months there have been two un-filled "interior wash" positions---employees who used to clean the buses---so not all the buses can be cleaned in house. Wilson claims that management has refused to fill the positions pending resolution of contract negotiations. "Maintenance supervisors tell me that they've done the business case to [city CAO] Richard Butts to hire these two positions, he says no; they do it again a different way, he says no. He keeps saying no. Buses need to be cleaned."

So instead of buses being cleaned in-house, they are being cleaned by an auto detailing company called The Shine Factory, on Akerley Boulevard, about a kilometre from Metro Transit's Burnside bus garage.

According to city spokesperson Shaune MacKinlay, Metro Transit pays The Shine Factory $281.57 to clean one standard 40-foot bus. Wilson estimates the the full costs to Metro Transit for using an employee for cleaning the bus is about $220. Additionally, while The Shine Factory is paid about $60 more, Metro Transit still has to pay a driver to move the bus to Akerley Boulevard and back, incurring additional costs.

Currently, every Metro Transit driver and mechanic is a full-time employee; the city is demanding that the union allow them to hire part-timers.

Using part-timers is a direct threat to the union. As Wilson explains it, Metro Transit workers see their jobs as a career, a secure long-term work situation through which they can reliably pay the mortgage and raise their children. Part-timers won't have that security, and therefore not that investment into the health of the union over the long haul.

But more than that, Wilson warns that it is precisely that lack of job security for job security that will put considerable risk to the public by using part-timers. With no sense that this is his career, that he'll be coming to the same job years into the future, a part-time driver is more likely to lose his cool, to become reckless, to, perhaps, up and leave the bus in the middle of a difficult shift.

Back in 1998, the union opposed management's desire to impose a rule that drivers had to have eight hours off between shifts. "The drivers were a lot older then," explains Wilson, "and more set in their ways; they didn't like change." Wilson was himself a driver, and remembers after driving a late evening shift being ordered to show up for work for the early morning shift, so the change in management demands struck him as odd. Still, "now we like it. We understand that the rule was for safety---drivers need to have a good night's sleep and to be alert on the road. We agree."

The problem with part-timers, he continues, is that there's no regulating what they do off-hours: driving the bus at night might be a second job after working all day at another full-time job, or just one of three or four part-time jobs pieced together to make a living. Without a full-time work-force with regulated time off between shifts, there's no telling how tired or overworked a driver could be, Wilson argues. And this will put the public at risk.

This issue is harder to explain to someone outside the system, but the gist of it is that the drivers' schedule has to change every few months to reflect changes made in routing. For 40 years, this has been the one perk of seniority on the job---the most senior drivers have picked the five shifts they wanted through the week, with less senior drivers choosing from among what's left over, on down the line of seniority to the rookie drivers, who are left taking the least desirable shifts.

Management wants to change this to a block scheduling process: senior drivers will still get first crack at the scheduling, but the shifts will be the same through the week: all eight-hour shifts beginning at 5am, or all split shifts, or whatever. This is a significant change; now a driver can choose to, for example, work two days a week in the evening but the three other days in the morning, so that she can see to the changing schedule of child care needs. The present system is a sort of flex time, while management wants to scrap that.

Wilson says there's no monetary savings in changing the system, but rather management simply doesn't like the hassle of tracking down each of the drivers and coming up with unique schedules.

He does, however, admit that many other transit operations in North America have moved to block scheduling. "It's the Brampton, Ontrario model," he says. "They always point to Brampton. Well, sure, we could move to that---we'll agree to that, if they give us the same wages as Brampton drivers. Pay us $30 an hour."

If there's a concession on the union's part, it'll probably be on this issue. Drivers won't like the change, but neither does it seem to be worth striking over.

It's been 14 years since the six-week 1998 transit strike, and in the intervening years the bus system has grown considerably. Now, the system handles over 90,000 trips a day; businesses rely on Metro Transit to have a reliable workforce, and many workers and students simply have no other option for their daily commute. An extended strike will see traffic mayhem, gridlock on the bridges, a tremendous financial hit to businesses and a poisoning of the goodwill that oils the day-in-day-out functioning of any city.

In short: a strike will be ugly. I don't think the bureaucrats and politicians at city hall fully comprehend the political fireball their attempt to break the union will unleash. I doubt they've even considered it.

For the transit workers, a strike is a desperate measure. They won't get paid, of course; there will be a token strike pay of $100/week but only for those members who show up and work full shifts walking the picket lines. "It basically pays for their coffee," says union vice-president Shane O'Leary.

That union members would even contemplate a strike says something about how they view the city's contract offer; that they voted nearly unanimously---98.4 percent---to strike shows they feel they have no other option. With the contracting out and part-time provisions of the contract offered by the city, the workers see they'll be out of a job soon enough anyway; they may as well take the immediate hit of a loss of pay, in hopes of retaining a career.

Several union members have told me they're anticipating a two-month strike.

The city's demands on the transit union are new kind of management hard ball not seen from city hall before, one that is concurrent with the arrival of new CAO Richard Butts.

The union has said all along that they would work under the provisions of the old contract, which expired in September, and take all the time needed to work out an agreement with the city. It is the city, not the union, that is pushing negotiations up against the wall: the city's negotiators have cut short the negotiating process, and forced the January 22 strike vote with a "take it or leave it" offer not open to compromise.

Butts' strong anti-labour stance reflects the growing divide between workers and managers in western countries, where managers' salaries get ever-bigger, but workers' unions are busted, wages slashed and protections removed.

Halifax council hired Butts last March to fill the vacancy left by the exit of former acting CAO Wayne Anstey. Anstey had made $175,000 annually; Butts was hired in at $285,000, and will see his salary rise next month to $300,000.

A former deputy city manager with the city of Toronto, Butts sill maintains a residence in that city, and word in city circles is that he flies "home" to Toronto each Friday, and returns to Halifax on Monday morning for the work week. Last I checked the property records, Butts owns no real estate in Nova Scotia, and seems to have no long-term personal commitment to the community. Should council want to rid itself of Butts "without cause"---that is, without a finding of wrong-doing---Butts will receive a severance package of $450,000, which he'll presumably take back to Toronto while he looks for his next job.

Workers, however, will receive no such consideration. There are several other city employee unions coming up for negotiating, and Halifax Water workers, who have been without a contract since 2008, may vote to strike as soon as Thursday; their issues are different from the transit workers', but it's worth noting that last year Halifax Water manager Carl Yates got back-to-back annual pay raises of 40 percent---once again, managers' salaries skyrocket, while workers are put against the ropes.

And it's essential that these attacks against workers be seen in the context of the ship building contract recently awarded to Halifax's Irving shipyard. The ships' contract was sold as the route to prosperity for our community, but it appears to be benefitting only a few---for sure, the real estate market is booming, with house prices already jumping six percent. No doubt realtors and property investors are making a bundle. But with proposed salary increases of just 0.5 percent, and with less job security, how are transit workers going to keep up with the additional costs? Heck, even the people actually building the ships--- shipyard workers themselves---are gearing up for a long battle to get even one thin slice of the ships contract prosperity. And the community most directly affected by the increase in housing prices is left reeling, with no assistance given to the community groups that can provide basic support and assistance to the most impoverished.

We are in the midst of an immense re-ordering of our society, a meaner, harsher world, where the rich get much richer, the workers lose what little they had and everyone else can just go screw themselves.

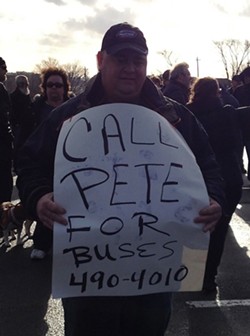

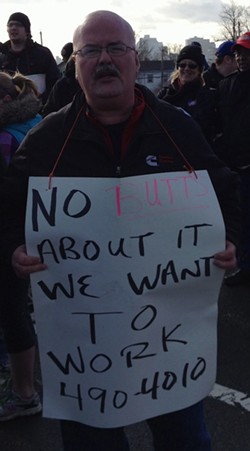

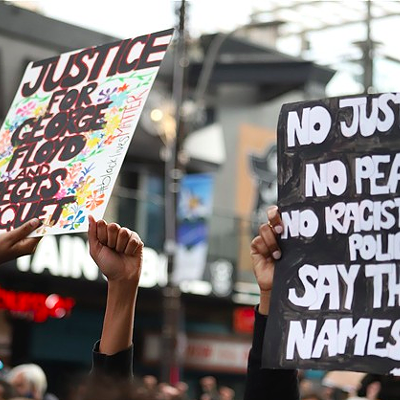

Thankfully, many in the community, and especially other unions, understand the stakes. I've already gone on for much too long, so I'll leave off with some photos from Sunday's rally in support of the transit workers, an audio clip from Rick Clarke, president of the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour and one question: Whose side are you on?

Hear Rick Clarke's speak: