As HRM officials lament the recent Halifax Transit “suck me, boy” racism that, along with a slew of other offences, has earned this town the moniker “

Famed for her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960), details Foster’s role in the peddling of human flesh in Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” The posthumously published narrative was recently hailed by the Washington Post as a “recovered masterpiece that…joins a small body of firsthand accounts of the transatlantic slave trade.”

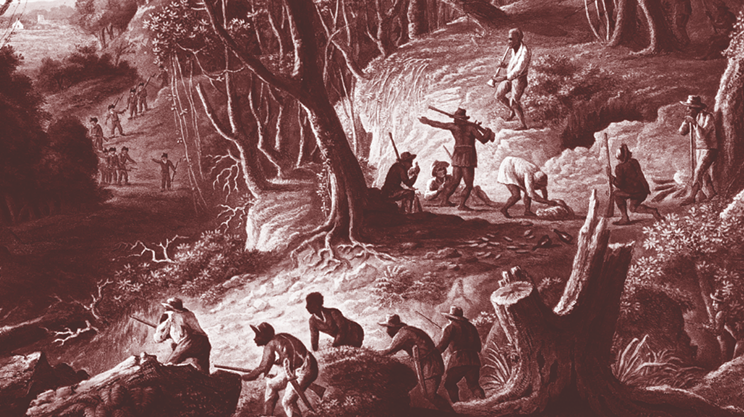

In the late 1920s, Hurston travelled from New York to Alabama where she conducted a series of interviews with Cudjo Lewis. Born Oluale Kossola, circa 1840 in present-day Benin, Lewis was among a group of Africans that Foster, in 1860, loaded aboard the Clotilda, which he’d refurbished to deliver Blacks to auction blocks.

Hurston reveals that Foster, “born in Nova Scotia of English parents,” conspired with a trio of brothers named Meaher to defy an 1808 law that had abolished the trafficking of African peoples to American shores. The

“Captain Foster was associated with [the Meahers] in business and seems to have been the actual owner of the vessel [Clotilda],” Hurston writes. “Perhaps that is the reason he sailed in command.”

As it happened, Foster kept a detailed diary of the voyage, which is today readily available online. Rendered in cursive script, “The Last Slaver from

“Clotilda built…by Captain Wm. Foster, A.D. 1856. Fitted out for the coast of Africa to purchase a cargo of Slaves…First and second mates and

About his arrival on the continent, Foster writes: “I [said] that I had $9,000 in gold and merchandise and wanted to buy a cargo of negroes for which I agreed to pay $100 per head…Having agreeably transacted affairs we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement 4,000 captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me the liberty to select 125 as mine.”

Struck by a rare pang of conscience, Foster notes that he declined an offer to “brand” Lewis and the other Africans as his property.

Upon return to Alabama, Foster nonetheless transferred his “cargo” to a steamboat and hid the captives “until further disposal.” He then burned the Clotilda “to the water’s edge and sunk her,” notes the diary. Their wallets fattened, neither the

Lewis was enslaved on an Alabama plantation until the end of the Civil War. “Freed,” he toiled, under segregation, for the rest of his life. By the time Hurston arrived on his doorstep bearing gifts of peaches and ham, Lewis was the last known person with firsthand knowledge of the barbarity of the slave trade.

Barracoon takes its title from pens where Africans were detained before their forced departure on slave ships. The riveting book features a photo that Hurston took of Lewis during one of her visits. She writes that he dressed in his best suit “but removed his shoes.” Barefoot and tearful, he told the writer that he wanted to look like he was in Africa because that was where he longed to be.

Let the record show that Cudjo Lewis, his life forever changed by a Nova Scotian, died in 1935, 6,000 kilometres from his home and native land.