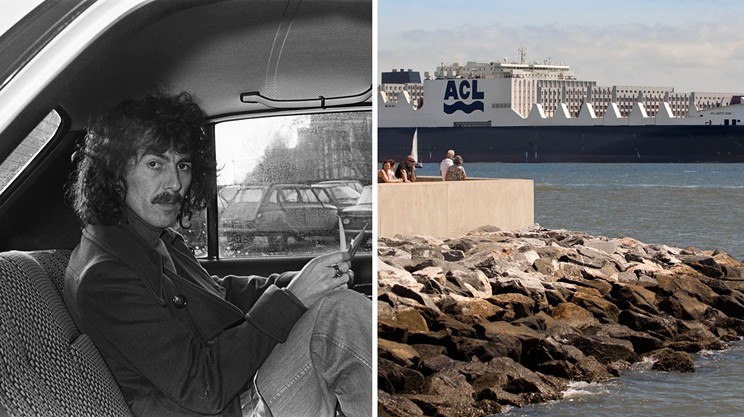

It’s the Tuesday after the first two cruise ships of 2023 have arrived at Halifax’s Pier 20—and for a brief spell, the waterfront is quiet. Waves lap. A seagull drifts in the breeze above the Emigrant statue, a french fry’s toss from where nearly 3,700 cruise ship travellers aboard the Norwegian Dawn and Zaandam filtered through the Halifax Seaport on Saturday and Monday. Signs of another tourist season springing to life abound: Patios are open. Ditto for the gift shops and rental huts advertising chocolates, scooter rentals and “100% authentic British wool.”

For Holly Davy, marketing manager at the Bertossi Group, which owns and operates an array of waterfront bars, restaurants and cafes like The Bicycle Thief, Ristorante a Mano, Bar Sabbia and Pane e Circo, the season’s arrival is a welcome one.

“[We’re] kind of the first stop once they get off the ships,” Davy says, speaking with The Coast from a bar table at The Bicycle Thief.

That enthusiasm isn’t uncommon. According to the Halifax Port Authority, which oversees the arrival of just under 200 cruise ships a year, those ships—and the roughly 325,000 tourists on them—account for roughly $136 million flowing into Halifax and the surrounding area every year. That comes through money spent on tours, in pubs, restaurants, galleries and gift shops, and on ship supplies and provisions when the vessels are in port.

But the industry’s hulking impact is felt in more ways than one: Critics argue cruise ships are not only more carbon-polluting than any other standard form of travel, they’re also an active threat to our oceans and the many species within them. And while other countries have taken strides to mitigate the industry’s effects, Canada’s lax environmental laws are bringing the issue closer to home.

Cruise emissions by the numbers

According to the math of environmental group NABU, a Germany-based non-profit dedicated to “climate protection and energy policy,” for every day a ship the size of Norwegian Cruise Line’s Norwegian Dawn or Holland America Line’s Zaandam is at sea, it will burn through “as much as 150 tonnes of fuel”—and in the process, release as much particulate matter (aerosols, smoke, exhaust fumes and the like) into the atmosphere and surrounding water as a million cars. That spills over into port cities: A 2010 air quality study from Halifax’s coastal peer, Victoria, BC, found that when a cruise ship arrived into port, it raised levels of sulfur dioxide—a compound known to cause lung cancer—more than three kilometres away.

A mid-sized cruise ship with 1,000 to 2,400 passengers will release as much particulate matter in a day as a million cars, environmental group NABU finds.

tweet this

For the largest cruise ships, like the 5,600-passenger Oasis of the Seas that arrives in Halifax on May 31, the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per passenger, per kilometre amounts to more than 10 times that of a trans-Atlantic flight from Halifax to London.

“It makes me laugh when I see ‘no idling’ zones in front of schools,” Merv Ferguson, a retired shipbuilder, writes in an email to The Coast.

“I’ve worked on cruise ship repair. My guess is that 99% of the folks who take these cruises have no idea of the colossal amount of fuels and other oils, greases and hydraulic fluids that these massive engines and associated equipment use in a 24-hour period.”

That is more or less by design: Most passengers book cruises imagining the charming and far-flung port cities they’ll visit—not the after-image those cruises leave behind. (A 2019 “industry outlook” PowerPoint by the world’s largest cruise industry organization, Cruise Lines International Association, finds passengers are looking for “bucket list” items and “setting sights on destinations that were previously out of reach.”) And for what’s visible above-deck in the form of exhaust, more waste passes unseen to most observers in the form of wastewater and greywater dumping. Imagine all of the water used in sinks, toilets, showers, galleys, laundry machines and dishwashers aboard a 2,400-passenger boat: All of that gets released back into the ocean, along with the poop, shampoo, laundry detergents, kitchen grease and other sanitary products that find their way down a drain—a practice that environmentalists caution can lead to low-oxygen “dead zones” and accelerate ocean acidification.

The outcome, Stand.earth shipping campaigner Anna Barford tells The Coast, means the waterways cruise ships travel become “a bit of a toilet bowl … and Canada’s laws will let sewage be dumped pretty well anywhere.”

‘This is not a group that we can really trust’

While Halifax prepares for a potentially record-breaking cruise season—Emily Richardson, a spokesperson for the Port of Halifax, tells The Coast that the port authority is expecting as many as 325,000 visitors on 191 cruise ships from April to November, eclipsing the 323,709 passengers that arrived in 2019—other port cities have begun to turn the passenger ships away. Since Jan. 1, 2022, in an effort to preserve its lagoons, French Polynesia has banned trans-Pacific cruise ships carrying more than 3,500 passengers and capped regional cruise ships at 700 passengers. A year earlier, Italy said “arrivederci” to cruise ships anchoring in Venice’s lagoon after years of protests from residents. And in 2018, citing “overtourism,” Dubrovnik, Croatia capped cruises at two incoming ships per day, carrying a combined 5,000 passengers.

This April to November, Halifax will have 24 days where three cruise ships are in port, two days with four ships in port and one day with five ships in port. According to the Port of Halifax’s cruise schedule, the busiest day of Halifax’s season, Sept. 15, could see upwards of 7,350 passengers arriving within an 13-hour span.

For conservationists like Barford, the passengers aren’t the problem; it’s the cruise lines and their poor environmental records. In 2017, Princess Cruises—which will make 20 port calls in Halifax this year—was convicted and sentenced to five years of probationary sanctions after the company admitted to deliberately dumping oil-contaminated waste from one of its ships—and then trying to cover it up. (The ship in question, the Caribbean Princess, arrives in Halifax on July 31 for its first of nine trips to Nova Scotia.) At the time, the US Department of Justice ordered Princess to pay a $40-million penalty—the “largest-ever for crimes involving deliberate vessel pollution,” the DOJ noted.

In 2017, Princess Cruises admitted to deliberately dumping oil-contaminated waste from one of its vessels—and then trying to cover it up.

tweet this

As part of the penalty, all Carnival cruise ship companies (including Princess Cruises, Holland America Line, Seabourn and Cunard, all of which operate in Halifax) agreed to five years of independent audits, overseen by a court-appointed monitor.

“We are extremely disappointed about the inexcusable actions of our employees,” Princess officials wrote in a statement provided to TravelPulse at the time. “This settlement clearly shows that we fell short on our commitment to the environment, and for this we are very sorry and we take full responsibility.”

Two years later, in 2019, executives at Carnival Corporation (Princess’s parent company) admitted to violating the very probationary terms they’d agreed to—including interfering with court-ordered supervision of its environmental compliance. Then again last year, Princess officials pleaded guilty to yet another violation of their company’s initial probation.

That’s a concern to Barford, who has lobbied for Canada to implement more stringent environmental policies governing cruise ships and their waste.

“This is not a group that we can really trust,” she says, speaking over a video call with The Coast. “They’re not doing the things that they’re legally required to do—even when they’re under a court-ordered probation.”

In an emailed statement provided to The Coast, a Princess Cruises spokesperson calls the company a “cruise industry leader,” committed to “protecting and preserving our precious air, sea and land resources for future generations.” They point to Princess’s recycling initiatives—“on just Discovery Princess alone, the ship recycles nearly 15,000 pounds of glass, 3,300 pounds of cardboard, 8,800 pounds of plastic and 132 gallons of cooking oil each week,” the spokesperson adds—and assert that Princess’ wastewater system “exceeds all applicable wastewater treatment standards for maritime operations.”

A sea change for cruise ships

Changes are coming to the cruise industry—and in some respects, Halifax is at the vanguard of those adjustments. From as far back as 2014, the Port of Halifax has offered shore power, which grants cruise vessels the ability to plug into the port’s electrical grid—and turn off their engines—when berthed. (Then-minister of transport Lisa Raitt called the $10-million joint investment that funded the project a commitment “to developing this industry in an environmentally sustainable [way].”)

But there are drawbacks to shore power: Only a fraction of cruise ships arriving in Halifax make use of it—and the port can only accommodate one ship using shore power at a time. In a cruise season with 150 to 190 ship arrivals, typically “between 20 and 30” of those arrivals will plug into Halifax’s electrical grid, Port of Halifax spokesperson Emily Richardson tells The Coast. The rest? They’ll keep their engines running to power the cruise deck pools, ballrooms, kitchens and bars that lure passengers aboard—and in the process, pump thousands of tonnes of carbon dioxide into the air. (Even those plugged into shore power, it’s worth noting, are still drawing electricity from a provincial grid powered largely by coal and oil.)

The Coast asked Holland America Line, Norwegian Cruise Line, Princess Cruises, Royal Caribbean International, Celebrity Cruises and Carnival Cruise Line—which account for the majority of cruise ships arriving in Halifax—what percentage of their ships would connect to shore power in Halifax.

In an emailed reply to The Coast, a Holland America spokesperson says the company “is committed to shore power wherever local conditions allow,” but does not specify how many of its ships would make use of shore power in Halifax. In another response, a Princess Cruises spokesperson says the company’s goal “is to connect 100% of all PCL ships” docking in Halifax to shore power. Representatives from Royal Caribbean, Celebrity Cruises and Carnival Cruise Line did not respond to The Coast’s inquiries. A Norwegian Cruise Line spokesperson promised the company’s annual sustainability report “is slated to publish soon.”

If some of the answers to the industry’s emissions lie with the port itself, more rests on the cruise ship operators—and specifically, with the biggest cruise lines. One recent study found the two biggest cruise operators, Carnival Corporation and Royal Caribbean, emitted four to 10 times the amount of sulfur oxide than all of Europe’s 260 million cars in 2017. Those operators, for their part, have spoken plenty about shifting to more sustainable practices: Holland America Line (a Carnival company) tells The Coast it “aspires” to achieve net-carbon-neutral emissions by 2050, and a 20% drop from its 2019 baseline by 2030. Princess Cruises says its ships “go above and beyond” Canada’s environmental regulations, and its “state-of-the-art” air-quality systems use salt water “to ‘scrub’ 99% of sulfur from the ships’ exhaust.”

Scrubbers—exhaust gas cleaning systems that use ocean water to filter particulate matter—are the shipping industry’s latest answer to curbing air pollution, and indeed, they’re tremendously effective at lowering sulfur levels on ships’ decks and in port cities. The problem is that sulfur doesn’t magically vanish, it just gets flushed underwater. (Imagine “an exhaust tea” of heavy metals and cancer-causing chemicals, Barford says, and that’s what ship scrubbing systems produce.) Moreover, the Atlantic Ocean is naturally cold and basic. Scrubber wash water, on the other hand, tends to be warm and acidic.

“This,” Barford tells The Coast, “is sort of the exact opposite of what an ocean should be.”

The business of cruise ships

The economic case for supporting Halifax’s cruise industry is fairly straightforward. Just ask a tour operator, downtown pub or gift shop selling tartan-patterned T-shirts: The money is good. In 2022, according to the Port of Halifax, the industry brought an estimated $136 million into Halifax and surrounding communities like Lunenburg, Mahone Bay and Peggy’s Cove. That figure was an estimated $165 million in 2019, the last year of cruise operations before the COVID-19 pandemic.

For proprietors like Brian Titus, the president of Halifax Seaport-based Garrison Brewing Co., cruise ships represent thousands of new customers over the span of a season. The craft brewing company is able to “more than double” its staff every summer, he says, speaking with The Coast from the taproom on Marginal Road.

“That makes me feel good, because it’s mostly students that come on for that time period,” he adds, “and they need the money… And for me, it’s just interesting to talk to people—whether they’re from Virginia, or Florida, or Ontario or wherever. It’s always interesting to hear their story.”

For the most part, Halifax council has been vocally supportive of cruise travel—and more broadly, the tourism industry in general.

“I look forward to welcoming new and returning visitors to our beautiful port city, and our many special communities that stretch from our vibrant downtowns to coastal villages, ocean beaches and wilderness escapes,” mayor Mike Savage said in 2018. “This is an exciting time to be involved in the tourism industry.”

But for its advantages, there are limitations to the money that comes into a city from cruise travel: By and large, passengers aren’t booking hotel rooms or bed and breakfasts—nor, in some cases, are they eating out at restaurants if their breakfasts, lunches and dinners are included on the ship. Some cruise passengers opt not to leave the vessel at all when it’s in port: One survey found as many as a third of Americans polled said they prefer to stay on a cruise ship when it’s in port, instead of disembark.

As of 2018, cruise travel accounted for roughly 15% of all tourism dollars brought into Halifax. Which begs the question: If it disappeared tomorrow, how deeply would its absence be felt?

Calls for stricter environmental laws

Ask Barford, and she’ll tell you she isn’t opposed to cruise ships and the economy they support; she merely wants to see the industry adopt—and adhere to—more stringent environmental regulations. As it stands, Canada’s laws governing ship pollution are more lax than those in the United States. California does not allow ships to operate scrubbers within 24 nautical miles of its coastline. Washington state’s Puget Sound has been a no-discharge zone for ship sewage since 2018. The same is true for all of New Hampshire’s coastal waters, much of Massachusetts and most of Connecticut.

Last April, Transport Canada introduced a suite of new environmental measures intended to “strengthen Canadian discharge requirements,” including barring ships from dumping sewage and greywater within three nautical miles from shore “where geographically possible” (a law also enforced in the US), but there was one noticeable flaw, according to Barford: The measures were all voluntary. And while the transport authority promised last year’s changes would “set the foundation for a regulatory posture in 2023,” no further regulations have come.

“We haven’t had any kind of move from voluntary to mandatory [compliance],” Barford says. “So that’s really what we're looking for.”

Barford and her colleagues at Stand.earth are behind an online petition for Canada to put an end to cruise ship dumping. They’ve garnered more than 55,000 signatures on a letter delivered to federal transport minister Omar Alghabra, calling on Ottawa to “pass legal protections for the kelp forest ecosystem and endangered species” and end “the dumping of untreated and undertreated wastes from ships” in Canada’s waters.

To date, neither Alghabra nor Transport Canada have responded to the letter, Barford says.

It’s worth wondering: Could Nova Scotia intervene and roll out its own ocean pollution laws, akin to its US neighbours?

Last year, Transport Canada promised a “regulatory posture” for shipping waste would come in 2023. It hasn’t arrived yet.

tweet this

Not so, says Mike Kofahl, a staff lawyer and marine law specialist at East Coast Environmental Law. That’s because, up to 12 nautical miles from shore, shipping falls under federal jurisdiction. The Territorial Sea and Fishing Zones Act (now the Oceans Act) established those boundaries in 1970.

“In the States, there’s a little bit more control there, just based on their own constitutional structure,” Kofahl says, speaking by phone with The Coast, “which gives [those states] more flexibility and power to do their own thing.”

Where to go from here? Coast readers weigh in

Finding an answer to the cruise ship conundrum depends, in some respects, on your faith in the industry’s pledges to reduce its environmental footprint. It also depends on what you deem more important: Money in hand, or healthier air and water in the future.

Opinions were largely split along those lines in this week’s Coast reader poll. More than half of respondents said “money” is the most significant thing cruise ships bring to Halifax. One in four said “pollution” is the industry’s most lasting impact.

“Cruise ships are floating landfills, worsened by the fossil fuel consumed and sewage they dump,” writes Coast reader Kath Nolan. “Ports of entry should mandate much higher environmental standards and modifications before they are allowed to dock.”

“Hate them or love them, but they do help the economy,” Coast reader Mary Walsh counters. “Local crafters get noticed and a chance to sell products. I think for the most part, it’s local people who have no business or who make no money from [the ships] that are the naysayers.”

“All commerce pollutes,” Coast reader Chris Hartt argues. “But without commerce, there are no taxes to pay for programs. We need to minimize the pollution while maximizing the economic activity [that these ships bring].”