Getting to Africville on foot is next to impossible—there's no way to safely (or legally) get there without putting yourself in danger. The site of the former community is severed from the rest of the city by the four lanes of Barrington Street, a rail corridor and Africville Road; no sidewalks lead there, and no matter which route you choose, you're taking your life in your hands.

My plan was to make two attempts: The first, north on Novalea until the Africville trails, passing below the MacKay Bridge. The second, up Barrington—treacherous and sidewalk-less for stretches—until the fork at Africville Road.

The idea was to examine the journey, through the lens of an African Nova Scotian, exploring what emotions or memories popped up crossing an urban landscape dense with unearthed Black history.

My starting point was Mulgrave Park, where I grew up and where many residents are descendants of Africville. Living there as a child, I didn't know much about Africville—only that this community of Black residents, first settled in the 1700s on the outskirts of Halifax, was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. (Though expropriation of its land began as far back as the 1800s, with the installation of the railway.) I didn't know what life was like there, or how it might have been different from life in Mulgrave Park in the city's north end or in the communities where my own roots run deeper: On the maternal side of the family, North Preston, on my paternal side, Beechville. Both rural, and both places where I have a homestead to visit, a place I feel I belong.

I had seen pictures of Africville and the people in them looked just like members of my own communities. As a kid, I wondered if they'd talked and walked the same. Although I'm African Nova Scotian, I felt like a stranger approaching these journeys—yes, our ancestors got here the same way, but there was a great divide.

The first walk didn't last long. I started on the block in Mulgrave Park that I used to call home, surrounded by murals on both sides: one a memorial to Tyler Richards, the other about women empowerment. As I walked I was flooded with warm memories: learning to ride my bike without training wheels for the first time; chasing after Dickie Dee's ice cream trucks. I kept west on Duffus Street and turned north onto Novalea Drive. By the time I got to Novalea's northernmost point, my trip down memory lane was halted by the blaring sounds of cars on the MacKay Bridge. Immediately the area felt unwelcoming.

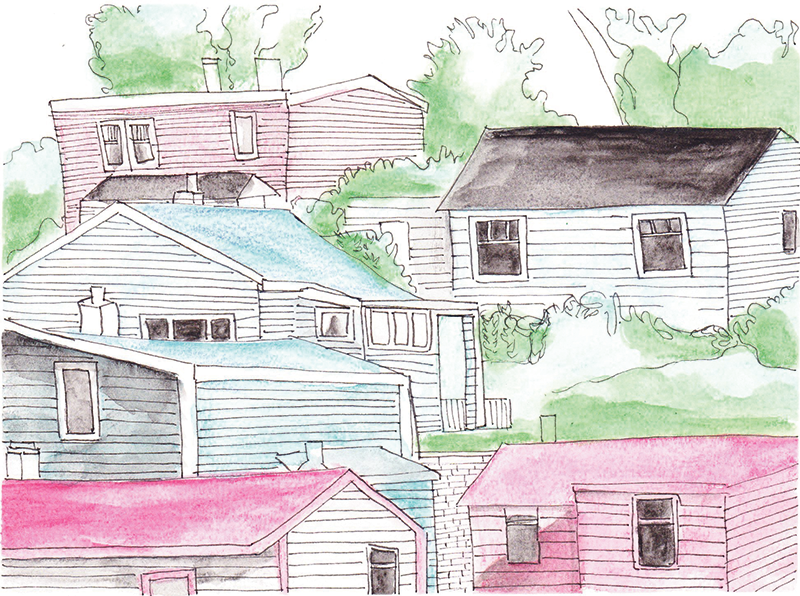

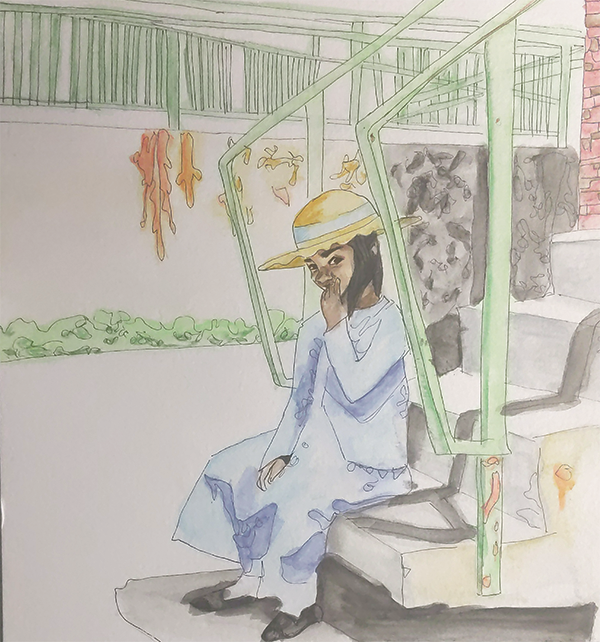

Africville, at its peak, wasn't confined to today's Africville Park—it sprawled out of the harbour, houses clinging to the steep hillside. I wasn't sure if where I stood had been a part of Africville, but I already felt its absence; wondering if I was stepping in someone's backyard, where they hung their clothes on the line, or on their front lawn, where they greeted family and friends. I could barely see the Africville Museum from across the highway and saw no safe way to proceed—it felt like I shouldn't be here, so I turned around.

As a child, whenever my mother and I would leave the city to go to my grandmother's in North Preston, I would look at her and say "I love you." She turned to me one day and said, laughing, "No you don't. You're just excited to see your cousins." Leaving the city, where I felt invisible, and going into my community, filled with Black people, was energizing. My grandparents' house on Sundays was always filled with family, more food than you could eat and my grandfather playing his guitar into the night.

One summer day, one of my uncles was building go-karts with the kids. After seeing my cousins', I wanted to make one too. My uncle built the structure, but we had to scavenge everything else, so we walked to the dump to find supplies. After putting everything together, my cousins and I rode our go-karts all day long. My summers in North Preston left me dirty, sweaty and covered in scrapes and scratches, the testament of a childhood well-lived.

I didn't spend as much time in Beechville as a child, but I remember sitting in front of my grandfather's woodstove, a pile of chopped logs nearby. He was strong, no-nonsense; tough, but soft with his grandchildren. I still try to visit Beechville often, and I treasure the moments I can sit with my great uncles and play softball with the Beechville Rockets. Getting to know my community made me feel grounded, more like I belong in this province. The city robbed the citizens of Africville of that, as became clear when I spoke with two former residents, Gary Steed and Nelson Carvery.

Steed was 11 years old when he and his family were evicted. He told me Africville was separated into three sections—he lived in the middle section. I asked what it was like when he was a boy. He said that it was tight-knit, self-sufficient, a complete community with stores and schools and much better kept-up than its reputation. When he left, everything got worse for him: racist schools, getting in and out of trouble. I was curious what made him the hardworking entrepreneur he is today. He ascribed it to growing up in a self-reliant Black community.

Nelson Carvery was 19 years old when he left Africville. He talked about playing baseball in the summer and hockey in the winter by the Bedford Basin. Like me, he played near the local dump—which was placed by the city government at Africville's western edge in the 1950s, after being rejected by other (read: whiter) communities. He used it, not just for play, but to make money selling things he found. In the same way, he and other residents turned the rail line—placed here in 1854, cutting the community in two—into an asset. They'd hop on to the freight trains that slowed as they passed through, throw off the coal from open rail cars, bag it up and use it to heat their homes.

After talking to Steed and Carvery, walking through Mulgrave Park was different. Instead of my own experiences, I thought about how Africville could have developed and grown. What would it have looked like today? Would Halifax have more Black business owners? More Black teachers? If its growth wasn't violently disrupted, would it have thrived?

My second attempt came on Heritage Day—this year dedicated to Africville—and I was determined to make it this time. I headed east along Duffus, out of Mulgrave Park, and turned north onto Barrington. There was no sidewalk on the other side, and I had to walk behind the guardrail that separated me from oncoming traffic. The ground was uneven, the terrain was rougher and I quickly became sweaty and exhausted. I was running out of walkway, so I made the climb over the guardrail on to the highway, cars zipping past me. With every car that passed, with all the pavement and gravel, I found it hard to imagine the Africville that Steed and Carvery had described to me.

I crossed the train tracks and the road (still no sidewalks) and finally made it into the park. At this point I felt disheveled. I was panting, my feet were wet and I was sticky from sweating. Still, I walked closer to my endpoint, the Museum, located in the area Carvery called Big Africville, where kids went to school and the community attended church.

Usually empty, the park today was full of people celebrating the community and its legacy—kids sledding with their parents, people of all ages and races learning about its history. When I walked inside the museum, it was a packed house, and to my surprise I found the Beechville choir, with my aunt singing and relatives in the crowd—I'd begun this journey feeling like a stranger, and here was a family reunion.

Churches, for most Black communities in the province, are the heartbeat of the community, and I recognized people here from New Horizons Baptist Church, Saint Thomas Baptist Church, as well as Emmanuel Baptist Church. And I learned something new: a small piece of Africville has been in Beechville's Baptist Church for the past 53 years: When Africville's church was demolished, the members of Beechville Baptist Church saved the bell, and in the next few months, it will finally make its return to Africville.

The strength and legacy of Africville is in its people, its stories and experiences. Though its buildings are gone, those stories—like that bell—are still with us to be passed on for generations to come.

Letitia Fraser is an artist, with a focus in painting and textile. Born and raised in Halifax, she is a proud descendant of North Preston.