Acknowledging we are on Mi’kmaw territory is planting the seed of reconciliation in Nova Scotia.

Last week the Halifax Regional School Board voted to include an acknowledgement during morning announcements that schools sit on Mi’kmaw land, and in October the

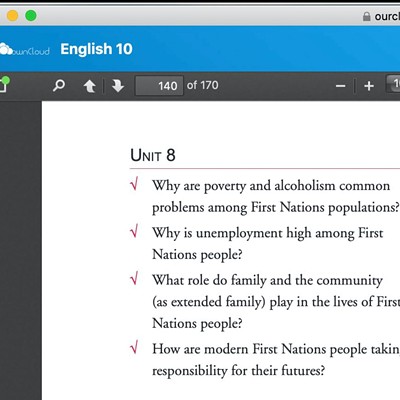

Wyatt White, the department’s director of M’ikmaq Services, says they’ve used the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s “calls to action” to fill the gap between the historical and social studies context and create a “better understanding of Mi’kmaw culture.”

Education is key to the reconciliation process. In order to analyze current Indigenous issues, we need to focus not just on Indigenous history, but how it relates to present day Indigenous affairs and the struggles faced by Canadian Indigenous peoples. As chair of the TRC Justice Murray Sinclair said, “Education got us into this mess and education will get us out.”

Went to high school in Alberta and we kind of just grazed over it. Learned more in university and even here working at the elementary.

— Rachel Lee (@sugarshenanu) June 5, 2017

Jessica Dupuy is a Mi’kmaw support worker in HRM. When she was growing up, it was challenging to learn about Indigenous culture.

“It was always talked about like it was ancient history,” she says. “We’re having these problems in modern society and we need a space to talk and educate each other. To create a dialogue so we can start fixing some of this stuff.”

Sophie Doyle, a Grade 11 student at Charles P. Allen High School, says her perspective of Indigenous peoples has changed since taking the school’s Mi’kmaq studies class. She entered with an admitted ignorance and a “stereotypical view,” but finished the class with a deeper respect for other cultures.

“Canada’s history isn’t as clean as I thought it was,” Doyle says, “I mean, Canada is always portrayed as this great amazing country—and it still is—but we do have some dark patches in our history.”

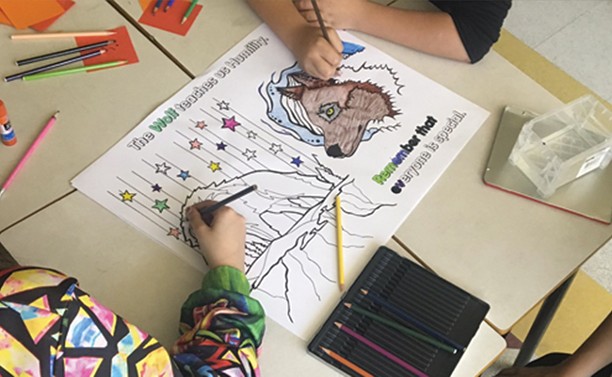

Dionne Reid teaches the class at Charles P. Allen High School, which includes units on Mi’kma’ki (the traditional grounds of the Mi’kmaq people), early and traditional life, how European presence impacted Indigenous spirituality and culture and the residential school systems. The students also create an independent study at the end of the course where they choose their own topic to explore in-depth.

Without this knowledge, says Reid, society is able to turn a blind eye to what’s happening to our Indigenous peoples.

“They only see the one side of the social problems in the communities, on the reserves and the 5,000 or so Indigenous people living off-reserve in the HRM. They see that but have no concept of the underlying reasons. Which is so sad,” she says. “It allows people to be racist, basically.”

Grew up in Tsawwassen (that has the Tsawwassen First Nation reserve just north of the town) and didn't learn a damn thing.

— Nessa Rose (@janessaarosee) June 5, 2017

Nova Scotia began offering Mi’kmaq 11 in 2003 as a Canadian Content credit. Students can choose between Canadian History, African Canadian Studies or Mi’kmaq Studies. In some parts of the country, though, learning about Indigenous history isn’t an elective.

In the Northwest Territories, Northern Studies is a mandatory course for high school students looking to graduate. Having the opportunity to learn about Canada’s dark history helps those students understand how intricately our Indigenous community has been devastated.

“I feel like from a young age we’re taught certain things from certain cultures that aren’t necessarily true,” says Doyle, who believes all students should learn about the Indigenous cultures native to the areas they live. “I think it’s really important to be aware of our history.”

For Reid, the kids in our school system are the game-changers. It’s up to us all to raise them as fully-informed adults if we ever want to instil positive change in our democracy.

“The kids that I see graduate out of this course, they are empathetic,” she says. “They are appalled. They’re angry. They can’t believe that this cultural genocide happened in our country.”

Acknowledging and learning the reality of Canada’s past is the first step