A

Those shocking details are contained in two new investigations released Wednesday by Nova Scotia’s Information and Privacy Commissioner.

According to Catherine Tully’s office, from 2015 to late 2017 a manager at one of Sobey’s rural pharmacies illegally accessed prescription histories, medical conditions and other personal health information for 46 individuals.

The pharmacist in question would casually discuss the privacy breaches in front of employees and gossip about what she discovered with her spouse.

“This is a case of a pharmacist accessing highly sensitive personal health information over a two-year period to satisfy personal curiosity,” reads the report.

Upon learning she was being investigated, the manager tried to get other employees to lie for her and even visited the homes of the people whose medical privacy she violated hoping to get them to sign off on homemade consent forms.

In the end, she was fined $9,000 and given a six-month suspension on her pharmacy license.

While there are administrative safeguards in place that are supposed to prevent events such as this, “they were not effectively used and are not sufficient to protect Nova Scotians from this type of ‘snooping’ behaviour.”

The privacy commissioner found both Sobeys and the Department of Health and Wellness failed to adequately monitor access to personal health information. Inquiries into the breach that were conducted by both the company and the province’s health department failed to properly investigate the crime and wrongly concluded there was no evidence of malicious intent.

The frightening conclusion, says Tully, is that personal health information in Nova Scotia is critically vulnerable.

“Intrusion into the private lives of patients is a real and present danger.”

Although unnamed in the OIPC investigation, the pharmacist in question appears to be Robyn Keddy, who’s still listed as the manager for the Sobeys Greenwood in Kingston.

A recent hearing decision from the Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists states that Keddy “unlawfully accessed patient files, some on multiple occasions, with no valid, clinical, medical or professional reason.” It also states that she was fired in September of last year for the privacy breach.

Those and other details in the college's decision match with the facts released by the privacy commissioner.

Concerns about the unauthorized use of medical information were first raised by the Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists last summer. Likely acting on a tip, the OIPC says the college notified Keddy back in August that it would be conducting an audit.

Witnesses say Keddy panicked after being informed about the site visit, told coworkers she was considering going on sick leave and began adding notations to the files she had illegally accessed. She also, futilely, tried to get other employees to assist her in coming up with reasons for all the unauthorized access logged in the computer.

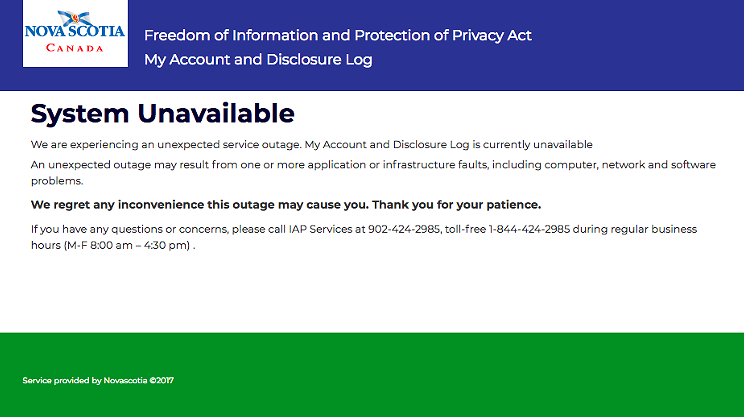

The Provincial Drug Information System is a multi-use database operated by the province and used by over 11,000 doctors, pharmacists and health practitioners. Once a user is trained on and given access to the system, they can view the confidential medical information of any person in Nova Scotia.

In order for a pharmacist to bring up that medical history, the subject would first need to be a patient at that particular pharmacy. Keddy used a workaround by created fake customer profiles for whoever she wanted to snoop on, which she was then able to use to access detailed, sensitive medical records.

The individuals include Keddy’s doctor, coworkers, former classmates and her child’s therapist, teachers and girlfriend.

One Sobeys coworker witnessed Keddy access the DIS and then call her spouse to discuss what she had discovered. She allegedly told her husband their child couldn’t see his girlfriend anymore because of the medications the young woman and her parents were prescribed.

Several of Sobeys’ employees gave evidence that they were aware of the unauthorized access “for some time.” They would either overhear Keddy talking about it on the phone to her husband or she would discuss the breach of privacy law directly with her employees. The pharmacy staff hesitated to report the violations because Keddy was their supervisor.

“They feared they would not be believed and they would suffer some form of retaliation.”

The college’s audit was eventually provided to the Department of Health and Wellness, which shared the findings with Sobeys. Keddy was fired shortly thereafter because of the privacy breaches.

After losing her job, she and her husband visited the homes of at least a dozen of the individuals whose privacy she had violated, asking them to sign a homemade and retroactively dated consent form.

Despite all the evidence and witnesses, the initial investigation from the province concluded only that Keddy had used the system to lock up cell phone numbers for people she knew.

“To be clear, even if the pharmacist had genuinely been looking up contact information, using a sensitive health information system as a personal phone book would not have been an authorized access and would have been considered a privacy breach,” writes the OIPC.

Instead of a phonebook, however, Keddy was using the medical information because she was nosy. The privacy commissioner’s office determined the pharmacist had a personal relationship with all of the impacted individuals and casually disclosed that sensitive information to her spouse.

“The temptation to ‘snoop’ is difficult for some individuals to resist,” Tully says in Wednesday’s release. “Custodians of electronic health records must anticipate and plan for the intentional abuse of access by authorized users.”

The commissioner made 10 recommendations for improving and strengthening provincial privacy controls, including adjusting departmental protocol so that if a user is found to have breached personal privacy, their actions are audited for all other implicated databases. Tully also says notification to affected parties should happen within days, not weeks or months.

As for Sobeys, the OIPC’s eight recommendations include developing a privacy breach protocol and training for managers within the next six months, immediately notifying the 28 people whose information was copied into its system (and delete what profiles still exist) and create new policies to document all database access any time when prescriptions are not being dispensed.

Tully also personally wrote to the minister of Health asking for prosecution time limits for health privacy breaches to be lengthened to a more realistic two years, instead of the six-month limit currently used.

For agreeing to the findings of professional misconduct from the college of pharmacists, Keddy was fined $5,000 (plus $4,000 in legal costs), had her pharmacy license suspended for six months and must attend a business ethics course. A letter of reprimand has also been placed on her file.