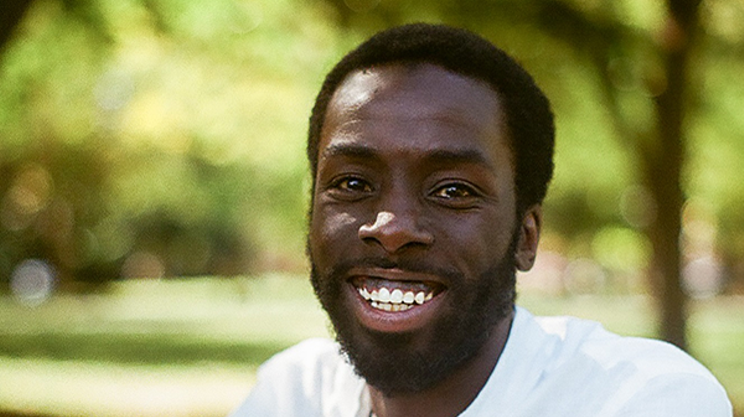

Just days after the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission delivered its landmark report on street checks last March, DeRico Symonds took to the streets.

Despite the report's finding that Black people in Halifax were six times more likely to be stopped by police than their representation in the population would suggest, and the Black community's cries for a ban—or at the very least, a moratorium—those in power were hesitating to make any big changes.

So Symonds, a young, Black community leader, donned a hood and a red banner reading 'Ban Street Checks,' and led a crowd of around 100 community members on a march through Halifax's north end.

"No justice, no peace. No racist police," came the crowd's rallying chants, as they tracked down Gottingen Street, pausing in front of police headquarters.

"It just has to be a complete ban," Symonds told the crowd gathered in the Halifax North Memorial Public Library before the march.

Now, months after the commission's report, the province's until-further-notice moratorium and generations of stories of pain and fear expressed by the African Nova Scotian community, the province has at last handed down a ban.

While members of Nova Scotia's Black community see this as a long-awaited win, the conversation about systemic racism in the province is only just ramping up.

Whose voices count?

It's become an old line in this conversation— the Black community has been decrying racial bias in Nova Scotia's policing for decades, so a decision to ban street checks should never have taken so long.

"I understand government, and I understand that there's a process that needs to be had, and individuals want to take care and do their due diligence before making a decision," says Symonds.

Still, he notes, despite decades of rallies, marches and legal challenges, it took written reports from two white men—first, University of Toronto criminology professor Scot Wortley and then former chief justice Michael MacDonald—to validate the Black community's concerns.

The empirical nature of the data, says Scot Wortley, made the findings of the report more palatable to "people who look like me," confirming the concerns the Black community had been expressing. He acknowledges that his report had little educational value for the Black community. "That's their lived experiences, that's what they've been living for centuries in Nova Scotia," he says in an interview over the phone.

Symonds agrees. "When the decision happened I thought it was great, but the events that led up to that decision were kind of weird," he says.

"I understand there's due diligence to be done, and I do believe he wanted to make the right decision, but the facts are there were two white males involved at points where the Black community was saying one thing, but then it took those two folks to validate it."

Regardless of how it came about, Symonds says the decision to ban street checks is still a win.

"It's a small win in the big pot and the upstream conversation around racism," says Symonds. "The symptom is street checks...but the actual diagnosis would be racism."

As the conversation around street checks has unfolded over the past two years, the community has been adamant that these stops represent only a small part of the tensions between police and racialized communities in Halifax.

With a ban in place, Symonds says the community is left to wonder what comes next.

"I'm looking for accountability, I'm looking for community to be involved, and I'm looking for transparency on policies and practices and work needing to happen within the structure of the department itself," says Symonds.

What took so long?

Halifax's Black community had been challenging the practice of street checks and police stops for decades, but the issue only started to garner public attention in 2017, when a CBC investigation hinted that the practice, under fire in Ontario at the time, disproportionately affected the city's Black population.

In March, the NSHRC released Wortley's report, which laid empirical data side by side with harrowing tales of lived experience, compiling the community's cries for justice in one damning document.

At the time, it was reported that the province was moving towards "strict regulation" of the practice, working with a group of youth, police, human rights commissioners and Department of Justice staff to determine the best course forward.

Symonds was part of that Wortley Street Check Action Working group, but as the province dug in on regulation—even though he and other members were adamant about a ban—he and two others walked away, causing the group to dissolve.

In the meantime, the Board of Police Commissioners enlisted Jennifer Taylor and former chief justice Michael MacDonald to conduct an independent judicial review of the legality of street checks, as Wortley had recommended in his report. The mid-October arrival of the review ultimately sealed the deal.

"We have concluded that the common law does not empower the police to conduct street checks, because they are not reasonably necessary. They are therefore illegal," MacDonald and Taylor wrote in their report.

Days later, Furey delivered the news. "The decision that I've come to, based on a number of contributing factors is we will move to take the moratorium to a permanent ban on street checks," he told reporters.

Will it be enough?

MacDonald's judicial review points out that what's at stake in the street check issue is the right to be "left alone, free from state interference," but Wortley worries that this freedom isn't actually guaranteed by a street check ban.

He says police still lack strict regulation to navigate police stops that fall under different names, like motor vehicle stops—including the 2003 Kirk Johnson incident that sparked the first inquiries into racial bias among Nova Scotia's police—and police stops tied to actual investigations.

"One of my worries about the ban on street checks is that the behaviour...the community which is being stopped, detained, questioned and sometimes searched, can still continue even if there is a ban on street checks. It just will not be reported in a police dataset anymore," says Wortley.

"Only time will see if this ban alone will be adequate, or if there's other measures that need to be taken, but it is a positive first step."

What about the data?

Without a dataset from street checks, Wortley says that going forward, data collection should be ramped up for those other types of stops.

"We need to start collecting race-based data, as well as gender and age and geography and reasons and all these types of things, for both traffic and pedestrian stops," he says.

In June, after the release of Wortley's initial report, the HRP presented a plan to the Board of Police Commissioners that would see all historical street check data purged by December 2020.

Until that point, members of the public are invited to request their own information through the HRP's freedom of information application process, but by 2021 all street check data and metadata—used for research like Wortley's report—is slated to disappear.

In Wortley's view, eliminating the data entirely could prove dangerous for the police department. "The data collection in some ways becomes a form of accountability."

The police are staying mum on the decision about the dataset until a complete recommendation can be brought to the board.

And when it comes to holding the police accountable for the racial injustice inherent in street checks, the HRP is staying predictably vague about their disciplinary plans.

Police chief Dan Kinsella was unavailable for an interview for this story, but when asked whether there will be consequences for officers who conduct street checks in the future, HRP spokesperson John MacLeod wrote in an email that, "stopping people on the basis of race, background or any other discriminatory reason is not acceptable." He says the consequences may include disciplinary action, training or as determined.

"As the chief of police has stated, this issue will have his close, personal attention along with senior members of the team, and every report will be followed up on thoroughly," he added. "As far as HRP is concerned, a ban means we no longer conduct street checks, and the associated mechanism has been disabled."

What's next?

Even with the mechanism—or symptom—now out of the picture, the real diagnosis, as Symonds puts it, still persists.

Shortly after MacDonald's report was released, Kinsella told the Board of Police Commissioners that the force would prepare an "all-encompassing" apology—something the community has been asking for persistently—for street checks and "some 200 years of inequalities and injustices" by the end of January 2020.

Even Kinsella recognizes that institutional apologies, while well-intentioned, can be hollow. Along with that apology, Kinsella told reporters he would also be working toward a "robust action plan" to address systemic racism in policing.

It's that forward-looking conversation that Symonds is ultimately hoping the street check issue will bring to life.

"I think that it's imperative that we have to have the upstream conversation and acknowledgement of, 'it's not just street checks.' There's racial bias, there's racism within the system and it's going to take more than just a single ban of street checks to combat the racism from within," he says.

With the promise of an apology, along with the hinted suggestion of continued action, Symonds remains hopeful that the community will continue to be involved in conversations around issues of racial justice in the province. But he'd like to see the whole city bring the same energy to the issue of street checks and systemic racism that they bring to the Uber, sidewalk clearing or taxi cab debates.

"People need to be made uncomfortable," says Symonds, "to then be comfortable and move forward in a positive way."