A year ago this Saturday, April 17, three residents of Northwood, the long-term care centre in the heart of Halifax, died of COVID-19. Fifty more would die in the course of the next six, frantic weeks.

While COVID raged inside the facility, the north end complex was sealed off from the surrounding community. The virus raced through its narrow, windowless hallways and up the floors to the most vulnerable residents, whose ability to understand what was happening had been stolen by dementia. Outside, people gathered to applaud the health care workers changing shifts, and they tied encouraging posters—Northwood Strong!—to the fence across the road. Inside, it was mayhem: staff got sick, or quit their jobs in fear, leaving just two or three care workers to feed and change and bathe a unit full of residents. Northwood ran out of space to separate the sick from the well, and exhausted aides struggled to try to keep infected, confused and lonely patients in their rooms. As control slipped from their grasp, a senior administrator emailed his team that they should “assume every resident is positive.”

The last COVID-infected Northwood resident died on May 30; the outbreak was declared over shortly after. The province held a closed-door review of the pandemic deaths at Northwood, but did not release its findings. A year has gone by without more COVID deaths in long-term care in Nova Scotia, without even an outbreak. That has helped to create a sense that what happened at Northwood was both tragic and unavoidable.

Was it?

The Coast conducted more than 40 interviews, and reviewed hundreds of pages of documents, to piece together the sequence of events from the day COVID arrived in the province to the day the last of the 53 Northwood residents died. Together, they tell a story of a confluence of historic choices that left the facility perilously vulnerable to this virus, and a chaotic response where leadership failure collided with a cold calculus about who would be prioritized for saving.

There’s no question that what happened at Northwood was tragic.

It’s far less clear that it was unavoidable.

Part 1

Northwood’s promise

In 1988, Halifax hosted a national conference on geriatric care. Most of the meetings, a gathering of experts on supporting the frail elderly, were held downtown. But participants also took a field trip to the north end, so they could visit the Northwood complex, and see its pub, day care, beauty salon and bustling activity centre. Janice Keefe, who runs the Nova Scotia Centre on Aging at Mount Saint Vincent University, remembers how impressed the visitors were with Northwood: rather than shut away, its residents were rooted in their community.

Northwood began as the Towers, as a not-for-profit affordable housing complex for seniors built in the 1960s; in 1970, construction started on the Manor, facing Gottingen Street, which was then an assisted living facility. The nine-story Centre, a nursing home, opened six years later and over the years Northwood has transitioned to providing a more intense level of care, for older, more medically vulnerable people, with the motivational motto “We can always do better.” With space for 485 residents between the Manor and Centre, the long-term care centre is the biggest such facility east of Montreal.

Although costs have outstripped funding for long-term care over the years, Keefe said, Northwood has remained widely admired for its standard of care. However its physical infrastructure is outdated: many rooms are double occupancy, and some hold three beds. Even “single” rooms have shared washrooms—best practices in infection control today dictate that residents should be in rooms of their own, with their own bathrooms. Northwood has long, narrow corridors, and residents gather in shared common rooms at the end of the halls to get access to daylight.

But until March of 2020, the community aspect of Northwood continued: schools brought kids in for Christmas concerts, and it was a favourite neighbourhood destination on Hallowe’en. People on fixed incomes in the north end popped into the restaurant for affordable bowls of soup. Its size meant there was always activity, and always a critical mass to support a bridge tournament, a knitting circle, a Bible study. Most of its residents are retired blue collar workers, people living on small pensions or Old Age Security.

But Janet O’Dor chose it as a home for her husband, Ronald, when his early-onset Alzheimer’s required more care than she could manage at home. A marine biologist who led ocean surveys that discovered more than 1,200 species, Ronald had a pension from Dalhousie University that meant his family could afford a private nursing home. But his wife felt the vibrancy at Northwood meant more than the luxury of the furnishings. She resigned herself to putting mousetraps by his bed, a tradeoff for the way her husband’s face lit up when she took him to the sock hops and the bingo games. “The space is dreadful,” she said, “but the community aspect—it’s the fact that the fellow who washes the floors interacts with Ron every day and Ron just beams when this person comes along.”

Debi Upshaw used to pop in and out of Northwood a couple of times a day. She lives nearby, in Mulgrave Park, and she liked to check on her mother, Evelina, 94—one among a whole community of elders in the north end’s Black community who chose Northwood as a home when they needed more care. Upshaw would assist in getting her mother ready for bed some nights, and sing with her a bit. She’d help Evelina dress up and take her down to church on Sunday mornings: The New Horizons Baptist Church had been gathering its faithful at Northwood since its own building on Cornwallis Street began renovations in 2018. Those Sunday services were a place for Evelina, who ran a hot lunch program in the neighbourhood for more than 30 years, to bask in affection and familiar faces, even if she struggled to name them.

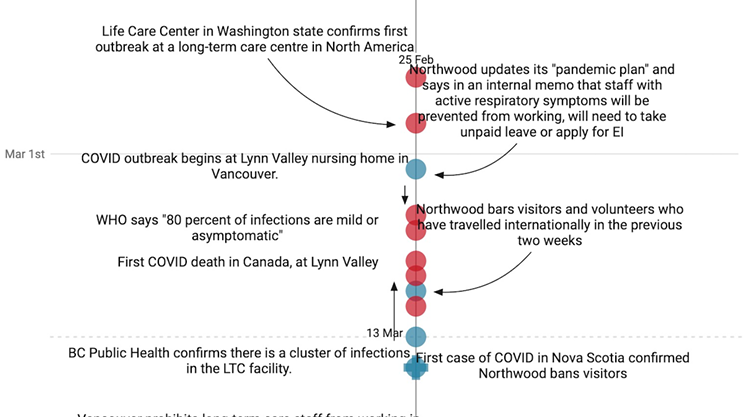

In early March last year, Upshaw began to see more and more stories about a new virus on the news, and pictures from care homes in other parts of Canada where staff were wearing masks and gloves. She wondered to herself why that wasn’t happening at Northwood, wondered if the virus might make it as far as Nova Scotia.

On March 10, Jenna Clark went to visit her father, who was 74 and had moved into Northwood a couple of months earlier, when early-onset Alzheimer’s left him unable to care for himself. He was starting to settle in, but Clark had been watching the news, too, and she feared the centre might soon bar visitors. “We took him an iPad. We said, ‘Just in case…’” If families were kept out for a week or two, Clark thought, they could Facetime.

Betsy Webb was also wondering about this new virus: her partner is from Spain, where hospitals were already treating a crush of COVID patients. Webb usually visited her 88-year-old mother, Lee Webb, at Northwood on Tuesdays, but on Sunday, March 15 she called and asked if the centre was still open. The receptionist said yes. Webb changed her clothes and hopped on her bike. But when she got to the centre, about 15 minutes later, a security guard met her at the door and told her visitors were no longer allowed in. The government of Nova Scotia announced the province’s first COVID cases Sunday; the facility was now sealed. Webb, however, insisted she could not be locked out without seeing her mother, and talked her way in. “I figured it would be at least three months. She was 88 and frail and I didn’t expect to see her alive again.”

The vanishing of the visitors was bewildering for many Northwood residents. Gerald Jackson, 84, who lived on the 8th floor of the Centre (8C as it’s known at Northwood), a dementia unit, started to phone his twin daughters, Charlene and Darlene, asking where they were. “Why aren’t you visiting me?” he demanded. “Why don’t you like me anymore? You just want me to die.” A former Navy man who liked to keep up appearances, Jackson had broken his belt; staff were using a paper clip to hold his trousers up, and he could not understand why his daughters would not bring him a replacement. “I said, ‘Dad, I’m not allowed to bring you in a belt,’” Charlene Chiddenton recalled. “He said, ‘Well, just never mind then,’ and hung up on me.”

People were watching the news inside Northwood, too. One resident of the third floor of the Centre, on Northwood Terrace, had watched the CBC’s COVID-19 town hall and was tracking the spread of the pandemic across the country. After Northwood went into lockdown, she called her daughter and said no one would tell residents what was being done to prepare the facility or protect them. “She said she couldn’t get anything, any truth, out of anyone—‘No one will tell us anything,’” her daughter, LS, said. (LS is a health care worker who was not comfortable using her full name to speak about her family’s experience because she feared repercussions for being publicly critical.) “Mom thought they were sitting ducks.”

While her mother was trying to get answers inside Northwood, frantic preparations were being made for COVID in Nova Scotia’s hospitals. Surgeries were canceled and any patient who could possibly be discharged was sent home. Intensive care staff were given updated training in infection prevention and control. Personal protective equipment was being stockpiled at the hospitals, and premier Stephen McNeil was beginning to mine contacts from his trade trips to China to try to get more. Hospitals cautiously began to offer COVID tests to individuals who had been carefully screened for risk of exposure.

Erica Surette was preoccupied, those weeks in mid-March, with how badly the pandemic would hit Nova Scotia, and what it would mean for her mother, Patricia West. Her mother was just 65, but she had early-onset dementia and had gone to stay in Northwood in late 2017. On March 20, Surette learned that Northwood planned to relocate her mother, having assessed that she needed more care than she could receive on her current floor. It meant a move out of the single room in the Manor that she had occupied since 2019 and into a shared room in the Centre. “I knew Mom needed a higher level of care, but I begged them not to move her,” Surette said. “I said, ‘You can’t be serious. Can’t we wait?’” The coronavirus was still mysterious, but a shared bedroom seemed, to Surette, like an obvious increase in risk. But Northwood administrators told her there was no telling how long the pandemic might last, so there was no point trying to wait it out. “They moved her.”

Surette drove to Northwood so a staff member could hand her the possessions that now would not fit in her mother’s new room. And, like Betsy Webb, Janet O’Dor, Debi Upshaw and hundreds of others with family members in Northwood, she waited, and braced herself for news.

Part 2

“I’ve never seen my mother afraid”

On Sunday, April 5, a Northwood long-term care staff member tested positive for COVID-19. The next day brought the first COVID death in the province, a woman who was a resident of a Cape Breton long-term care facility, the Northside Community Guest Home in North Sydney. And the day after that came the news the families had been dreading: in addition to another staff person, five Northwood residents were infected with the virus.

Staffing levels at Northwood had been minimal for years, as the province rolled back the amount it was willing to pay for care. Now a personnel crisis was developing, as members who tested positive or had been exposed to COVID went into two weeks of isolation.

Four blocks down the street from Northwood, the news of the first infections sent Linda Carvery into a spiral of uncertainty. Her 99-year-old mother, Margaret Gordon, lived in the facility, and so did her son, Derrick, 37. He had cerebral palsy, and was, Carvery said, “so fragile.” How would he resist what seemed to be unfolding at Northwood? An argument began in Carvery’s head: “I said, ‘Gosh, why don’t we just go [and get him]?…Why don’t we just bring Derrick home?’” Then another voice in her head would respond: “Linda, what are you going to do with him? The bathroom is upstairs. You can’t lug him upstairs. He’s as tall as you are.” Carvery went back and forth like this, racked with indecision about the best thing to do for her son.

On Friday, April 10—just one week before Northwood’s first COVID deaths—Erica Surette called her mother, and was startled: her voice was barely recognizable. “She said, ‘Erica, I’m sick, I’m not good.’” Surette called the nursing station, and learned that her mother had been tested for COVID shortly after she was moved into the new room. But she was negative. Maybe this was just a cold? Surette asked for another test, which she was told would be done the next day.

Saturday, April 11, Charlene Chiddenton learned her father had COVID. When she got the news, she went to Northwood wearing a bright red coat and carrying a red balloon, hoping to make her encouragement as visible to her dad as possible. She stood on the sidewalk and called the nursing station to ask that someone help Jackson to the window. There she waved to him, and an aide put him on his cellphone so they could chat for a couple of minutes. He was breathless, she said, and couldn’t talk long. When he left the window, Chiddenton collapsed sobbing on the sidewalk. A concerned passerby stopped and, from six feet away, asked if she could help, somehow.

By Sunday, no one had called Surette to tell her the results of her mother’s second COVID test; when Surette reached the nursing station, they told her “no news is good news.”

Families were struggling to understand what was happening in the complex. When the shutdown came, Debi Upshaw said, she gave the staff caring for her mother clear instructions. “I told them, ‘Keep my mom quarantined. She has her own private room, TV, everything. Just keep her in her room so she has less chance of catching it.’ Well, I call the next day and where’s my mother? Sitting out by the desk with all the rest of the seniors. I said, ‘I told you to separate my mother.’ They said, ‘Well, we figured she’d want to be out here.’ I don’t care! She has dementia! She doesn’t know.”

Renee Field was making daily calls to her mother, Diane Pace, a 77-year-old whose card shark skills had not been diminished by dementia, on the seventh floor. That weekend, Field heard on the phone that Diane had laboured breathing and was groggy; Field feared it might be COVID. A nurse told her she was likely right, but there was no way to know for sure: testing was being done by floor, and their turn was not for a day or two. By mid-week, Field got confirmation of her hunch: Diane was positive.

Cecilia Gray lives a few blocks from Northwood—she could see the complex if she took a few steps from her front door—but now she found herself battling to figure out what was happening with her 97-year-old mother. Every time she got through to the nursing station, she said, they told her it was fine—until one day in mid-April an aide answered and said that many on the floor were sick. “She said, ‘Didn’t anybody tell you that the COVID was up on the floor?’ I said, ‘No. No one called to tell me that. I didn’t know that.’ She told me that the whole floor had the COVID except for my mom and [two others]...I was devastated.”

On Monday, April 13, Erica Surette called Northwood again and had a conversation much like Gray’s: a staffer asked, “Didn’t anyone tell you? Your mother is positive.” The nurse said she would be moved to a new COVID isolation area set up on the 11th floor.

The same day, however, Northwood called Surette back and said the COVID isolation unit was full. Her mother would be staying in her room. (Her roommate had been moved out at some point in the previous few days; Surette was not told why).

LS said she was beginning to fear that staff levels on her mother’s unit had fallen insupportably low. She’d call the unit and the phone would ring endlessly; when someone answered, it was never a staff member that she knew. Finally she got her mother on the phone, and learned she was ill. LS heard fear in her voice. “That freaked me out because I've never heard my mother afraid…she said, ‘Do you think I have it?’” Her mother was tested: she had COVID. “And then she was stoic—for us, she was stoic.”

Linda Carvery’s mother, Margaret Gordon, had also tested positive. So had Debi Upshaw’s mother Evelina. Jenna Clark learned that her father’s roommate had COVID. She waited, for a week, for news he had been moved out of the double room—but he wasn’t, and no one at Northwood would answer her questions, she said. Then she saw Nova Scotia’s chief medical officer of health, Robert Strang, in one of his daily pandemic briefings with premier McNeil, reassure the province that the situation at Northwood was under control. “I do know that all the necessary steps that we can take to minimize the spread and have an outbreak under control are taking place at Northwood,” Strang said on April 13. Clark stared at the livestream in disbelief. “They were saying, ‘If someone has COVID, they’re secluded from those that don’t.’ And I was like, ‘That’s simply not true.’”

Northwood’s managers were scrambling to figure out how they could separate residents who were confirmed to have COVID from those that didn’t. They had realized the outbreak had exceeded their capacity to respond without outside help, and they appealed to Strang’s office, and the Nova Scotia Health Authority.

On the evening of April 16, Madonna MacDonald, vice-president of health services at the NSHA, emailed the authority’s emergency operations centre, and copied other senior executives. “Just off phone with Vicki Elliott-Lopez”—senior executive director of continuing care at the provincial health department—“who with Rob Strang has been given a task of Northwood containment planning,” she wrote. “They want to create a division of residents and are asking if we have space anywhere i.e. camp hill vets”—the QEII health centre’s Camp Hill Veterans Memorial Building—“to cohort residents who have turned negative post-illness.” The email was part of 840 pages of correspondence about the Northwood outbreak obtained in a freedom of information request by the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union.

Northwood was also scrambling to replace staff members who were off work, either because they were self-isolating or because they had left their jobs. That same day, Northwood CEO Janet Simm told reporters they were operating with “about 60 percent” of the staff on each unit on average—but they were rapidly hiring laid-off airport, food service and daycare workers to fill the gaps, she said.

Glory Mamngong is a personal support worker (PSW) who had been picking up shifts among the three Northwood-managed facilities, in the north end, Bedford and Chester, since she moved to Halifax in 2019. She earns $17 an hour. When the COVID outbreak began, Northwood advised staff to stick to one facility—although this was not a law, as other provinces mandated—and Mamngong worked at Shoreham Village in Chester. Now, however, Northwood told her she would be redeployed to help fill the gaps at the Halifax facility.

Mamngong was fearful, aware she would be going into the centre of the epidemic. As an asylum seeker in Canada, she is not covered under Nova Scotia’s medical system and has no MSI card; if she were to be infected, she was unsure how she would get help. But when she arrived on Gottingen Street, she volunteered for a “dirty” unit, as the medical staff were calling it, a unit full of COVID infections: “I could see that these people needed help…I think anybody who has a sense of love for humanity, if you were there you would give yourself in, because they are dependent on us.”

But that first day, as she approached the entrance to 11 Manor, her courage briefly failed: the door to the unit was plastered with huge red signs saying “Stop!” and “Caution!” she recalled. “My heart was like, ‘Oh, god, help me here.’ But I was asking myself: Why should I be afraid? What about these people?”

On April 17, Wendy McVeigh, the NSHA’s director of continuing care in the Central zone, messaged executive colleagues that of 160 staff who would normally be at Northwood, 90 were off work, self-isolating. Northwood “requires urgently” 15 registered nurses to work 12-hour day and night shifts, she wrote—these specialized staff couldn’t be replaced by laid-off waiters. “All efforts to date have not addressed gaps,” she wrote. “This effort included redeployment by VON, RC, NW Home Care employees; NSHA and retirees.” Most floors at Northwood now contained COVID-positive residents.

While that conversation was happening, Patricia West’s condition was deteriorating. On April 17, Northwood told Erica Surette they were transferring her mother to the QEII. There, she was placed in intensive care and connected to a ventilator.

Back at Northwood, Tony Ince, the provincial minister for African Nova Scotian affairs, went into the facility and was given a set of full PPE. He went to the bedside of his mother Thelma Coward-Ince, who was dying of COVID. Ince held his cellphone against her ear so his sister could say goodbye. Coward-Ince joined the Canadian naval reserve as a 16-year-old from Whitney Pier, and rose to become the first Black manager of the ship repair unit. She was one of the three Northwood residents to die of COVID on April 17, although the test results that confirmed her infection would not come back for days.

Part 3

Disaster and despair

Premier McNeil confirmed that Northwood residents had begun to die of COVID in a statement on April 18. "My greatest fear was that this virus would make its way into our long-term care homes,” he said. But he had encouraging words for families: “We are working with Northwood to implement an emergency plan to isolate the virus and protect your loved ones.”

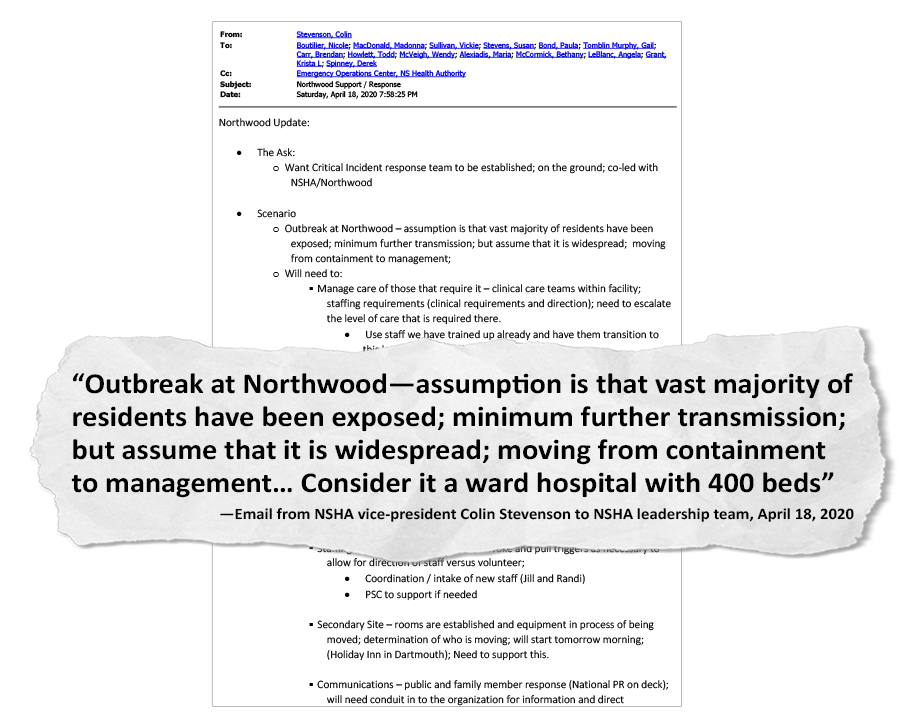

The correspondence flying between senior health officials tells a less reassuring story. On Saturday, April 18, Colin Stevenson, the NSHA’s vice-president for health systems and planning, emailed the health authority leadership team about Northwood: “assumption is that [the] vast majority of residents have been exposed…need to escalate the level of care that is required there.” The health authority would need to take the staff from Halifax hospitals who had been specially trained to manage COVID and move them to Northwood, he wrote. “Consider it a ward hospital with 400 beds.”

And he told the other executives that Northwood had hired the high-powered, Ottawa-based public relations firm National to handle messaging to the families and the public. But whatever it was telling families, Northwood still did not know the full extent of the problem it had. “Not all residents of NW have been swabbed,” Wendy McVeigh emailed Stevenson and other executives at 8:22 pm that evening, referring to nostril swabs for COVID testing. “There remains some floors with no swabbing as no symptoms exist.” There were a known 111 infected residents by now, and 40 staff. This was three weeks after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US warned that COVID could be asymptomatic in as many as half of infected people. But only Northwood units where a resident had already tested positive, or where staff confirmed to be infected had worked, were testing every resident.

Five residents were dead by the end of the weekend.

The NSHA executive was talking to the unions whose members provided care at Northwood, and they in turn had put call-outs across the province asking for volunteers—saying those who came from outside the city would have their transport and accommodation covered while they worked at Northwood. But before that appeal could produce results, the province launched its emergency plan, and health minister Randy Delorey issued a directive ordering nurses from the COVID unit at the Halifax Infirmary to move to Northwood. The implication about an unfolding horror at the care home, however, was lost on many Nova Scotians, because the parallel tragedy of the mass shooting in Portapique was also unfolding that weekend.

The next morning, an Infirmary nurse who had been redeployed headed for Northwood. (The Coast agreed to grant her anonymity because she, like a number of Northwood employees interviewed, feared retribution from her employer for speaking to the media.) She felt considerable apprehension walking towards the double doors, she said, but also a sense that drastic times called for people with skills to step up, and she was keen to do what she could to help.

When she reached the makeshift COVID ward, however, her apprehension changed to fear. There was “massive disorganization,” limited PPE, and no clarity on who would be supplying it—Northwood or the Infirmary. The protective equipment that was available was stacked in boxes in the hallway, and there was no place set up to take it on and off without risking contamination—the narrow corridors of the nursing home were nothing like the hospital stock rooms she was used to. From their first moment on the ward, she and her colleagues used the standard protocol of changing PPE every time they left a room with an infected patient, she said, but they were shocked to discover that, weeks into the outbreak, Northwood’s staff members had very different practices.

“Northwood staff would come in and put a gown on in the morning, and they would go see all the patients in the same gown and then they would wear that gown to a break room,” she said. “Through no fault of their own—they just hadn’t been educated.” The Infirmary crew was eager to implement their standards, but they faced resistance from some longtime Northwood staff. “Some viewed it as a hostile takeover…And it was like, how are we going to keep anyone here well?”

After each of the first three shifts the Infirmary nurses did at Northwood, the NSGEU email trove shows, representatives from their union called and emailed NSHA executives to report problems. Infection control was disastrous, they said, and they did not feel it was being taken seriously by Northwood managers. On April 22 the union put out a press release in which NSGEU president Jason MacLean said, “Our members are telling us it was like walking into a war zone.” At that day’s COVID briefing, Strang dismissed the release as “fear-mongering and hyperbole.”

The nurse remembers that moment vividly: Strang should see the floor where she was working, she thought. “We would have patients who are positive and with dementia and other kinds of cognitive issues, they would be going from their room and you might find them laying in another resident’s bed or visiting with another resident who was negative.” They knew they were working in the epicentre of the pandemic, but it felt surreal. “We were like, ‘Is that [infected resident] watching TV in his negative neighbour’s room?’ It was almost like, ‘Are we being punked? Is this actually happening?’”

Residents were still being fed and helped to the toilet, she said; they were getting clean clothes each day, although they had to be dressed in johnny shirts, quick to whip on and off, rather than their own clothing. But a clear clash of cultures had emerged between the Infirmary nurses, who were highly trained in infection control, and Northwood staff trained in the best practices of geriatrics, who were striving as much as possible to retain a sense of normalcy for those in their care.

Residents were still being brought together to be served meals, and to socialize; infected residents would come out to the nursing station to use the telephone. The nurses wanted it stopped. “When we said, very basic, ‘We can no longer have positive and negative people intermingling over meals in a dining room’, the response was always, ‘This is their home’…To them, not taking him out of his room, depriving him of his meal time with his friends, was unacceptable. For us, potentially making 20 other residents unwell—that was unacceptable.”

The infection control situation improved for a few days, the nurse said, but the problems would return when staff who had been off sick or quarantining came back to work. Armbands were another point of friction. The new staff wanted to put armbands on residents that would immediately identify them, at a glance, as COVID-positive or not; and contain their names and crucial information (such as choking risks), because they did not know the residents and did not have access to the charting and medical record system they were used to at the hospital. Northwood staff countered that the facility was a home, and armbands were for hospitals, the nurse said. This debate, about how much they could alter normal life inside Northwood, stood in sharp contrast to the province-wide lockdown happening outside the facility, where every aspect of life had been disrupted, streets were empty and even parks and playgrounds were closed.

On April 18, Betsy Webb was told her mother had COVID—but was asymptomatic. On April 19, Erica Surette was called to the QEII to say goodbye to her mother. She and her husband were suited up in full PPE but not allowed to enter the room where Patricia West was on a ventilator; through the glass, they watched as she was disconnected. “I still wonder what was going through her mind,” Surette said. “Was she wondering where I was? ‘Where’s Erica?’”

Darlene Metzler and her twin sister Charlene Chiddenton were, by now, extremely anxious for their father Gerald Jackson, who lived in a triple room. Northwood was providing no updates to them personally, Metzler said, only a mounting case count on its website. One hundred and eleven residents were infected. She and her sister tag-teamed phoning the nursing station; on April 20, Metzler reached a nurse.

“I said, ‘I want to know if one of the people [in the case count] is my dad, does my dad have COVID?’ ‘No.’ ‘Does one of the people in his room have COVID?’ ‘Well, we can’t say because that’s a breach of confidentiality.’ And I really pressed the issue. Having worked in health care myself for 31 years, I said, ‘No, you’re actually not breaching the confidentiality of those other two clients by telling me that one has COVID. Because I don’t know who that one would be, if there’s one person who’s diagnosed with COVID. And I want to know if there’s somebody in my father’s room that has COVID.’ And so finally, the charge nurse said to me, ‘Yes, there is somebody in the room who has tested positive.’ And I said, ‘Is that person still there?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ And I said, ‘Well, are you going to isolate the person?’ And he said, ‘No, we can't, because the COVID unit on the floor is full.’ And that’s the day I said to the charge nurse, ‘I know now what my father’s demise is: He is going to get COVID and he is going to die.’ And he said, ‘Well, we certainly will do our best for those things not to happen.’”

To Metzler, that idea was absurd. All three men in her father’s room had dementia, they were in close quarters, sharing a bathroom, and it wasn’t uncommon for them to use each other’s toothbrushes, she said. Metzler insisted she wanted her father tested. The nurse told her he had no symptoms so there was no need for the test, she said. She pushed again the next day, and the next, and finally he was tested. He was infected.

Jenna Clark, meanwhile, had escalated her campaign to try to get her father moved out of the room he was sharing with a man who was confirmed to have COVID. She had called her MLA, and officials at the health authority. Finally, in desperation, she tried social media, where a post in which she tagged Halifax Noise received significant attention. Hours later, she said, got a call from Linda Verlinden, Northwood’s client relations coordinator. And the next day her father was moved—he was taken from the room he had been sharing for at least a week with someone known to have COVID, and moved to a different double room with someone who had also just tested negative. The next day, in a turn of events that did not surprise Clark at all, her father tested positive. She does not know what happened to his new roommate.

Melinda Daye was having a similar fight: Northwood told her in mid-April that her mother, Laura, had tested negative. “I said, ‘Wonderful.’ And then I said, ‘Are there other people on the floor who are positive?’ They said yes. I said, ‘Well, you need to get Mom someplace where she’s away from the positives.’ They said, ‘Well, we’ll see. We’ll try but we can’t promise anything because of the logistics of what is happening.”

Daye, the daughter of the famed boxer and community activist Buddy Daye, launched into activist mode herself. “I was making a lot of calls and emails and whatnot because my mother was negative, but she was still on a floor with the positives. And that went on for two weeks.”

On the seventh floor, Renee Field’s mother, Diane Pace, was recovering and Field was getting regular updates from the charge nurse. In one of those calls, the woman mentioned that a close friend of Pace’s had died in the outbreak, but she didn’t know how to share the news with her. “And I said, ‘That’s not your job, I’ll tell her,’” Field recalled. “And she broke down on the phone. Hysterical crying. And my heart just—I said, ‘You need some counselling. This is too much.’ And she said, ‘We’re supposed to go to work every day and just brush this off.’”

Erica Surette’s mother, Patricia West, died alone in hospital on April 22.

The infusion of nurses from the Infirmary had helped with the high-intensity care on the COVID ward, but Northwood was still desperate for other staff to look after residents’ day-to-day needs. On April 24, Jill Flinn, the NSHA director who was overseeing the emergency recruitment, assured colleagues in an email, “They have cut out everything but the bare minimum required to ensure we know who we have brought in, that they have a license and are not on our ‘do not rehire’ list.” On April 26 other NSHA executives discussed creating a metric to determine when staffing is too low “and other measures like military have to be taken.”

The drastic personnel shortfall had produced a precipitous decline in training levels. Matthew Nette is an actor who was living on CERB and going stir crazy in the lockdown when he heard a news report about the staffing shortages at Northwood. He called up the centre to ask if he could volunteer. He said he was told public health restrictions meant no volunteers could enter the facility—but was he interested in a job? When he showed up for work, at the start of the third week of May, Nette was first deployed to tasks such as delivering meal trays and changing beds. Then managers asked if he would take the training to be a continuing care assistant. In normal times, this is a year-long course offered by community colleges. Nette said he was given a single day of classroom training—which was cut short by an hour—and then spent two days following a CCA around for on-the-job training. “And then I was allowed to give full care.”

That meant using mechanical lifts to transfer fully immobile patients in and out of beds, lifting them on and off of toilets, changing those who used diapers and cleaning catheter sites. “It made me pretty uncomfortable: I really wanted to help but I was really scared I was going to drop someone.”

There was PPE available, and hand sanitizer dispensers everywhere; he didn’t feel afraid of COVID, but he was shattered by the work. The CCA who trained him told him there would normally be five of them on the floor. Instead it was her, Nette and another young man who was also brand-new to the job. Questioned by a supervisor half way through a shift one day, Nette confessed he had not yet made it to one resident to change her, while another never got bathed. Many residents were hostile and recalcitrant, he said, and he didn’t blame them: by now, they weren’t allowed out of their rooms and those with cognitive impairments couldn’t understand why. At the end of his second week, he quit. “I was overwhelmed.”

Part 4

53 people to mourn

By April 28, 208 Northwood residents had tested positive. Gerald Jackson died that day. His daughters were offered the chance to go in to say goodbye, but felt they could not risk it: Chiddenton was acting as a caregiver for her husband’s elderly parents, while Metzler was awaiting surgery for colon cancer. “I could not take a risk of going into an infected facility that I knew was not following proper infection control protocols,” she said.

One of the few glimpses the public had at the time of what was happening inside Northwood came in a document obtained and released by the NSGEU. It was an email that Susan Stevens, the NSHA’s senior director for continuing care, wrote to her boss, systems vice-president Colin Stevenson, and to operations chief Vickie Sullivan. Stevens wrote that a member of her team, deployed to Northwood to provide resident care, was reporting challenges: PPE supplies were adequate, Stevens wrote, but access to sinks was still a problem. And staffing was still a crisis, because the residents were so ill and needed more care. The staffer reported “residents wandering about and sharing a room with residents who are [positive]. Some negative residents also wander about. Understandably, she worries about spread of the virus...Reportedly three CCAs on in morning from 7-8:30 to get all [30] residents cleaned up and ready for breakfast for 8:30 breakfast time. Reporting residents ‘likely haven’t had a bath in a week as their hair is all greasy’. ‘They are often wet but do get changed’. Most residents [are] in bed and unable to help themselves… Reportedly garbage cans are overflowing and at one point yesterday, there were no bed pans or fitted sheets available on the unit…a resident passed…and never did make [it] to an isolation room to see his one family member before passing.”

This is the kind of scenario LS was picturing for her mother, who had made it through her first week of COVID with just mild symptoms. Her children began to believe she might pull through. Then a weekend went by when they received no calls from Northwood, and when they called the nursing unit, the phone rang endlessly. Finally, her daughter spoke to another new staff person, who confided she had just begun a shift, her first ever in the facility, and that all the regular staff members, except one, were off sick.

“This young kid walked into [my mother’s] room, and I thank god she picked up the phone,” LS said. Her mother wasn’t speaking, so the aide assumed—because she didn’t know the resident and had no one around to brief her—that she was one of Northwood’s non-communicative residents. But this usually animated woman, who had previously complained to her daughter that the residents were “sitting ducks” for the virus, was actually extremely ill; it was only because LS was on the phone and could clarify that they realized something was gravely wrong.

Meanwhile Janet O’Dor got the call that her husband Ronald, the marine biologist, had tested positive. She wasn’t too alarmed: other than Alzheimer’s, which had taken his ability to speak, he was healthy, and she thought he might well pull through.

But down on 3C, Derrick Carvery was deteriorating, and his parents were called to the facility to say goodbye. Linda found it agonizing to see her son’s laboured breathing, and could not stay, but her husband Nelson lay beside their son, cued up Michael Jackson on his phone and played beloved songs through Derrick’s last hours. He died May 3, the youngest COVID victim in Nova Scotia.

His mother, at home, turned it over and over in her mind. “I would say to myself, I wonder who had the virus first, Derrick or his roommate? And if the older gentleman had the virus first, why would they not take him out of the room?...These were all conversations I was having with myself because I was so distraught.”

By now Northwood had set up a satellite unit in the Holiday Inn in Dartmouth, and residents who fully recovered from COVID were moved there. (While many, including Carvery, wondered why residents who were negative were not moved to get them out of the path of the virus, Strang explained that the fear was that a resident who tested negative initially would nevertheless turn out to be infected, producing a second outbreak centre at the hotel, and diluting the resources available to respond.) Betsy Webb had been told by staff that her mother had recovered and would be moved to the hotel. But on May 2, Webb did a video call in which her mother was breathless, speechless and could give her only a tiny smile. “It was clear she was dying.” A nurse told Webb her mother had bacterial pneumonia and would be started on antibiotics. Two days later, the same nurse told Webb her mother still had not been started on the drugs because of the staffing crisis.

That day, May 5, LS and her siblings were told they could pay a final visit to their mother. To LS, it felt like nothing had been done to try to save her, and that the neglect that resulted from the staffing crisis had aggravated her illness. “My mother had a do-not-resuscitate order. But that didn’t mean, ‘Don’t save me from COVID.’”

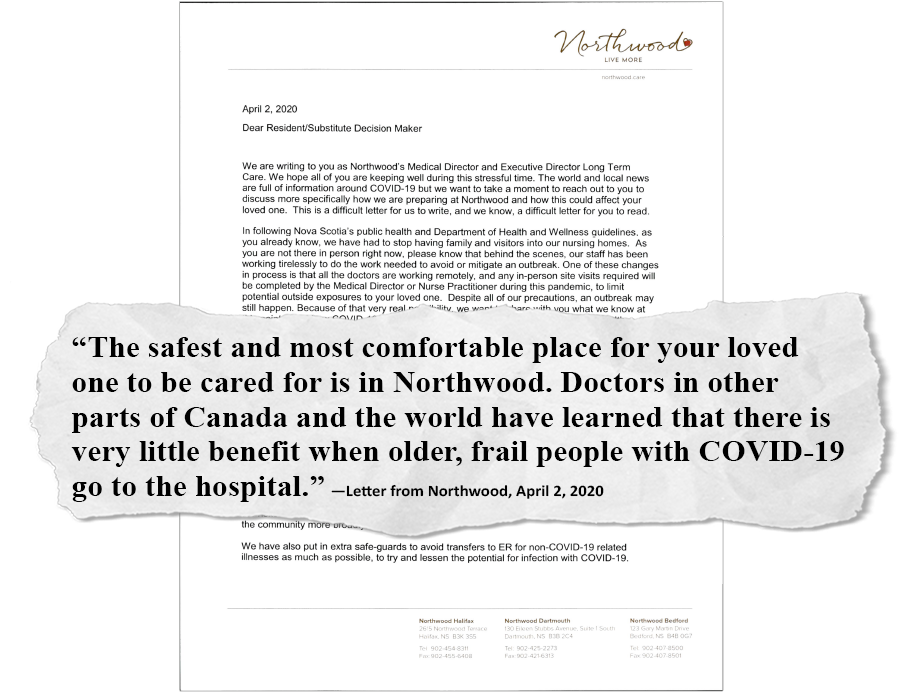

LS wondered why her mother was not being transferred to hospital. On April 2, Northwood had emailed families that the facility was “prepared to care for any of our residents who become sick with COVID-19 in our care home in special units equipped to manage this illness.” But not all residents were moved to these units—apparently because they quickly reached capacity—and in the same letter, Northwood had warned, “Doctors in other parts of Canada and the world have learned there is very little benefit when older, frail people with COVID-19 go to the hospital.” Many Northwood residents live with multiple serious, chronic conditions, and many have living wills or advanced care directives which would preclude the use of interventions such as ventilators.

Melinda Daye was still battling to get her mother Laura moved off a floor full of positive people. Finally she was taken from the sixth floor down to the first. She continued to test negative. Betsy Webb was summoned to the centre for a final visit with her mother, who was receiving palliative care. Debi Upshaw, meanwhile, was worried about Evelina’s deteriorating condition. When she learned a hospital floor had been set up with COVID, she asked why her mother had not been moved there—why she was still on a floor where, reportedly, some of the residents were either not infected or not symptomatic. “I said, Why is my mother with the well people? Why is she not being taken care of with the sick? And they said, ‘Well, there’s no sense any more [in moving patients] because almost everyone has it.’”

Then Upshaw, too, got the call to make a last visit. She suited up in PPE and climbed into the bed beside her mother. “I was singing a church song to her, and I sang the last verse and I didn’t hear her breathe any more, and I said, ‘I guess you don’t like my singing this morning, Mummy’ and there was no answer. I went around the bed and I said, ‘Thank you, Jesus, you took her home.’ She was gone.” It was May 8.

Ron O’Dor had stopped eating, and begun to deteriorate. He was moved to palliative care, and Northwood told his wife she could put on all the protective gear and visit him. “I was terrified—I’m 75,” Janet O’Dor said. “But I was preparing myself to do it. And then our two boys called, and said no, they’re not ready for their mother to die at the same time.” Over the weekend, a palliative care nurse called O’Dor periodically with updates, to say that Ron would respond briefly when she touched his cheek. Northwood asked O’Dor again, the night before Ron died, if she wanted to come in. “At that time he wasn’t even aware that anyone was there, and so I declined.” Telling this story, O’Dor stopped, and took a heavy breath. “I mean, I still feel guilt about this.” Ron died May 11.

COVID, of course, is unpredictable, and to everyone’s astonishment Lee Webb, whose daughter had been summoned to Northwood for a final visit, had begun to rally. “But she said it was all her fault,” Besty Webb said. The fear and despair outside her small room on the 5C had fused, in Lee’s dementia-haunted mind, into the idea that she was responsible for the death all around her. “She had gotten sick and made everybody else sick.”

Fourteen days after her father died, Charlene Chiddenton went to Northwood to pick up his belongings. She found herself in a line of cars in the garage, full of families doing the same thing: popping open their trunks to have televisions and bags of clothes and family photos hastily hefted inside.

The last of the 53 Northwood residents died of COVID on May 30.

Part 5

A foreseeable crisis

The seeds of the disaster at Northwood were planted years earlier. Its administrators were well aware that the double- and triple-bunking left residents vulnerable to infectious disease; a scabies infestation that had spread quickly between floors a couple of years earlier was a vivid illustration, and the facility girded for influenza season each autumn. In 2016, Northwood commissioned engineering studies that showed the building could be expanded upwards, allowing for new rooms that would permit single occupancy. In 2017, 2018 and 2019 Northwood asked the provincial government for $12.5 million to do the build. The request was rejected each year.

After the COVID outbreak, CEO Janet Simm told the Canadian Press that most of the 53 residents who died, and the 240 who were infected, were in shared rooms. “We would swab the roommate immediately, and they may have tested positive immediately, but the majority—even if they didn’t test positive immediately—within three or four days, they tested positive,” she said.

In 2015-16 the McNeil government began a series of cuts to long-term care budgets. Northwood lost $360,000 in the first year and $600,000 the next. (The 2017-18 and 2019-20 budgets restored some spending, but only back up to about 60 percent of what had been taken out of the sector). Collective agreements with publicly employed staff were frozen, including those with the already-low-paid personal care staff, and those positions became even more difficult to fill.

Staffing at a huge institution like Northwood runs much like the just-in-time delivery system at a car factory: the institution keeps as many people as possible on casual status, to avoid paying benefits. Those workers, in turn, work multiple jobs in multiple institutions, to try to make rent. “There’s no slack in the system: it’s always a tightrope of resource management,” said Chris Parsons, director of the Nova Scotia Health Coalition, an advocacy organization for public health care. “We only ever have enough resources in the system to do barely what needs to be done. So when we get hit with a pandemic, there is no slack.” With 99 staff members infected and 14 days of isolation each, Northwood lost 1,386 days of work.

Northwood is a private, not-for-profit organization, running on public money, which creates a complex decision-making structure. The facility set some of its own rules, and supplied some of its own PPE, but Strang’s office was also making rules for how to manage long-term care. The provincial government appeared to be managing the larger pandemic response well, Parsons said, so “I think that that led to people not really going after them for the fact that other jurisdictions had already started taking steps to prevent the spread in long-term care.”

Northwood runs two other care homes, which did not have outbreaks. The north end facility had unique points of vulnerability, including its size and the fact that many employees relied on public transit. “Those of us who research the sector basically would say, ‘Well, if it had to happen, thank god it was Northwood,’ because they have a good reputation for quality of care and for dedication to the staff,” said Janice Keefe, the long-term care expert at MSVU’s Centre on Aging. “So the horrible things that happened in Ontario, where residents were dehydrated, they were left—as far as I understand, that did not happen at Northwood. Yes, too many people died. But they were still being provided with care and I think that’s a story that needs to be understood. This could have been so much worse.” It’s important to remember, Keefe said, that the national guidance on masking was changing day by day, and that so much about COVID transmission was still mysterious.

Strang ordered workers in long-term care to start wearing masks on April 13, eight days after the first infected staff at Northwood were reported. “We responded within days of the national recommendations around the masking changing,” Strang told The Coast. “It took us a few days...simply because we wanted to make sure that we had appropriate supplies of masks and other PPE before we made that requirement for long-term care. There’s no point to having a policy around wearing masks if you don’t actually have any.”

Northwood CEO Janet Simm declined to speak with The Coast, and would not allow Josie Ryan, the director of long-term care at the facility, to do so either. Simm said by email that “We as a Healthcare organization have learned a lot from the COVID-19 outbreak at our Halifax Campus...It is now time for healing.” Northwood management also declined to answer emailed questions from The Coast about specifics of its pandemic response.

Some staff and family members still wonder how Nova Scotia managed to squander a protective advantage of weeks.

For Betsy Webb, it’s hard to fathom how Strang—whom she feels had handled other aspects of the pandemic well—made such a series of poor decisions about Northwood, where patients were most vulnerable. Even as a lay person, it was clear to her that his decisions did not reflect “the precautionary principle.” She knew the care workers who bathed and dressed her mother also worked multiple shifts in other facilities; she knew Northwood represented a uniquely vulnerable population.

“At least seven days before [masks] were required, we watched Dr. Strang and he said, ‘there is some evidence of asymptomatic spread, but the science is still out. We’re going to wait for the science.’ And I was sitting on my couch saying, ‘No! No, no, no, no, no. No, don’t wait for the science. Do it now,’” she recalls. “That one decision of his to wait for more evidence was huge.”

The Infirmary nurse who was deployed to Northwood also looks back and wonders at the timing. “Our only opportunity was to take the experiences of other places, and to immediately implement strategies to protect vulnerable people. We knew who was vulnerable.” Much about COVID was mysterious, she said, and she recalls the chaos of the early days of the pandemic. “But couldn’t we all see what was coming? If one or two people in an acute care facility or long-term care facility get sick, that can be catastrophic. It’s unstoppable...It is so critical at the outset to really overreact. And when you don’t do that, you lose your opportunity.”

Samir Sinha, the director of health policy research at the National Institute on Ageing and director of geriatrics at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, was tracking the steps taken to protect long-term care, province by province, a year ago, and watching Nova Scotia do least, and move slowest. The blueprint to protect facilities was laid out in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 27, he said: national guidelines on masking were not necessary. “This information was readily available. Either [Strang and McNeil] weren’t aware of it, and therefore they didn’t act on it. Or they were aware of it, but they didn’t act on it. Well, either way, that’s terrible.”

Part 6

Important enough to save?

The deaths at Northwood also reflect what Nova Scotia chose to prioritize in the earliest days of the pandemic. Hospital beds were cleared and PPE was stockpiled in anticipation of a rush of admissions to acute care.

But by the time the deaths began at Northwood, it was already clear that the circle of protection was needed elsewhere. On April 21, Jonathan Veale, the NSHA’s chief design officer, wrote to the COVID-19 Task Force and the health authority’s emergency operations centre: “Our planning assumption that we will face a surge in hospitals may need to be revisited as we flatten the curve and observe low volumes/occupancy in hospitals. It also appears that this wave of the pandemic will impact LTC more than hospital settings. What is the appropriate approach to caring for (COVID19) residents in LTC?”

On that day, there were 112 infected residents at Northwood, many of them gravely ill, and six had died. Outside of Northwood, there were 11 people hospitalized with COVID across the entire province, just three of them in ICUs.

“I think at the time they made a very cold calculation,” said Jason MacLean, the NSGEU president. In the first weeks of April, he was involved in almost daily phone calls with the NSHA about PPE supplies and who would have access to them; in one, he said, the government representative became so frustrated with the topic that she hung up. “I think it was based on some of the scenes they saw in Italy. And that scared the hell out of them. And they were afraid that otherwise very healthy people were about to crowd all our acute care facilities.” But, he said, a swift shift of resources and focus might have stopped the spread at Northwood. “Had they been given proper PPE from day one, it would have made a difference.”

Janice Keefe said it raises the question of whose life is seen as worth protecting. “Long-term care doesn’t get the same level of prestige or attention that acute care gets, and the people who work there are...often viewed as less-than their counterparts in acute care.”

In other words, if PPE was going to be stockpiled somewhere, it was going to be for ICU physicians and nurses, not Northwood workers. The great majority of long-term care workers, Chris Parsons pointed out, are female and racialized; many do not have permanent resident status in Canada. Most infected Northwood residents were not transferred to the emptied hospital facilities, even though these were well-stocked and prepared to isolate infected patients. “No one said, ‘We’re moving these people out of the facility into these COVID units,” Parsons said. Surgeries were canceled, people were discharged early—all measures that had serious repercussions for population health—but most sick residents in Northwood stayed there. “Why did we empty out the hospitals, if when people got sick, we weren’t going to put them in?”

"I think at the time they made a very cold calculation.” —Jason MacLean, NSGEU president

tweet this

And then there is the question of who lives in Northwood—a largely working-class population, the majority of whom are women, many of whom are African Nova Scotian, as Evelina Upshaw was. How much did that factor into the decision-making about what to prioritize, even subconsciously? Her daughter Debi wonders how much it had to do with the time it took the province to declare Northwood an emergency. “That’s what we don’t understand: Our parents weren't important enough to save their lives?”

Linda Carvery said she doesn’t want to believe that her son—her Black, disabled son—was not worth saving. “You don’t want to believe that, but society tells me that, and I’ve felt that in the back of my mind for a long time,” said Carvery. “It’s not a good feeling to have. But if you look around in society, that’s what you see.”

Part 7

Searching for answers

Erica Surette spent May trying to decipher how her mother—her physically healthy, 65-year-old mother who loved drives to Peggys Cove and a trip to the mall—could have died of COVID. She wanted to know why her mother was moved into a double room just as the virus arrived in the province. Who made that decision? The floor where her mother lived before COVID entered the facility was the last to have an outbreak. Would Patricia West still be alive if she’d been left there in her single room?

Frustrated with the lack of answers from Northwood, she turned to Wagners, a personal injury law firm, which on June 1 announced a proposed class-action suit. The family of every resident who died is de facto included unless they opt out. “Northwood Halifax had full knowledge of the dangers and health risks posed by a COVID-19 pandemic to which its Residents were uniquely vulnerable; yet, they made the conscious decision to maintain the status quo at the cost of numerous individuals’ safety and their lives,” the Statement of Claim says. The suit initially named Northwood Care Group Inc.; three weeks later, it was expanded to include the government of Nova Scotia for allegedly failing to ensure the safe operation of the facility. The suit has not yet been certified as a class action.

Kate Boyle, a lawyer working on the suit, said the 33 families who have asked to join so far are not seeking to punish Northwood. Their goal is “preventing this from happening to anybody else in the future so that their family members didn’t die in vain and nothing is done to protect the current residents there,” she said. The suit may well be settled before it reaches a court, but if it does, a judge might have some sympathy for the argument that Northwood’s administrators were grappling with an unknown contagion. But, Boyle said, a judge would also be aware of what was known: “Nova Scotia was the last to be hit, because [COVID] moved west to east; it was known that physical distancing was required and necessary; it was known that personal protective equipment, especially for the staff providing treatment to elderly individuals, was important. It was known what could be mitigated: restriction of visitors, those types of things.” There is clear evidence, she said, “that not everything was done to take reasonable care to prevent the spread of the COVID-19.”

Other families pushed the province for a public inquiry. On June 30, health minister Delorey announced an investigation, of sorts. He said that Lynn Stevenson, a former associate deputy minister of health in British Columbia, and Chris Lata, an infectious disease specialist based at Cape Breton Regional Hospital, would conduct a review using the Quality-improvement Information Protection Act. The terms of the act mean the province can release only the recommendations that come out of the investigation to the public, not the findings of what led to the deaths; the recommendations are not binding. Questioned at the time, Delorey said the terms would ensure “whistleblower” type protection for people who wished to provide information to the investigators.

The review was mandated to look at whether Northwood was adequately prepared for COVID, and how timely its response was. Lata, who otherwise declined to answer questions from The Coast, said the format was used “to allow the team to work expediently.” A public inquiry would take considerably longer to stage, and there was a desire to try to make changes at Northwood before a possible second wave of COVID in the fall of 2020. But the other effect of using the act was to obscure any finding of responsibility. Jason MacLean, of the NSGEU, said the province deliberately used a type of inquiry “that is designed to protect patient privacy, in order to avoid having to be public” about accountability.

In the summer, Stevenson met with groups of eight-to-10 families over three nights at Northwood’s corporate headquarters in Dartmouth. Darlene Metzler went to speak, and came away startled by what she heard. “What stood out to me most were the inconsistencies. One family was offered, ‘You can come in and dress in PPE and say goodbye to your loved one.’ Another one was begging to go in to see their loved one and was told they weren’t allowed…There were many tears shed, particularly for that family who was shocked to hear that other people were offered to go in.”

Renee Field asked to speak to the inquiry, to share her mother’s story; she felt the whole process was hollow. “It was very obvious, everyone in that room knew…it was just going through the motions.” Lata and Stevenson made 17 recommendations, which they released in September. These included that Northwood’s occupancy be permanently reduced, that minimum standards be established for hours of care received by residents and that the province develop a robust plan for increased staffing in long-term care.

Chris Parsons from the NS Health Coalition said the lack of transparency in the process means the public has no greater understanding of who made the decisions, such as that not to transfer infected residents to hospital. “So how do we learn from how this happened? We don’t actually know what discrete decisions were made, or the structural causes of this.”

The review did not make Erica Surette feel any better. “I was enraged. What happened? Somebody somewhere messed up. Maybe it was all of [them], I don’t know. I do know my mom is gone. And now it feels as though everybody is trying to save face and cover things up…If the intention was to try to get information, you can still do both. Do [this investigation] but also do a public inquiry. For the sake of those 53 families. And if you won’t do it: do you have something to hide?”

Part 8

We’re all responsible

If Nova Scotia had acted earlier, if administrators at Northwood and the provincial health ministry had made different choices about how and when they responded—might Northwood have escaped, with a lower death toll, or with no cases at all, as it has since last June?

“We were preparing for COVID with a specific focus on long-term care, knowing very early on that these are the highest-risk environments,” Strang told The Coast. “There is a lot we know now about COVID that we didn’t know about even in the middle of last March, in April. So I think we had things in place…We had a good plan in place based on respiratory illness plans, and we adapted those plans quickly as evidence evolved through the spring.”

The skepticism from grieving families is perhaps understandable. But that perspective is shared by experts with no personal stake in what happened here. Samir Sinha, the geriatrician who tracked the COVID response in long-term care nationally, said the attitude among both bureaucrats and the public in Nova Scotia is, “‘it was tragic, but it was unavoidable.’” And while Nova Scotia may have learned a lesson from Northwood, because there were no deaths in the second wave, he said, that has served to reinforce the perception that what happened at Northwood was somehow inevitable.

“Everybody in Nova Scotia has blood on their hands. But it makes us all feel better when we tell ourselves, well, ‘We did the best we could.’” —Samir Sinha, head of the National Institute on Ageing

tweet this

It’s an assessment he rejects. Sinha argues that Nova Scotia could have acted much sooner, as other provinces did, based on the precautionary principle established during the SARS outbreak, without waiting for national guidelines on steps such as masking. “By the end of March the evidence was really clear from the CDC in Atlanta that asymptomatic transmission was a thing, for example, and the importance of universal masking. The same information that was available to our team at the National Institute on Ageing, to Dr. Bonnie Henry [in BC] and her team, was also evidence that was readily available to Nova Scotia, but somehow actions were not being taken.”

In particular, he said, Northwood was too slow to recognize the role asymptomatic spread was playing—instead treating this new virus like influenza, as if staff would be able to see who was ill—and thus too slow to implement universal testing. “I think that’s why the outbreak just kept ballooning and ballooning and ballooning in size,” said Sinha. The CDC was warning about asymptomatic cases on March 18, he said, and by March 27, it reported that 50-75 percent of people testing positive were asymptomatic. Northwood began testing “atypical symptoms” (symptoms beyond the cough, fever and aches then associated with the virus) on April 11. The facility announced it would be testing all residents, including those who were asymptomatic, only on April 22.

There are other questions: Did residents of Northwood die of COVID before testing began? Did residents have hastened deaths, of causes other than COVID, because of the staffing shortage? The Canadian Institute for Health Information found a dramatic drop in transfers of residents of long-term care facilities to hospital, and an overall decline in care, in its study of the first wave of the pandemic.

The “we did the best we could in a difficult situation” narrative is “an easy way we lie to ourselves to make ourselves feel better,” Sinha said. Collectively, we’re letting the lie stand, because we’re all responsible. “Every Nova Scotian was responsible for the fact that they [elected] governments that long neglected the provision of long-term care in that province. And frankly, everybody in Nova Scotia has blood on their hands,” he said. “But it makes us all feel better when we tell ourselves, well, ‘We did the best we could.’”

The COVID outbreak at Northwood has left deep scars, not only on the families who lost parents, siblings or children. Betsy Webb, for example, said her mother Lee survived COVID but after the chaos, isolation and fear of those months, she deteriorated mentally and no longer recognizes her daughters or grandson in photos. Cecilia Gray’s mother survived but, Gray said, her whole community has been damaged by the loss of the matriarchs of Mulgrave Park and Uniacke Square. “We were directly impacted by the loss of elders, and we couldn’t mourn as a community, we couldn’t go to them, we couldn’t see them…It was devastating,” said Melinda Daye.

Since her son Derrick died, Linda Carvery has not been able to bring herself to go back into Northwood to visit her mother, Margaret Gordon, who will turn 100 in a few months. She believes that the qualities that made Northwood so special before—its feel of a buzzing little “mini-city”—will never come back. “It’s been free-flowing, beautifully,” Carvery said. “But can we continue to operate like that with such a fragile and vulnerable population?”

Chris Parsons fears that the fact that Nova Scotia has managed, through other effective public health measures, to dodge most of the pandemic means that what happened at Northwood will be written off as an aberration. “Because there were relatively few deaths compared to other provinces, I am worried that we’re going to just sort of move on as if the long-term care system was not already broken before this,” he said. “The reckoning that has been forced by the carnage in long-term care in Quebec or Ontario may not happen here…But we don’t resolve any of these things if we only think about it as Northwood. We solve them if we think about it as a system where Northwood became the worst case of what could have happened [everywhere].”

Northwood has been promised 144 new beds located at a new facility to be built in Fall River—100 to replace spaces removed from the north end facility, and 44 new ones. Northwood would not confirm its current occupancy or how many residents are back to being in shared rooms. Last September, the province warned long-term care facilities that had reduced occupancy during the pandemic that they must fill most of those beds (to 97 percent occupancy), or else lose funding. Currently, there are 1,500 people waiting for a placement in a long-term facility—the equivalent of more than three Northwoods, at its pre-pandemic occupancy level.

In March the provincial government newly headed by Iain Rankin tabled a budget which it said included significant new spending for long-term care. Chris Parsons calculated it was an increase of about 16 percent over the $612-million budgeted in 2020-21—but that it’s unclear how much is investment in permanent changes to long-term care versus temporary, pandemic-related spending. The budget contains $10.3-million for hiring “long-term care assistants” (a job classification that in terms of pay, training and responsibility, ranks below CCAs); these were recommended by the 2019 long-term care review panel headed by Janice Keefe as a stopgap while more CCAs were recruited and trained.

There is also $3-million for recruitment, retention and training of CCAs and licensed practical nurses, and $6.4-million for “allied health care”—roles such as recreation therapists and physiotherapists. And there is $8.6-million to start a multi-year plan to replace or renovate seven nursing homes and add 230 beds across the province by 2025.

All of this is a response, of a kind, to what happened in those six terrible weeks last spring. It may help those who live in long-term care today, and those who require it in years to come. It does nothing to provide answers for those families marking a painful anniversary this weekend.

In the year since her adventurous, irascible father Gerald died, Darlene Metzler has been trying to make sense of what happened, trying to understand who made the decisions about her dad’s care, and his last days. She would like to think that someone in government, or at Northwood, was thinking about what happened to her family, and recognized it as a tragedy.

“I don’t know if it’s because they feel like if they say they’re sorry, that they’re accepting responsibility,” she said. “But we’ve never once heard from somebody even so much as, ‘We’re sorry for the loss of your father.’”