It’s been one year since the mass shooting in Portapique. Across the province, communities and families are taking time to remember the 22 lives that were violently and prematurely taken in an act of misogynist violence.

Over the past year we have all struggled to make sense of this violence, the loss of innocent lives and the appropriate pathway forward towards healing. For some of us, the lurking sense of vulnerability to violence and danger in the aftermath of this act is a new and frightening reality that we must come to face. We feel it as police car pulls up slowly behind and we remember that the shooter used a replica police car in order to stalk and gain access to at least one of the victims.

For others, in particular women and girls who have lived with the daily reality of violence and abuse in their homes, the one place where safety should be guaranteed, this fear is not new. For Indigenous and Black Nova Scotians, the threat of violence at the hands of people in police cars or uniforms is familiar and distressingly commonplace. This violence came to the attention of the broader public multiple times in the past year with the police-involved deaths of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Chantel Moore and Rodney Levi, as well as in a recent viral video of a Halifax police officer screaming, “I will fill you full of fucking lead!” as he points his gun at an unarmed Black male.

But why should we see any connection between last year’s mass shooting by a man who only pretended to be a police officer and the violent altercations involving actual police officers? Because all of these incidents, regardless of the source, are acts of white, male entitlement.“The police have never really been a beneficent force for good. This is the reason why, as an institution, the police forces are continually able to attract men with a superiority complex.”

tweet this

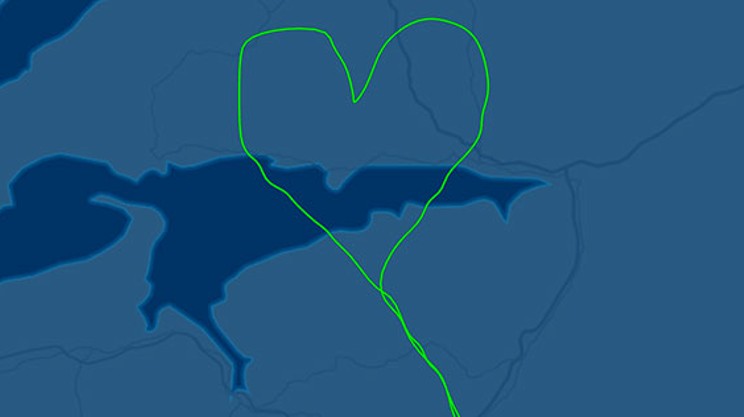

The Portapique murderer was attracted to the uniform, the car and the memorabilia because it made him feel powerful and superior to those around him. What is the police man if not a symbol of authority, an arbiter of justice positioned above the communities below that remain helpless and in need of guidance and protection? In this way, the symbol of the police officer is a little like Batman.

However, this symbolism is a powerful fiction that hides the reality of structural violence that our very country was founded on. We should not forget the role of the RCMP in quelling Indigenous and Metis rebellions in the west, and in kidnapping Indigenous children from their homes and families in order to place them into residential schools. We should not forget the role of the RCMP and other police forces in violently suppressing labour movements, including the coal mine strikes in our own province.

The police have never really been a beneficent force for good. This is the reason why, as an institution, the police forces are continually able to attract men with a superiority complex, men who believe in violence as a means of solving problems, men like the mass murderer of a year ago whose high-school yearbook described him as aspiring to be an RCMP officer.

Indeed, over the past year we have seen disturbing revelations of rampant sexual violence within the RCMP and a total lack of accountability within the system. Allegations of a workplace culture that supports widespread misogynist, racist and homophobic attitudes have also come to light. This is the same organization that has fought tooth and nail over the past year to keep information about the mass shooting out of the public eye, by repeatedly denying and redacting information in Freedom of Information Requests put forward by journalists, even taking these claims to court.

The RCMP has yet to offer any clarification regarding the nature of existence of the Portapique shooter’s relationship to the RCMP. They also have yet to offer a clear explanation into how he gained access to their uniforms. They have been frustratingly tight-lipped about much of the information surrounding the events, as well as their response to the violence, including the shooting of a fire hall in Onslow as terrified fire fighters crouched for safety inside.

Over the coming year, the families of the victims and members of the public will have the opportunity to participate in the Mass Casualty Commission leading the public inquiry into the events of April 18 and 19. The Commission’s mandate includes an inquiry into the “causes, context, and circumstances giving rise to the April 2020 mass casualty,” including, “the role of gender-based and intimate partner violence.” However, none of the commission team includes experts who are able to provide an intersectional feminist analysis of misogynist violence. In fact, 11 members of the 27-person team are current or former police officers. Given what we know about the problems of misogyny, racism and sexualized violence within police institutions in Canada, it is difficult to have confidence in the existing process.

Even the language of the commission is frustratingly vague. A quick Google search of the term “casualty” brings up the following definitions: 1. a person killed or injured in a war or accident; 2. a person or thing badly effected by an event or situation. And while this language might be technically accurate, it is far too vague and misleading to describe the events of April 18th and 19th, 2020. The innocent lives taken that day were not the result of an accident, an injury or an act of war, they were victims of a mass homicide spurred by misogynist anger and abuse.

The 22 victims were deliberately killed in a premeditated act of violence that spanned several hours, by a man who hours earlier had tortured, hand-cuffed and threatened to kill his female partner. She later told police that she felt guilty for the shooting because she had escaped and hid in the woods and feared that he had gone looking for her, killing people and burning down homes where he thought she might be hiding. Casualty is not the right word to describe this horror.

“Those who have survived or witnessed male violence in the home, and those familiar with police violence, know that these events are part of a broader violent culture in Canada invisible to those privileged enough to have never encountered it.”

tweet this

Feminist activists and advocates from across the country have repeatedly asserted that “femicide” is a term that better encompasses the events of those two days. There are several reasons why this is true.

The incidents began with acts of extreme violence against the shooter’s spouse, violence that likely would have led to her death had she not managed to escape and stay hidden. The shooter was motivated to commit this violence against her out of a misogynist sense of ownership over his partner, including jealousy and a long history of coercive and controlling behaviour towards her. She told police she was terrified to leave him because he frequently made threats about killing or hurting her family members—a tactic commonly used by abusive men to exert control over their victims.

In their 2020 report #CallitFemicide: Understanding Sex/Gender Related Killings of Women and Girls in Canada in 2020, the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability outlines some of the common characteristics of femicide, that differentiate this particular form of violence from homicides where men are the primary victims or targets.

We know that victims of femicide are more likely to know the killer and be in an intimate or family relationship with him. We know that victims of femicide are overrepresented in rural areas—men are more likely to be killed by men in large urban centres—and rural femicide is more likely to occur with a firearm.

All of this research tells us that the Portapique gunman’s violence isn’t unique to the Portapique gunman. It’s part of a larger pattern of femicide in Canada.

Those of us who have survived or witnessed male violence in the home, and those of us familiar with police violence, know that these events are part of a broader violent culture in Canada invisible to those privileged enough to have never encountered it.

We must start to challenge the culture that offers entitlement and a sense of superiority to men, particularly white men, who see themselves as the unique bearers of an objective truth. We must listen to women and to all marginalized people in order to uncover the systemic oppressions that keep them at the bottom of the social, economic and political hierarchies.

We must challenge the idea that violence—in the hands of an individual man, or state-sanctioned when wielded by the police—is a productive solution to any of our social problems. Violence is never a solution.

Johannah Black works as the Bystander Project coordinator at the Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre and Sexual Assault Services Association. She also teaches Introduction to Women’s and Gender studies at St. Francis Xavier University. She is one of the founding members of the Nova Scotian Feminists Fighting Femicide collective that came forward in the aftermath of the mass shooting to offer a feminist analysis.