It was a police emergency like few others. A man, possibly armed with a sword, had broken into a house and was fleeing the scene in a canoe on the Northwest Arm. Two police cars arrive at the Armdale Yacht Club, the officers inside looking to hitch a ride on a boat so they can bring the canoe caper to an end.

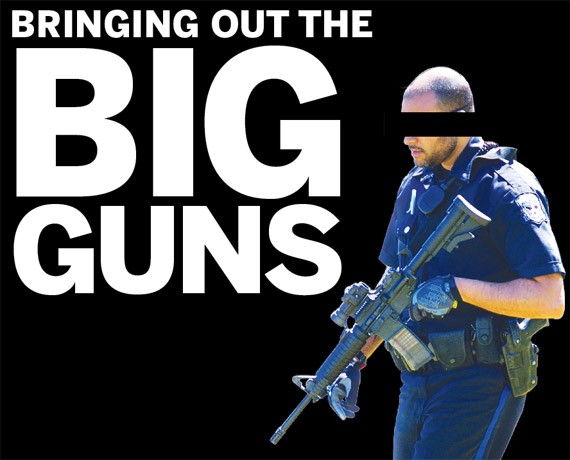

Before boarding the cops open the trunks of their patrol cars and take out their C8A2 semi-automatic carbines—a soldier’s weapon—and sling the rifles around their chests. Mark MacNeil was heading for his sailboat that October morning in 2014, when he saw the boat carrying the heavily armed officers.

“It was surreal,” said MacNeil at the time. “I have never seen police carry that kind of weapon before. I wondered what the hell was going on that those kind of guns were needed.”

The man in the canoe was Caleb John Lohr. In the weeks to come the media would report that the 21-year-old had a history of psychosis.

But sitting in that canoe weeks earlier, Lohr couldn’t have known that Halifax police were deploying a powerful, deadly new military-type weapon against him. The C8A2 delivers a bullet at more than twice the speed of sound—its high-velocity impact shearing bones and destroying surrounding tissue as a lethal shock wave travels through the body. A sword is no match for the C8A2. It’s a long-distance killer. Trained officers can pick off a pumpkin at 300 metres.

The incident on the Arm ended with an arrest and no shots fired. Lohr’s body would be found near Cape Split a month after the October 29 incident, the man having apparently slipped during a hike.

Roll forward to Remembrance Day 2015 at Halifax’s Grand Parade. Thousands of people witness police officers in tactical uniforms carrying the C8A2 carbines as they stroll through the respectful crowds gathered to honour Canada’s fallen soldiers. It’s a very public display of the new heavy weapons uniformed police officers are carrying in the trunks of their cars.

Putting these guns into the hands of the police comes at an odd time. Crime in the municipality has been decreasing steadily over the past decade, and crime across Canada is at its lowest level since 1969. From 2011 to 2014 there were only three instances where Halifax Regional Police fired a gun at a person in the line of duty. Most of the time, triggers were pulled to euthanize injured deer hit by trucks.

None of this has stopped HRP from joining the North American police arms race to acquire weapons usually found in a war zone.

Over the past 36 months, the department has tripled the number of heavy arms in its arsenal. Police say that equipment is necessary to prevent gun violence; to thwart potential terrorism; to stop another Moncton. Tactically it’s intimidation over de-escalation. It’s also an example of the gradual militarization of police across the continent that’s happened in places like Ferguson, Missouri and is happening now in Halifax.

The C8A2 semi-automatic (one bullet fired with every trigger pull) is not the first military style weapon used by Halifax police. A 2012 document, Firearms Transition Proposal, reveals that police have owned 15 FN Herstal P-90 carbines dedicated to “patrol operations” since 2004. Nine of those weapons were deployed in squad cars and the rest used for training. Other semi-automatic weapons were issued to the Emergency Response Team.

But there were problems with the Belgian-built P-90—misfires, hard-to-get parts and trouble acquiring ammunition. In 2010 and 2011, “safety concerns” forced the department to cancel training courses on the weapons.

The FTP recommends the C8A2 to replace the aging P-90. The C8 is manufactured in Canada by Colt, and in wide use with police departments across the country. In the Maritimes it’s also used by Saint John and Fredericton police, and the New Brunswick Power Nuclear Response Team. The gun’s 5.56mm NATO bullet is ideal for “containment and high risk situations that require a superior firearm for accuracy,” says the FTP report.

Over 120 pages of internal police documents obtained by The Coast under Nova Scotia’s Freedom of Information legislation paint a clear picture of why police want such deadly weapons, and under what circumstances they can be used. It’s all about projecting deadly force from a distance. The new weapon gives the police a much greater range, allowing an officer to take out a person 300 meters away—more than twice the distance of a Canadian football field—even if the human target is wearing body armour.

The Emergency Response Team had already selected the C8 as its weapon of choice in 2011, and so arming regular patrol officers with the same gun helped reduce training costs and allows all of Halifax’s police force to rely on the “pistol and the Colt C8 as the main deployment of firearms.” Battle-tested by the Canadian Army in Afghanistan, Kurdistan and Bosnia, the weapon’s strong link to the military was also a key selling feature.

In all, the Halifax Regional Police force now has 49 C8A2 carbines—three times the number of semi-automatic weapons shouldered by police four years ago. A total of 120 HRP officers have been trained on the weapon, meaning 50 percent of the officers on every watch are able to wield the carbine. There are also seven ERT officers assigned to a watch who have their own personal assigned C8s. Between 2011 and 2015 the police department paid just over $101,000 for the guns. At $409 per thousand rounds, yearly ammunition costs are estimated at $17,000, though internal documents do suggest the price of bullets will “decline as events in the Middle East settle.”

Moncton. Moncton changed everything. June 4, 2014 five RCMP officers are shot by Justin Bourque. Three officers die, two are severely injured.

The Mounties were simply outgunned by Bourque, who was armed with a modified Chinese M14 rifle and pump-action shotgun. If Canadian police took away one thing from the tragedy it’s this: “You don’t bring a handgun to a long-gun fight,” says Halifax Regional Police deputy chief Bill Moore.

Long guns, like the C8A2, gives police a tactical edge. It’s an edge that has driven weapons development and deployment for 2,000 years—time and distance. The greater the distance from the threat, the more time an officer has to react.

“The 5.56 round has far greater effective range (300 metres) than the 9mm cartridge (50 metres),” states the Firearms Transition Proposal, “which is very beneficial for containment and ERT operations.”

An RCMP internal review of the events in Moncton recommended the Mounties “take immediate and significant action to expedite deployment of patrol carbines” like the C8s. But Halifax police were already looking to bolster their arsenal of semi-automatic weapons well before June of 2014.

“Moncton has become the excuse for police buying these weapons across the country,” says Ottawa-based defence lawyer Michael Spratt. “They use it as a reason to justify what they planned to do anyway.”

Spratt, who graduated from Dalhousie University in 2005, is one of the people actively opposing the militarization of Canadian police as those departments purchase more and more heavy weapons. This “arming-up” is a national trend—semi-automatic carbines, armored cars, balaclavas, riot gear—all of which is changing the public face of the police.

“When police display this type of hard equipment it puts a wall between them and the people,” says Spratt. “People are afraid of it and they become afraid of the police.”

Deputy chief Moore, however, fully supports the decision to purchase and deploy the C8A2s. It’s a reliable weapon with an effective range six times greater than the standard issue police pistol. That gun can be a game- changer when deadly force is needed.

“There are going to be times when we need the C8,” says Moore. “I wish it didn’t have to happen but it will.”

The first eye-witness glimpse of the C8 for many Haligonians was at the Remembrance Day ceremony last November. Several officers had the carbine slung on their chests as they walked through the Grand Parade. Spratt says the debut of the weapons on such a solemn occasion shouldn’t come as a surprise. “When they spend all this money on this gear, they are going to use it.”

There are strict HRP regulations on when the C8s can be deployed, but did that Remembrance Day version of open carry really fall within the rules? Perhaps, perhaps not, says Moore. The decision to have officers openly display their weapons was made by the tactical officer in charge that day. That officer felt that if something did happen that required the weapons, police would be forced to leave the area and get the carbines out of storage in nearby vehicles—a waste of valuable time in a crisis situation.

But there’s no provision in the department’s own rules to deploy the C8 as a preventative weapon when there is no specific threat. In fact, the department’s C8A2 training manual makes it clear that use of the semi-automatic carbine “should not be considered routine.”

Moore acknowledges the carbines should only be brought out when there is “credible threat” to the public or officers. While he says there is always a “broad” standing threat to police and military people, he admits that on November 11 there had been “no specific credible threat” received by police. And yet the decision was still made to carry the loaded weapons in a large crowd of people. Speaking to the Board of Police Commissioners later in December, chief Jean Michel-Blais said the intention of displaying the C8s during the Remembrance Day ceremony was not to intimidate the general public, but to intimidate those wishing to cause harm to the public. If the public did feel intimidated that was just collateral damage.

“I am not going to second-guess that decision,” says Moore. “I understand both sides. People don’t want to see the C8, but it was a tactical decision.”

The HRP C8A2 Carbine Operator Manual is 93 pages long and details—with some redactions in the copy reviewed by The Coast—the circumstances under which a police officer can open the trunk of their squad car and remove the semi-automatic weapon.

Only those who have been qualified by the Training Section are authorized to carry the carbine and the qualified officer must be re-certified bi-annually. The manual’s “lethal force” guidelines were also redacted in the copy reviewed by The Coast, but the book’s very specific on “the role of the patrol carbine.” The semi-automatic rifle can be put to use when dealing with barricaded persons, hostage incidents, IARDs (“immediate action rapid deployment”) and armed suspect incidents where there is an immediate need to establish a perimeter before the arrival of ERT.

Every time an officer “utilizes” the carbine, a Subject Behavior Officer Response form must be filled out. But there are no easily available statistics on how often officers have removed the carbine from their patrol cars. An SBOR wouldn’t be required if the officer accessed the C8 from the trunk of the vehicle and had it at the ready but didn’t fire it, says a statement from HRP. Halifax police have only fired the C8A2 once in an operation, during a March 2013 weapons call. No one was hit or injured during that “ballistic force” event.

“Proper considerations must be exerted when choosing to deploy the patrol carbine in a public environment,” reads a simple, stark direction to police in the manual. “But in a nutshell, here is the basic guideline. The patrol carbine should be deployed anytime [there is] considerable risk of great bodily harm or death.” Here “anytime” is defined as containment situations, active shooters, a commercial robbery in progress, high-risk traffic stops, serving warrants when the person could be armed and dealing with vicious animals.

But the police aren’t the only ones armed. Though crime is down overall, the last few weeks have seen a rash of guns in the news. This past Tuesday RCMP arrested two youths after finding a bag containing several firearms near Millwood High School. That was the same day as the funeral for 20-year-old Joseph Douglas Cameron, who was shot and killed on a Woodlawn sidewalk on March 29.

Someone working independently of police to stop gun crime in HRM is Mel Lucas, project manager for Ceasefire. The intervention organization tries to prevent youth from engaging in violence through de-escalation, not intimidation. Lucas wasn’t aware of the new police weapons, but is familiar with their reputation in other cities.

“I look at them as a tool. There may well be incidents where the police need them,” he says. But HRP should control the use of the carbines carefully, Lucas adds. If the weapons start being used in everyday policing situations—call that mission creep—then that could send the wrong message to heavily-policed communities.

“It could put people on the defensive. Some individuals might feel threatened or scared.”

Michael Spratt is more blunt. The militarization of police weapons and tactics will likely keep ratcheting up in Canada, he says, until it’s a white face in the crosshairs.

“When a white kid in a wealthy neighbourhood is shot dead by police using one of these weapons, things will change,” he says. “It’s sad to say, but at that point people will say ‘Enough, enough of this.’”

Two days after Remembrance Day last year, 130 people were killed in a coordinated series of terrorist attacks in Paris. It’s hard to argue that police shouldn’t arrive at the scene of events such as that—or more recently the airport bombings in Brussels—without semi-automatic carbines at the ready. Spratt doesn’t disagree, but says the weapons, as we have seen in Halifax, start to creep into daily use. That keeps the police separated from the citizens at a time when a free flow of information between the two may never have been more important.

Police budgets across Canada have soared in recent years while crime plummets. Yet rare, spectacular events like Brussels or Paris or even Halifax’s Valentine’s Day 2015 mall murder plot are used to justify the acquisition of heavy weapons by police.

The HRP made the decision to buy the C8 all on its own. Because the carbine was a replacement for the old P-90, the department wasn’t required to get permission from the police commission or city council; it was simply an internal decision with no public or political input. And that unilateral decision by the Halifax police to dramatically increase its semi-automatic weapons stock is a problem, says Spratt.

“The lack of oversight here is troubling. There is not enough on what police do and how they do it.”

Police brass though are proud of the department’s community policing philosophy. It’s a cornerstone of how they see themselves and how they operate. Bill Moore says the department is painfully aware that events such as the overwhelming force used against citizens in Ferguson and other US cities has galvanized public concern about police militarization.

“We don’t want to be soldiers. This not a war zone,” says Moore.

True enough. But last year at Grand Parade it may have been hard for some people to believe that. Ordering officers to wander through a peaceful crowd carrying carbines and wearing tactical clothing is a mistake, says Spratt. He believes money and effort would be better spent on mental health and community support services, rather than turning cops into soldiers.

“This equipment keeps people away from police because that’s what it is designed to do. It sows mistrust.”

The most chilling section of the cops’ training manual for the C8s is the matter-of-fact, clinical way it deals with effects of the gun’s bullet on the human body. Travelling at 2,611 feet per second—that’s more than twice the speed of sound—the bullet causes “disruption of the tissue far greater than that experienced with [a] handgun bullet.”

When it strikes a person, the energy from the bullet is transferred and creates “a shock wave capable of tearing and shredding living tissue.” This creates a “temporary cavity” that’s further “enhanced” as the bullet fragments in the body and lacerates more tissue and organs.

But even then, there’s no guarantee an individual would go down with a single shot, warns the manual: “Police officers must realize the limitations of their firearm and be prepared to fire and strike a subject repeatedly until the threat is stopped.”

And there is lots of opportunity to keep firing; the carbine’s clip holds 25 bullets. The C8A2 is designed to kill. It’s designed to intimidate. That, after all, is why the police bought them.

Rob Gordon has covered defence issues and general news for CBC, newspapers and magazines for more than 30 years. He has been embedded with the navy in the Arabian Sea, with the army in Afghanistan and occasionally works as an associate producer for the CBC's fifth estate.

Update: At 5:01pm on Friday HRP sent out the following media release regarding this article. It was also posted in our comments below, but we’ve pulled it out and put it here for emphasis and reader convenience.

“We strongly agree that police shouldn’t become militarized. That would go against the way in which we strive to connect with and serve our community.However, we must be prepared to protect our community, including during weapons incidents, whether that’s a person barricaded in a house with a long gun or a group of people plotting a mass shooting. We believe our citizens expect us to be prepared to effectively and efficiently handle these high-risk situations. We also we also have an obligation to our officers under the [Nova Scotia Occupational Health & Safety Act] to ensure they’re adequately equipped and trained to do their jobs.

The article is correct when it says we were planning to purchase the C8s prior to the tragic situation in Moncton. In fact, we’ve had carbines at HRP since the early 2000s. We’ve tripled our armament over the last four years and here’s why:

•We replaced outdated firearms (shotguns and P90’s) from the early 2000s.

•We increased the number of firearms available in our Training Section to prevent us from removing operational firearms from the frontline when conducting training.

•We equipped 14 additional Emergency Response Team (ERT) members with C8s when we enhanced our ERT deployment strategy in 2014.It’s also worth noting that:

•Our deployment model for long guns has remained largely unchanged since their introduction within HRP about a decade and a half ago.

•Outside of ERT, only select officers on each shift are specially trained to access and use the C8s.

•Our approach is in step with other police agencies across the country.

•The C8 is just one tool in our tool kit to be used in certain circumstances and in concert with less lethal tools. It also involves strong oversight.It may be shocking for people to grasp that the incidents we’re seeing around the world (San Bernadino, California; Paris; Brussels) and closer to home (Mayerthorpe, AB; Ottawa; Moncton) could happen here in Halifax. We’ve been very fortunate to date that we have averted several significant incidents where people have had the ability and intent to do serious harm to many citizens in our community—the planned mass shooting at Halifax Shopping Centre in 2015 is one example. It’s a sad, stark, cold reality. Unfortunately, we don’t control the people intent on doing harm to others and we must be prepared for such high-risk situations—our approach is based on need, not want.

Police work by its nature requires police agencies to prepare for the worst and hope for the best. With that in mind, our officers must be adequately trained and equipped for their own protection and that of our community.