Decked out in leather vests and black hoodies, the Soldiers of Odin are spreading their message of white nationalism on the streets of Halifax.

At least, they were up until a couple of weeks ago.

The Nova Scotia chapter of the far-right Soldiers of Odin network disbanded earlier this month over disagreements with the mother chapter in Finland.

Speaking over Facebook messenger, former president Billy Rushton would only say the quarrel was more about financials than ideology. The father of two from Amherst says he’s starting a new charitable organization to replace the Nova Scotia SOO, which will feature many of the same members, if not ideas.

Soldiers of Odin, a loose-knit international organization dedicated at its core to “protecting” white culture, has carved its name across Europe and Canada over the past few years. It’s one of the more visible battalions in a new crop of far-right extremist groups emboldening hate and radicalizing white Canadians. The group’s use of street “patrols” are a concrete reminder of their views, acting as an intimidation tactic towards immigrant, refugee and Muslim communities. These are the people who don’t want you here.

Nova Scotia’s Soldiers of Odin chapter sprang to life on June 1, but only over the past few weeks has the group come to the attention of Halifax residents. Last month several of the local SOO’s 11 members began walking the city’s streets, wearing branded merchandise and boasting of their activities.

Anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant rhetoric is nothing new online, and racism in Nova Scotia stretches back centuries. But the Soldiers of Odin and its ilk represent an organized path to normalizing hate speech. Its existence is the wellspring from which intolerance proliferates like cholera. The presence of its proud membership on the city’s street, a potential threat to the peace.

“Discrimination against Muslims is called racism,” reads one image the local SOO shared on its Facebook. “Muslim discrimination against others is called Islam.”

Another photo was more concise, simply captioned, “Fuck Islam. This is Canada.”

“‘Fuck Islam?’ That means nothing to me,” says Rushton. “I don’t see that as being racist. I see that as stating a view.”

Mimicking the clothing of motorcycle clubs and adopting Norse iconography as an identity, the Soldiers of Odin formed three years ago in Finland as an anti-immigration group of far-right radicals. Its white membership was responding to a wave of refugees, many of them Muslim, trying to seek shelter from civil war and genocide.

In Canada, the SOO and similar groups began to form after Justin Trudeau’s 2015 promise to help resettle 25,000 Syrian refugees. Donald Trump’s victory the following year only poured gasoline on the fire.

The unifying thread between the Soldiers of Odin and other groups like the Proud Boys or III% is a nationalism fueled by racism, xenophobia and an urge to protect what they narrowly consider to be Canadian values. Online and in real life they offer a safe space for racism; somewhere where it’s OK to be a white supremacist.

Outwardly, though, the SOO members present themselves as invested in charitable work. They give out pizza to the homeless, praise veterans and pick up litter. Entry-level acts of kindness that mostly serve to downplay their extremist beliefs.

“It’s like if the KKK shows up and tries to hand out blankets and open up a soup kitchen,” says Evan Balgord, executive director of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network. “You don’t celebrate that because of what it ultimately represents.”

Balgord says the first iteration of the Soldiers of Odin in Canada had many obvious ties to neo-nazis, but the network splintered last year over disagreements about whether to remain loyal to Finland. The founding chapter has strong Nazi sympathies and doesn’t shy away from violence. Its president was convicted for a racially motivated assault back in 2005.

Before it was shuttered, Nova Scotia’s Soldiers of Odin proudly claimed on its Facebook that it was “Finland approved.”

Point blank, Rushton says he is not racist. In no way, shape or form does he feel hatred towards another race. What he is bothered by, he admits, are the “demands” immigrants are making on Canada’s culture. The national anthem was changed to be gender-neutral, he points out. Statues are being torn down to better reconcile Indigenous history. Never mind that neither event has anything to do with immigration, they’re still examples he lists of how newcomers are spitting on Canadian values.

“I’m not saying these specific things may have come from immigrants, but immigration sure had a push to it.”

The absurd rhetorical lengths far-right groups will go to claim they’re not racist even while explicitly making racist remarks is a familiar tune to Barbara Perry. A professor of criminology at the University of Ontario’s Institute of Technology, Perry’s written extensively on hate crime and researches extremist groups in Canada.

“They will adamantly deny that they’re racist in any way,” she says. “Yet you only have to take a quick look at their websites, typically, or their Facebook presence and you find the exact opposite.”

Let’s take a quick look, then. In July, the Nova Scotia SOO chapter posted a status update on its Facebook blaming the Humboldt Broncos bus tragedy on “diversity” because Jaskirat Sidhu, the truck driver who caused the accident, moved to Calgary from India in 2013 on a student visa. Two days later, the group shared a fawning video documentary from Russia Today about the Soldiers of Odin, entitled “Neo-Nazi or True Swedish Patriots?”

Individual members are just as blatant.

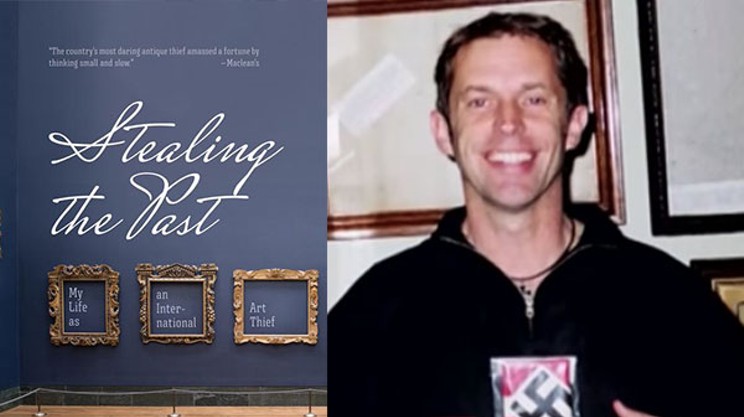

Several regularly post violently anti-Muslim comments and white supremacist imagery. One of the more aggressive voices in the local movement, Dartmouth member Norman English, has a photo on his personal Facebook of a handgun and an assault rifle proudly displayed next to a Confederate flag. English did not respond to a request for comment.

The undisguised racism was enough for Murray Bauer to walk away from the

Soldiers of Odin completely.

A veteran of the Armed Forces and a commissionaire, Bauer was one of the people involved in Rushton’s Nova Scotia chapter before leaving due to the group’s beliefs.

He says he came across the SOO online and was attracted to its more innocuous public goals of championing veterans and supporting Canadian heritage. Over the course of several weeks, he went from curious Facebook fan to being named as the chapter’s vice president. By that point, he was already feeling uncomfortable with the racist imagery other members were sharing.

“It sort of kept building up and building up,” Bauer says. “Finally I just came to the point, ‘No, sorry.’”

Last month he cut off all association.

“To turn around and say one group of people is less than any other group of people, that’s not me,” says Bauer. “I don’t believe in that.”

Perry says it’s common for these far-right groups to try and find some non-threatening hook to draw in new members. Sometimes that’s music, sometimes it’s an interest in military history. It can even just be camaraderie—a sense of belonging. Over time, the recruits get exposed to more and more radicalized ideas.

“It’s not necessarily a linear process and it’s not an immediate process,” she says.

For many, that’s their cue to exit. Perry says she’s come across plenty of people who, like Bauer, join the SOO or another group unaware of its true nature and leave shortly after being exposed to its radical underbelly.

One of her current research colleagues spent years as a recruiter high up in the skinhead movement. The violence of that world drove him out, she says.

The threat of violence is also very real when it comes to the Soldiers of Odin. A 2017 intelligence bulletin from Border Services stated some members of the SOO “are not afraid to use violence to achieve objectives.”“Whether there’s violence or not, the street patrols themselves are a form of violence and intimidation. They’re intended to keep people silent.”

tweet this

“Show your true patriot blood,” reads a Facebook update from the Nova Scotia chapter back in August. Below the words is an image of the SOO logo over a skull and pistols, flanked by the Arabic script for “infidel.”

“This is our future,” says the post. “We won’t back down. We will stand up. We will be heard.”

Members see the call to arms as one of self-defence. Rushton, who claims to have many Muslim friends, blames the religion for terrorism events the world over.

“I mean, look at the [United Kingdom] right now,” he says. “If that is not enough to show Islam is full of hatred, then I don’t know what will. Like I said, in no way am I racist.”

It can’t be racist if it’s the truth, he claims. He’s wrong, on multiple levels, and not the least because, statistically, Canadians have far more to fear from the Soldiers of Odin and their brethren than Islamic extremists.

A 2015 study by Perry and her colleagues found that between 1980 and 2014 there were over 120 incidents of violence in Canada from far-right extremists, ranging from attempted assassinations to fire-bombings and shooting sprees.

“During the same period of time we found about seven incidents associated with Islamic extremism,” says Perry. “So, it’s just not true that there’s a greater risk associated with Islam in the Canadian context.”

Her research echoes similar findings down in the United States, where the Anti-Defamation League’s Centre on Extremism found that right-wing extremists and white nationalists were responsible for 59 percent of all extremist-related fatalities last year.

Since 9/11, white supremacists and other far-right extremists have killed more people in America than any other category of terrorist.

Tragically, recent examples are plentiful. Just days after one far-right terrorist in the US was found mailing bombs to journalists and politicians late last month, another anti-semitic extremist killed 11 worshippers at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh.

Canada isn’t far behind. Two years ago Alexandre Bissonnette shot and killed six and wounded 19 others at a Quebec City mosque. Four years ago, the anti-government, pro-gun radical Justin Bourque killed three RCMP officers and severely injured two others in Moncton. This past summer, Matthew Vincent Raymond shot and killed four people, including two police officers, in Fredericton. Raymond, it would emerge, had recently been barred from a local coffee shop for his rants against Islam and Syrian refugees.

Nova Scotia hasn’t seen that sort of deadly violence, but that doesn’t mean the sentiment behind such bloodshed isn’t already rooted deep in our history. As noted by the Toronto Star, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service traces far-right violence in Canada all the way back to race riots in Nova Scotia in the 1780s. A chapter of the Ku Klux Klan openly held rallies and recruited members in Halifax in the mid-’90s. After 9/11, Muslim residents who had lived here their whole lives were threatened, harassed and assaulted. Last summer, the alt-right Proud Boys confronted an Indigenous protest during Canada 150 in defence of the group’s perverted version of Canadian “values.”

It bears mentioning as well that the closest Halifax has come to an act of deadly terrorism was the mall shooting plot planned three years ago by Columbine-worshipping, neo-nazi fans.

Even just the spectre of violence from these groups is a real threat to those communities who know they’re being targeted, says Perry.

“It’s very intimidating,” she says. “Whether there’s violence or not, the street patrols themselves are a form of violence and intimidation. They’re intended to keep people silent.”

Growing up in Halifax, Masuma Khan is certainly familiar with Islamophobia. She watched her parents suffer attacks from white Canadians who didn’t think her family belonged. She regularly hears from other members of the Muslim community who have been yelled at, called terrorists, made to feel alienated in their own home.

“In the Muslim community, when we talk about Islamophobia and the experiences we have, often amongst a lot of Muslims there’s a disbelief,” says Khan. “They’re like, ‘How can this be? We’re in Canada.’”

People forget hate happens everywhere, she laments.

The vice-president academic and external for Dalhousie University’s student union has herself been targeted by that hate. A year ago, Khan criticized the #whitefragility of settler Canadians upset about a symbolic DSU motion to not participate in Canada Day. It was meant as recognition of the country’s historic mistreatment of Indigenous peoples; a reminder that we are all immigrants on unceded land. For her effort, Khan was lambasted by right-wing pundits, investigated by her own university and to this day receives threatening messages and death threats.

“It hasn’t been easy dealing with all this hate, for sure,” she says. “It plagues on your mind. It pops up at times when you think you’re having a happy day and then all of a sudden you’re reminded of how much people hate people like you.”

Sadly, the climate for that hatred is getting worse.

Law enforcement agencies across North America, meanwhile, have been slow to respond to far-right extremists even as the violent fringe movement publicly brags about its activities online. Just months before the Quebec City Mosque shooting, for example, CSIS determined “there was no indication that right-wing extremists pose a threat to migrants.”

Both Halifax Regional Police and the Nova Scotia RCMP say they continue to monitor organizations like the Soldiers of Odin and stay informed about “trends” such as the propagation of far-right extremist groups.

“Nova Scotia RCMP is aware of this group, however, we have no active investigations involving it at the present time,” says corporal Jennifer Clarke.

The response, for Khan, indicates the bias of largely-white law enforcement agencies.

“If they had word of a so-called Islamist or Muslim terrorist group, they’d be on that like peanut butter and jelly on toast,” she says. “But because it’s people that look like them...they are not the ones being threatened, so obviously they’re not taking it seriously.”

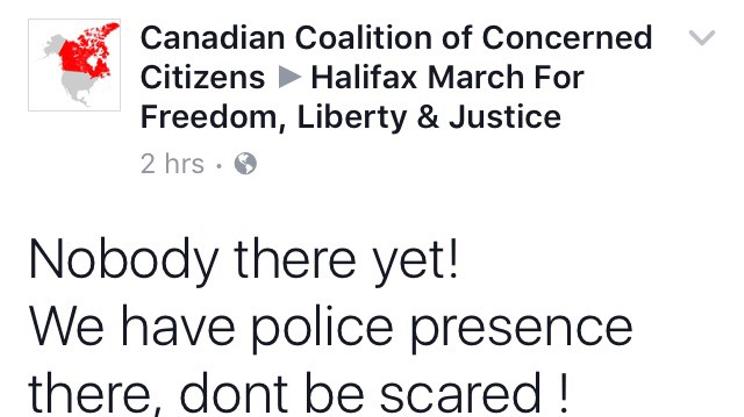

Even with the increase in far-right groups across Canada, it’s worth noting that membership numbers remain statistically minor. A joint rally of far-right groups on Parliament Hill back in July gathered fewer than 100 people. The Nova Scotia SOO Facebook page has 157 followers, many of whom are visitors from other SOO echo chambers across the internet.

On the spectrum of violence, Balgord says it’s unlikely the Soldiers of Odin or any other group would coordinate a planned attack. A more plausible scenario would be a single soldier or SOO fan who becomes radicalized and carries out the group’s message to deadly result.

“Ultimately, the root cause of these so-called lone wolf attacks is the hate propaganda,” says Balgord. “When they’re putting out content that is explicitly dehumanizing to Muslims...you know, that stuff is dangerous and we’ve seen people act on it in the United States and here in Canada.”

More broadly, the threat these far-right movements represent is a shifting of norms towards a more intolerant society.

“They’re making it more acceptable to be racist and to share those views publicly,” says Balgord.

Unless some other entrepreneur decides to start a new chapter, Nova Scotia’s Soldiers of Odin are no more. It’s been replaced by a new structure made up of the same old parts, and according to its president, strictly dedicated to charitable work.

“I don’t want to fight the racist finger-pointing anymore,” says Rushton. “I want to have a club that folks will trust and rely on.”

The president won’t confirm any of his members, nor will he disclose the name of the new group until he’s secured trademarks for the logo.

One former SOO member, however, tells The Coast that the new group is called Thor’s Knights. A Facebook page under that name lists Rushton’s Amherst phone number as its contact. Rushton disputes this and claims Thor’s Knights is an old club that was supposed to be deleted long ago, despite the page seemingly having been created just two weeks prior.

The name and the charitable undertakings don’t really matter, though. If Rushton and his membership split with the Soldiers of Odin not because of Finland’s neo-nazi ties but over financial mismanagement, Balgord says that shows something about the new group’s mission.

“We know where they came from, and they came from a hate group,” he says. “Is the rebranding, does it mean they’re a different thing? Not if they’re all the same people and they’re still doing the same thing.”

Rushton says the new club’s bylaws will include immediate dismissal for any member found engaging in racist behaviour, speaking in disgust against another race or acting in violence against a race. But that doesn’t include “announcing your beliefs” about another race, he clarifies.

The group will also not be above taking time away from its stated charitable mission to hold public rallies to spread its message.

“There will be times when we may throw a rally to show awareness against something we believe should be known,” Rushton says. “But in no way will it show hate.”

Bauer isn’t convinced. He says he wants nothing to do with the new group.

“Pardon my expression; a leopard does not change its spots.”

Even without the SOO, both Balgord and Perry say they’ll be watching the east coast more closely now as the spread of far-right extremism in Canada continues.

The best way to neutralize that hate, says Perry, is to show support for those targeted. The public can rally around Muslim and immigrant communities, letting those families know others are ready to defend them against intimidation and violence. United not by hate, but by compassion, humanity and

acceptance.

“Local mayors, premiers, these sorts of people need to be very forceful and speak out about these groups, that there’s no place for them,” she says. “There’s no place for the sorts of narratives they carry with them.”

Rushton shrugs off all the criticism. He’s unconcerned with why Nova Scotians should tolerate his new group.

“That’s on them if they choose not to accept something good,” he says. “That’s on them if they choose to hate and discourage.”