Gaby’s suicide threats had subsided since her blissful relationship with her dead husband’s former boss, John Orange. John insisted on being called Johnny to spite his thin grey hair, low hanging spectacles and Norm Drabble belly, all of which collaborated to spite his status as a principal at a prestigious law firm. But life’s cycles spun and just like Gaby’s last love and John’s last love this one dulled over dozens of full moons. By the time I met my new stepfather-in-law, Johnny Orange, Lawyer Without a Cause, he was sleeping with younger, perkier, more sober women.

Thanksgiving was to be the first official family function for these already stale newlyweds. And because Sarah and I had no intention of wasting our real Christmas watching Gaby and Johnny decorate their fast-fading love affair with worn-out tinsel, it was also the day we’d celebrate the family’s first-ever Ukrainian Christmas. From the time Gaby and her first husband, Vlad, had defected, all things Ukrainian had been banned from their household. Since Vlad’s death Gaby had taken considerable pains to revive what she and her children never had. Her traditions had been stolen by the Soviets and her children’s by their father. She intended to create a reasonably reproduced facsimile of January 7-like festivities, regardless of the date.

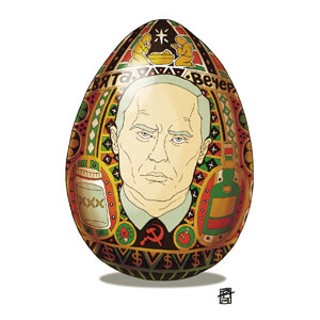

On “Christmas Eve,” Sarah, her sister Jennifer and I sat around the kitchen table painting eggs, cutting out and colouring images of Baby Jesus, Mother Mary, Vladimir Putin and gift-bearers, while Gaby fluttered around us handing out scissors and crayons and paints and sweets, in between trips to the kitchen preparing our Holy 12-course Feast of sweet meats and pastries. We ate enough to hold us until December 25, egged on by Gaby’s chants of “Eat! You’re too skinny, Sarah, eat! Not you, Jenny, you’ve had enough.”

Afterward we surrounded the Christmas tree and serenaded it with carols. Gaby explained that if Vlad hadn’t cut the family off from the local Ukrainian community, the girls would have grown up visiting Ukrainian neighbours at Christmas, bringing with them lanterns and spreading grain on their doorsteps as they sang for small gifts or donations for the church. Had that happened, and had this actually been Christmas, other people’s children would now visit and sing for us. Sarah resisted the cultural reclamation by running frequent errands outside the house. In between all those Canadianized Ukrainian traditions I found myself accompanying her to convenience stores, gas stations and coffee shops in search of last minute high-need items like sugar sprinkles, miso, bouillon cubes and new bulbs. Intermittently I would drink scotch with Papa Johnny Orange, who belted Irish folk tunes between shots and somehow still managed to feign control over the Christmas show like it was his law firm.

Jenny was mostly invisible. Her cellphone-laptop-palm pilot-and-pager filled in where the walls of her bedroom left off seven years before. She had become the president of one of the surviving Silicon Valley dotcoms and I could only assume that her motivation for being in Ottawa was the same as Sarah’s: to maintain that most precious illusion of family and avoid wasting actual Christmas there.

While Johnny and I downed scotch Gaby excreted a faint combination odour of expensive perfume and cheap vodka. We never saw her drink but Sarah and Jenny spent 60 minutes spread throughout each day pulling half-finished bottles of fermented potato snot from ceiling beams, floor panels and toilet tanks. The progression of Gaby’s morning teeters toward evening staggers were proof of a losing battle.

The pervading chill of booze, technology and an escalating meal plan made a step outside into Ottawa’s autumn air feel like a blast of tropical heat. Still, for me “Christmas” in their three-bedroom refrigerator was an Icelandic paradise because nobody ever yelled except Johnny, who was never angry but enjoyed barking orders that had already been fulfilled or were completely irrelevant. “Somebody baste that damn turkey before Butterball sues!”

“No turkey, Buddy, and the roast is ready.”

“Good girl!”

The hostilities were precise and subtle, unlike the civil war re-creations of my Christmases past, in which all the offences of history were dragged like Scrooge-haunting ghosts through our sparsely decorated living room. This was how I thought of Christmas, but neither my sister nor I had been home to help praise baby Jesus in several years. Sarah’s family psychosis had become my own, and as far as I was concerned it was a big improvement.

Ottawa was the opposite of my origins, with its paucity of direct insults and abundance of big-ticket attempts at buying love or at least forgiveness, bunched stacked and spilling out from under the tree Canadian-style. Every year Sarah spent 300 times more on Christmas presents than on long distance phone calls, only to be outbid by her mother and sibling. This year there was even greater disparity because Step-Papa Johnny bankrolled a massive effort to win over his former employee’s distant daughters.The biggest benefactor to the whole shopping spree was the person least interested in participating: me. For my reticence I received cash, clothes, booze, books and CDs, for a return on investment that would make Arthur Anderson blush. It made little impression on the wrapping paper vultures around me, who were all so engrossed in their simultaneous shredding orgy that they failed to witness the opening of their scrupulously selected bribe. When the wrappers settled over gleaming packaging we were all smiles and thanks. There was nary a shout nor a yelp and we all had a nice buzz going by noon.

Periodically Sarah would lead me up to her childhood room and amidst the old Raggedy Anns, Barbies and Cabbage Patch Kids would spit family-oriented venom through gritted teeth. “You see the way that philandering fatty treats my mother?! How drunk is Mom gonna get? Where the hell was Jenny when she fell down the stairs?” Even these rants secretly thrilled me. With Sarah’s frustration splintered in three directions I became her best ally again, like in the days before we bought our fixer-upper house and settled into that struggle with a mundane mortality, where material things are a temporary comfort.