On the third anniversary of my mother's death I borrow a car and drive out to her grave, as I do a few times a year: Mother's Day, St. Patrick's Day (her birthday), June 20 (her death day) and maybe an odd spring or fall day. She is buried in the countryside, in a corner of a sweet small cemetery called Pine Hill, just outside Hubbards. Her grave is almost under a pine tree at the edge of some woods and I like to imagine bunnies there at night, sitting on the rusty fallen needles, peeping out from under the tree and then cavorting on my mother's grave in

And then I drive further west, along the old shore road, so I can see the twinkle of the sun on the water and get a whiff of brine every once in a while.

I have rented a little cottage

I stop for provisions. Cream (I bring good coffee beans and the grinder from town), eggs, peameal bacon, fixings for pancakes (maple syrup from town) and a big bag of peanuts in the shell (for the chipmunks). From

The cottages at Green Bay are my idea of perfect. Wood, with a tiny veranda. Two tiny bedrooms, each just big enough for a double bed made up with mismatched sheets; tiny bathroom with threadbare towels and loose, rickety taps; living room with lamps on old small side tables plus a deep soft couch and stone fireplace; kitchen with mismatched dishes and flatware, 14 cast iron frying pans and a temperamental toaster plus aluminum stove-top coffee

I have been here times before, through the years, staying in one or another of the cottages, each of which has its own name: Blueberry, Boulder, Such A Spot. Some people have been coming to Green Bay for decades. There are bundles of little journals in each cottage, and folks write things like, "Who can believe it's year 23 here? Joey is getting married and Debbie has graduated..."

The oilcloth, the coffee maker, the cutlery, the decks of cards soft and thick after so many years, all these things transport me back to childhood cottage times.

Come By Chance and Ship Ahoy are my favourite cottages, they're all great and sweet but these two are slightly more isolated. I am in Ship Ahoy, the most easterly.

I unload the car—the food provisions, some magazines, some books, binoculars, comfy clothing. Some wads of letters of my mother's.

Inside I inspect the bedrooms and take the one with the door closest to the fireplace. No particular reason, just a quick choice from the gut. Nights in Green Bay beds mean magical sleeping: Deep and uninterrupted, the smell of the pines and the sound of the waves curling over onto the beach.

I put the food away and grind some coffee. While I wait for the perk to perk I see that one of the mismatched plates is the same as my mother's good dishes, used for Christmas, Thanksgiving and company. An off-white with a small geometric design in the centre—like as if a Spirograph made organic shapes, which I suppose it does, but you know, less cosmic. I think it's called Desert Star.

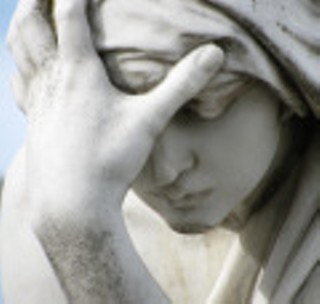

I take the coffee, a butter tart and a magazine out to the porch and my mother is there. She was 76 when she died, but her 40-year-old self is sitting there.

She is wearing the orange V-neck velveteen top I always liked, clam diggers and ancient

She has already found the picnic I made and packed into the two handled wicker picnic basket we had when I was little: Hard-boiled eggs, salt and pepper with wax paper between the tops and bodies of the shakers. Actually, everything is wrapped in wax paper: Dill pickles, even though the wax paper gets soggy, deviled ham sandwiches, tomato wedges, cookies. Potato chips. My mother grunts appreciatively as she paws through the food. She comes upon the mickey of rum and looks up at me, really happy.

"I hope you don't think you're having any," she says with a fake sneer on her face. Of

"Is there pickle in the deviled ham?" my mother asks. She peels back the top bread of a triangle of

"Whaddya take me for?" I say.

"Number one daughter," she says.

"Damn right," I say.

We snack a bit and read a bit and I go in and doze on the couch.

In the early