On October 23, the Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans made headlines when it recommended the slaughter of 70,000 grey seals over four years in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence. Senator Fabian Manning, chair of the committee, told a news conference the proposed cull was an "experiment" to see if it would help dwindling cod stocks recover from decades of overfishing. Manning admitted there was "no solid research anywhere" to support the recommendation, but he added that killing thousands of seals would allow scientists to gather information about the effects on the cod.

The reaction was swift. Dalhousie University cod expert Jeff Hutchings told the media a cull "violates all of the characteristics of an appropriately designed experiment." He also said the move would be "irresponsible" given that 20 years had passed since the cod collapsed and the government had still not come up with a recovery plan for the species.

Rebecca Aldworth, head of Humane Society International, said the recommendation "had everything to do with handouts to the commercial sealing industry and nothing to do with the protection of fish stocks." She also warned that a cull may not stop in the southern Gulf. "The Senate report recommends action should be taken on Sable Island as well."

Newly designated as a national park reserve, Sable Island sits about 300 kilometres southeast of Halifax on the eastern Scotian Shelf and is home to the world's largest grey seal colony---estimated between 260,000 and 320,000 animals, a population that had until recently been growing exponentially. There are two other lesser-known herds, also named after where their pups are born. The Gulf herds pups on ice and on islands in the Gulf and is the primary target of the recommended cull. Its population is estimated at 63,000 seals. The Eastern Shore herd whelps mainly on Hay Island---near Cape Breton. This herd is roughly 20,000 animals. In the 1970s, after more than a century of relentless exploitation for their oil and skins, only a few thousand grey seals populated Canada's east coast. Since then the species has managed to rebuild---a recovery that many would see as a conservation success story.

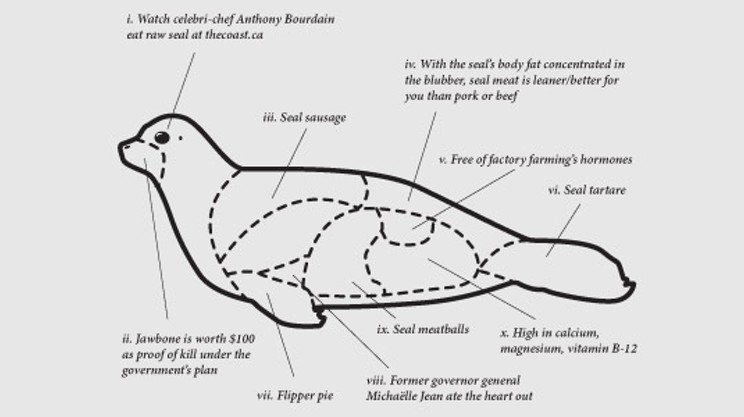

But not to the fishing industry. It has likened the grey seal recovery to "an invasion," blames the seals for the failure of cod to recover and has lobbied the DFO for a cull of at least half the seals on Sable Island---the heart of the grey seal population (See "Sable Island's cod killer?" July 1, 2010). If the Senate Committee's recommendation goes ahead, sealers could be paid a bounty of $100 for every grey seal they kill in the southern Gulf and the time of year would impact the various herds differently. A cull targeting the whelping grounds---the ice and islands where the Gulf pups are born---could result in the decimation of that herd, since the cull recommendation exceeds that herd's total population.

But if the cull were to take place year round---particularly during summer months ---then it would include seals from Sable Island and the Eastern Shore because this is when thousands of them migrate into the Gulf to feed. Up to now, the federal government hasn't bowed to industry pressure because it was not based on the available science. But this time, things may be different.

Politics in the driver's seat

In 2009, Gail Shea, then minister of fisheries and oceans, announced the closure of the southern Gulf cod fishery. The first closure in 1993---the moratorium most people think remained in place---held initially for about four years. But even during this time, cod were fished recreationally and were still caught unintentionally---as bycatch---in other fisheries. Between 1998 and 2009, commercial fishing of cod in the southern Gulf was permitted every year, except for 2003. By the time Shea shut it down, it was already too late.

Doug Swain is DFO's cod expert in the Gulf region. In 2008, he and a colleague warned that the southern Gulf cod population was doomed. This is not just true of cod---other southern Gulf fish have been overfished to dangerously low levels. The scientists stated in no uncertain terms that the population would be gone within 40 years without a cod fishery and in half that time with one.

Today, cod in Canadian waters from the tip of Labrador south to Georges Bank is teetering on the brink of biological extinction. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada partly attributes this to the fact that fishing resumed on many of the stocks not long after they collapsed.

Swain and his colleague also noticed that an unusually high number of older cod seemed to be disappearing---not showing up in the DFO's annual bottom trawl surveys as expected. Since adult fish produce the next generations, whatever was killing them was also behind the non-recovery, they argued. The scientists hypothesized that the "missing" fish could be linked to the growing grey seal herd. But this hypothesis, they noted, was "inconsistent" with the available science, which showed that cod make up a very small proportion of grey seal diets and what they do eat tends to be small. The amounts could not explain the increase in mortality among adults. Further work was "urgently needed," they wrote.

At the same time that Shea announced the cod closure, she directed her department "to ensure the targeted removal of grey seals." The problem was, the directive was a little premature: it came before there was any science supporting the hypothesis that the seals were even holding back the recovery.

Critics say that federal scientists were then pushed to justify a cull of seals. In 2011, the Fisheries Resources Conservation Council---a 15-person council with members from both science and industry---recommended killing 140,000 grey seals in five years in the southern Gulf. Six prominent scientists reacted by accusing the government of trying to stack the deck against seals. The scientists---including Boris Worm of Dalhousie University, Sidney Holt, the father of fisheries science and David Lavigne, science advisor to the International Fund for Animal Welfare---sent an open letter to then minister Keith Ashfield saying that after Shea's 2009 directive, some scientists "dutifully set out to provide a rationale for the previously announced cull," that DFO workshops that followed only examined negative impacts of grey seals on cod, not positive ones, and amounted to nothing more than a "self-fulfilling prophecy."

In other words, it came as no surprise that two years after minister Shea announced there would be a cull, the FRCC urged the minister to approve one.

Where the Senate Committee got its numbers

In the autumn, southern Gulf cod migrate great distances from their summer feeding grounds---up to 650 kilometres for some---to the deeper, warmer waters of the Laurentian Channel---a submarine valley that extends from the St. Lawrence estuary to the edge of the continental shelf south of Newfoundland. Here, in the Cabot Strait area, they feed less, use up their energy stores and wait for spring, when they return to the Gulf to spawn. According to information from satellite transmitters attached to some grey seals, it is also here---on the cod overwintering grounds---where the two species overlap and where DFO scientists say big cod are being eaten.

In the winter of 2008, DFO hired sealers to kill grey seals that were foraging around St. Paul's Island---near the overwintering area---to see if they were feeding on the overwintering cod. When the gut contents of the 90 seals were analyzed, scientists were only able to find and reliably measure 33 large cod in 13 of the grey seals. They also noticed that only a few male seals were the cod-feeders while a larger number of seals, many of them female, had eaten hardly any cod. The scientists admitted the sample was "modest" and the evidence "circumstantial," but said that when compared to other hypotheses that were examined---and rejected---including unreported catch, disease, contaminants, poor fish condition and the fact that cod are now maturing and aging prematurely, grey seal predation was still the most likely reason for the cod non-recovery.

This is where the science gets murky. Data were then plugged into models along with a myriad of assumptions---many of them unverifiable---about the way grey seals and cod interact. Different assumptions led to very different conclusions. For instance, one of the models showed that slaughtering all the grey seals would not bring back the southern Gulf cod stock. The results of another model---the source of the Senate Committee recommendation---showed that killing 70 percent of the 104,000 grey seals foraging in the southern Gulf could reverse the cod decline.

Doug Swain is one of the DFO scientists who worked on the cull "scenarios" and he says they should be viewed as "what-if" scenarios and were never meant to be interpreted as a recommendation for a cull. He says there are too many data gaps, particularly about grey seal diets, and so "it is not possible to determine the seal reductions that would be required to allow cod recovery." He points to two key DFO documents---one of which he co-authored---that came to the same conclusion. In fact, in another DFO review of the scientific literature worldwide, it was concluded that there was little evidence that culls actually work and that there was every chance they could backfire.

According to Dal's cod expert, Jeff Hutchings, it is possible that grey seals are contributing to the high natural mortality of cod in the southern Gulf, but, he stresses, "that says nothing about what you do about it." He explains: "This is only happening because of what we did. We're at fault for making cod an endangered species. We're at fault for reducing these populations to levels where they appear to be unable to sustain the natural mortality levels that they're currently experiencing."

David Lavigne of IFAW points to an important glitch in the DFO's rationale---an inconsistency raised by DFO scientists themselves. If grey seals are responsible for the high natural mortality of cod, then why would cod stocks in the vicinity of Sable Island recently be showing signs of recovery---information reported in Nature last year? After all, this is where the bulk of grey seals live and continue to increase in numbers. Lavigne says DFO scientists also can't explain why natural mortality of cod appears similar in the southern Gulf and on the eastern Scotian Shelf despite a four-fold difference in the numbers of grey seals in the two areas. "If adult cod mortality is not directly related to the number of grey seals, then why would a reduction in the numbers of grey seals be expected to reduce adult cod mortality?"

The role of top predators

Most scientists agree that tinkering with an ocean ecosystem to solve one problem could unleash greater havoc and result in any number of unintended consequences. Hutchings says the ecosystem is complex with many species interacting, not just seals and cod, so there's no way to predict the outcome of a cull.

"I don't think any scientist with any integrity would want to make that kind of forecast," he says. "If you remove grey seals, then other things that grey seals consume, like herring and mackerel might increase and they consume cod eggs, and young cod," he says. "You remove one predator [of cod] but you might increase the abundance of two others."

Hutchings points to the common misperception that a predator can only affect its prey negatively---essentially by eating it. But studies show that when you factor in everything else that grey seals eat---including predators of young cod and fish they compete with---they may be having an overall positive impact.

Debbie MacKenzie, head of the Grey Seal Conservation Society, says there's also a growing body of science describing how the swimming and diving behaviours of marine mammals, including grey seals, help to mix ocean water and transport significant amounts of nutrients from the deeper waters to the surface. "This stimulates the growth of plankton, the uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide by the ocean and the production of food and oxygen for many consumers including the grey seal's own prey fish," she says. In this way, large grey seal populations may even counter some of the negative effects of climate change.

"The Senate Committee is recommending that the minister play Russian roulette with the ocean's ecosystem," says Aldworth. She says the greatest threats to cod are all human caused. Overfishing, illegal fishing and destructive fishing gear, as well as pollution and global warming are what ruin fish stocks and their habitat, she says. "While we continue to scapegoat seals for the non-recovery of the cod stocks, we're not focusing attention on the very real factors that are causing non-recovery," she says. "But dealing with those would be costly for the fishing industry and politically difficult for the Canadian government to address."