Shauna Hatt’s best year working in film in Nova Scotia was 2003. It was the SARS and blackout year in Toronto, a city that for years has been the biggest film production centre in North America outside Los Angeles.

American producers, believing the paranoid projections of weak-kneed insurance companies and a plague-ravaged city of mask-wearers, brought their money east to Montreal and Halifax. At the same time, many smaller Canadian productions were green-lit. Business in Atlantic Canada was booming.

“I did Mrs. Ashboro’s Cat over in Charlottetown, and I went from that to Wilby Wonderful and I went straight from Wilby on to Gracie’s Choice,” says Hatt, a production coordinator. “I did a couple of commercials as well, I worked all year, non-stop.

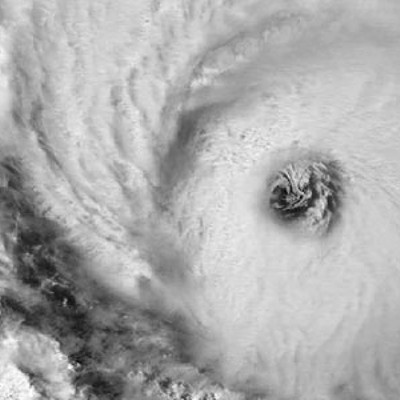

“The way I always remember Gracie’s is that my first day of work was supposed to be the day that Hurricane Juan hit. I was in Toronto and I flew back to be here for the damn hurricane. It occurred to me, ‘Why’d I come home?’ I was safe and sound.”

Hurricane Juan blowing through the Maritimes in September 2003 seemed to foreshadow a downturn in the film business in early 2004, as if Toronto was passing on its force majeures.

“Last year really brought it home when we started to lose films. We had people scouting here, the next thing we knew the shows would be starting up in Winnipeg, and that’s when the panic started. I went from being mildly concerned to deathly afraid.”

The local film business regularly employs over 2,000 Nova Scotians but recently has seen its fortunes drop. Productions from away have gone from a steady stream to a periodic drip, largely due to other provinces sweetening their tax credit deals that allow producers to get money back on labour expenses, provided crew is hired locally.

A strong loonie stems the flow of “runaway production” as well. In an April 16 article in the Los Angeles Times, New Mexico film office director Lisa Strout is quoted as saying, “The higher Canadian dollar has helped us tremendously.” New Mexico, like many other American states, is offering tax credits as well to attract movie production. The new Adam Sandler film, The Longest Yard, was shot there.

But even with an 80-cent dollar, Hollywood can still save money by coming to Canada—just not as much as it did in 2001.The panic in Nova Scotia prompted action. In the fall of 2004, a campaign was launched to get the provincial government to do something, directed by prominent people in the industry. The local actors union, Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists and the film technicians union, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, also came on board. Gilles Belanger, a producer who makes both Canadian- and American-funded movies, was at the forefront of the campaign to raise the tax credit for film productions in Nova Scotia.

“We wanted to enhance what is here and bring more business,” he says. “After Ontario, Manitoba and British Columbia, we had to get moving on our tax credit situation.”

Meetings were held and calls were placed. Suppliers made their case. The unions encouraged their members to write their MLAs, to get active.

Tax credits “are proven to work. It’s revenue neutral,” meaning the expenditure balances out or is less than any potential earning for the province, says Belanger. “It should be a no-brainer. But we still had to fight.”

ACTRA branch representative and chair of the Film Advisory Committee Gary Vermeir says that though the government was responsive in the fall, they wanted to wait until the spring budget came down. “This change had to happen right away because production this year would be affected.”

Shauna Hatt has worked as a production coordinator for eight years. Previously she worked with hotels in event planning. The career change was more of a lateral move as it’s a job that also requires her logistical and organizational skills. She remembers the nascent and quaint film business in the mid-’90s.

“We were housing film crews”—in the hotels—“and I got to know production coordinators. The industry was recruiting people, because they knew they had to get good people in. It was adorable. Back then it wasn’t seen as a valid form of employment.”

Hatt was planning to quit her job and go to university. She did quit, but spent a summer working on a movie, and in her own rapidly retracted words, got stuck.

“Stuck is the wrong word,” she says. “There’s a lot of elements in it that I really enjoy, but it’s one of those things, it’s really hard to get out once you’re in.

“There’s certain personality types that are binge workers, and that’s me. Once I go to work, I may as well work 20 hours, I’m there. I can’t stand the idea of working nine to five.”

Hatt marvels at the way the film industry here has fought to be innovative to make up for what it doesn’t have.

“There’s no way to screen rushes here,” she says. “But on K-19 we built a projection room. And we do it without money, too. We did Wilby Wonderful in Shelburne where you can’t even buy a box of office paper. And you’ve got Sandra Oh flying in from Los Angeles to stay in the dormitory at the abandoned base.”

As a result of the industry campaign, premier John Hamm announced on March 8 that the tax credit would be increased from 30 to 35 percent for productions shot in HRM, and from 35 to 40 percent for rural shoots. In addition, production companies can claim an extra five percent frequent flier bonus if they make two or more films in a two-year period. The credit extension is guaranteed for 10 years.

Less than a day after this announcement, Manitoba increased their credit to 40 percent, 45 for frequent fliers.

“We’re still at a disadvantage,” says Belanger. Manitoba “is closer to LA, but we have mountains and the ocean. I’m happy we’re in a position to compete, but I was hoping for 40 percent.” He adds, “People must realize that a lot of what comes here are not the huge productions that Vancouver gets. We get movie-of-the-weeks that they can’t afford to shoot elsewhere.”

What Belanger is suggesting is the hard truth that Nova Scotia is rarely the first place foreign or even domestic producers will think of to make a movie unless there is a call for the rugged coastline or a “New England” quality. The bigger Canadian cities with generic American looks, conveniences, studio availability and production labs have an undeniable appeal.

In Nova Scotia there are no labs to process the film and produce rushes (footage to be reviewed by the director and producer). At the end of a shooting day, the film is shipped to Toronto for a 24- to 36-hour turnaround, an added cost and concern if locations need to be scrapped or if there’s a technical problem with the footage. Producers who’ve shot in Toronto build relationships with the crews, and knowing they’re reliable is its own kind of currency. It’s not unheard of for producers to want to go back to the big city for other, more intangible reasons, like a favourite performer at a certain gentleman’s club or the al dente penne at an Italian bistro. To compete, Nova Scotia has to bend over backwards.

James Nicholson, a producer for Halifax-based multimedia company Collideascope, says the extra five percent will make the difference, particularly for indigenous productions. Budgets for television shows are often given a go-ahead based on the leanest margins of production costs versus potential revenue, and any credit that can lower costs means more shows will get made. The slightest saving can make all the difference.

“They say, ‘I need for it to cost X,’ and I say ‘if you want so many episodes you can only afford so many days.’ They say, ‘what can we cut?’ until we get to a point where it’s just not worth it” says Nicholson. “So the credit is definitely going to help the situation.”

Gary Vermeir says that the tax credit is only the first step to goose the film and television industry in Atlantic Canada. He wants to lobby the government to change CRTC regulations. In 1999 there were over a dozen dramatic series being shot across Canada, including Emily of New Moon, Lexx and Black Harbour here in the Maritimes. Vermeir says it was the lobbying of private broadcasters who pressured the government to broaden the definition of what is considered Canadian content. Now, cheaply produced reality shows like Canadian Idol, or infotainment like E Talk Daily are under the Cancon umbrella. The production of Canadian television drama took a hit.

Vermeir suggests the onus should be on the private broadcaster to live up to the broadcast act.

“We’ve got to keep the pressure on. We’re not seeing our own stories,” he says. “It’s a matter of culture and jobs and industry.”

Contrary to Vermeir’s position is Ann MacKenzie, CEO of the Nova Scotia Film Development Corporation. She points to recent Atlantic-shot TV productions like Sex Traffic, the two Trudeau miniseries, Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion and even Trailer Park Boys as signs that Canadian drama is still thriving. She’s ecstatic about the tax credit announcement, plus a part of the deal that gives the NSFDC an extra $600,000 to do its work to encourage local filmmaking.

“It’s puts us in a very competitive position. The majority of our production is local filmmakers and they benefit directly. We have fantastic locations—we have a lot more to offer.”

While working the punishing film schedules, Shauna Hatt raised a son, Cody, who is now a teenager. He spends time with his father when Hatt is working.

“He’s had some fabulous experiences because of film,” she says, “like when we’ve been on location and he’s been able to visit.”Hatt is also a recent homeowner. (“Cross your fingers,” she says with a laugh.) With so much uncertainty, major investments like a house can be a serious risk. Though she can pay the bills working on commercials, in this business everything is perishable.

“We walk around going, ‘What if it dries up? What if it dries up?’ you know. I think there’s been that feeling ever since I got into film. It affects you so profoundly if you have a bad year on paper. If you don’t have an employer of record, anytime you’re applying for a loan, or you want to do anything—you’re really not showing a stable income.

“I’m lucky I’m not as specialized as some of the on-set departments. What does someone who has been pulling focus for seven years do if they can’t pay the bills? But people are really good at staving off, at saving their money and making it through the lean times.”

Hatt estimates that in town there are three reliable production crews, which she suggests is a lot for a business that sees maybe six films a year. Despite the struggle, she does remain optimistic after the announcement of the credit change.

“I’m very proud of the way the industry responded to the situation,” she says. “I think this year is going to be better for a lot of people.”