In the early 1990s, Halifax was living the "next Seattle" indie rock legend. Bands like Sloan, Thrush Hermit and jale were influencing kids who would soon embrace the possibility of professional careers in music. The popularity of rock and punk in Halifax made way for Cafe Ole, Condon MacLeod's crammed music club on Barrington Street that rivalled the downtown bars for must-see shows—even though it was a no-alcohol, all-ages venue. So when Cafe Ole closed due to major renovations at neighbouring Neptune Theatre, the thriving all-ages scene needed a new home. Enter The Pavilion.

What started as a swimming pool's storage shed became the centre of the all-ages scene—a vital part of the local music scene, period—until its demise in 2014. Now a group called Bring Back Our Pavilion is raising money to, ummm, bring back The Pavilion. As part of fundraising efforts, this month the venue hosts two shows. The first happens Saturday, which might just mark another another milestone on the venue's twisting road to relevance.

1992 to 1997: Dawn of the all-ages age

Condon MacLeod wanted to provide a safe space for his kids to hang out, so he opened Cafe Ole, with Sloan playing the first show. The alcohol-free club quickly became a place for all kinds of kids, evolving into an important indie music venue, kind of an all-ages equivalent to New York's CBGB. Considered by most youth as the coolest all-ages venue in Halifax, with infrastructure that enabled creators and an atmosphere that encouraged music and the arts in Halifax to flourish, Cafe Ole's model provided the blueprint and the roots of the community for The Pavilion.

Mark Black (musician, author): Before Cafe Ole, putting on a show was work. You'd have to find a hall, convince someone to rent it to you, get equipment, make sure no one destroyed anything and you'd still end up losing money. Hearing about Cafe Ole when you're living in rural communities, your mind was blown. You didn't have to do any of that. It meant kids could concentrate on actually making music, rather than the logistics of playing it.

Meghan Sivani-Merrigan (musician, artist): My first punk show was at Cafe Ole in 1995. I saw this hardcore band called The Chitz. The singer Cara MacDonald was all power and presence. I didn't know women could do that. I wanted to do that. Us younger kids idolized the older ones.

Cara MacDonald (musician, The Chitz): In the Cafe Ole days, there were a lot of women going to shows. But there weren't that many women making music, especially in the punk scene. For me, it was intimidating, because everyone was used to hearing male voices. But more women started to play and Cafe Ole was a welcoming space. We had ideas that it should be open to everybody, regardless of gender, race or class. We really wanted to nurture that, because we wanted everything to grow.

Sivani-Merrigan: There was a large community of people between the ages of 12 and 35, or older. That all-ages scene was extremely important, especially for young girls. I had to see it to believe that I could create art and play in bands.

MacDonald: If you lived in Dartmouth, Sackville, Bedford, you'd only see people at those shows. They were your friends that you didn't go to school with. They were your people, sometimes life-long friends. Cafe Ole established a community that would grow into The Pavilion.

Sivani-Merrigan: In 1997, Cafe Ole was forced to close by Neptune Theatre, due to their renovations, despite our protests and campaigns.

MacDonald: Everybody felt very lost without Cafe Ole, because it was hard to find space for shows, especially all-ages shows. Condon was very pressured to keep that going. People's parents were writing letters and stuff.

Condon MacLeod (owner, Cafe Ole; manager, The Pavilion, 1998 to 2003): Shortly after Cafe Ole closed, one of the city councillors said people had expressed the need for an all-ages venue again. There was a building on the Central Common available, so we checked it out and said, this is great. There were papers signed, a contract of sorts. Just as long as we made enough money to support it. Any money leftover went to the bands.

1998 to 2003: The Pavilion, a glorified utility shed

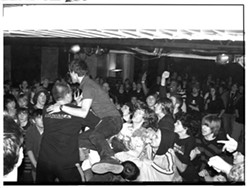

The Pavilion opened in 1998, in a non-descript storage shed near two high schools. Funded by the city, MacLeod would spend hours at the venue scheduling local bands, doing promotion and supporting a scene that would flourish. There was nothing fancy about The Pavilion, but that's what people liked. It belonged to the community.

Waye Mason (former coordinator, Halifax Pop Explosion, current city councillor): Condon had a good thing going at Cafe Ole, but The Pavilion was different, a little bigger and more bare-bones at first.

Sean MacGillivray (sound tech, 1998 to 2003): No one else was really using the space. The basement was storage. It was a utility building, a glorified shed.

Black: The stage was two-by-fours with pieces of plywood on them. It wasn't high, but it didn't need to be. It just needed to be a platform. Simple lighting. The sound system was rented from Buckley's or whatever. It wasn't anything great, but no one cared, we just wanted a place to play. Condon ran it hand-in-hand with the city. He was very good at letting kids have their say and including as many kids as possible.

MacDonald: When The Pavilion opened, it was like, "Yes! We're getting this thing back that we love and cherish so much." But the community changed between Cafe Ole and The Pavilion, just because a year is a long time when you're 17. Some people became legal drinking age and went to bars instead.

Ian Hart (guitarist, Risky Business): I think generally the whole scene moved from Cafe Ole to The Pavilion.

MacDonald: It turned out I didn't really like The Pavilion. Cafe Ole was downtown, dirty, grimy and dark. The Pavilion was a white government-owned cinderblock building. But that was part of me being so attached to Cafe Ole, and I was getting older.

Nathan Doucet (musician; Pavilion manager, 2003 to 2005): Coming out of Cafe Ole, there was a huge transition, but The Pavilion was centred around the same ideas. We considered ourselves feminists. Some of us were involved in Food Not Bombs and organizations like that. But Condon never got too political, to keep the space accessible and inclusive. People volunteered because there were cool jobs to do, running the canteen, the sound booth or doors.

MacLeod: Anytime you'd tell people that you're working with young people, they'd always ask what problems you'd be having. We didn't have any. The place looked after itself. It was self-policing. Most kids were socially conscious. If someone was acting up, they'd say, hey, that's not cool. Don't do that here.

Doucet: There was a bunch of willing participants because it made you feel like you were a part of it. At that time, people were listening to hardcore and were into the ethics of it, so it was like, "This is a community, this is our place that we take care of." It was a place for people to express themselves. Condon facilitated that mentality pretty heavily, and it worked because he cared about everybody, and cared about the place a lot.

MacLeod: It was a labour of love. We didn't realize at the time the importance of it.

Black: Condon would have different kinds of shows. There'd be a rap show, then punk, then a rave or hip-hop. Every weekend had a new lineup. It catered to a bunch of different communities.

MacLeod: We had Joel Plaskett in there, Skratch Bastid, Classified, Rich Terfry. It wasn't always what I'd listen to at home, but what I enjoyed so much was getting caught up in the energy and enthusiasm. It was about seeing all the genres do an amazing job. It was an opportunity for kids to perform in a club atmosphere in front of their peers.

Black: Everyone co-existed. There were really diverse groups using the space regularly. Everyone was coming from Porters Lake or Hubbards or Tantallon, and you'd converge on weekends there. That's where you formed bands, met friends, handed out your zine. That's where you did your shit.

Haley Mombourquette (musician): I grew up in St. Margarets Bay, sheltered from the city scene until I was 15. I joined The Kworms in '99 and we'd play The Pavilion at least once a month. It was the only place we could play, and we would pack the joint. Good exposure, terrible sound.

MacGillivray: Shows at The Pavilion could be really tame, or totally wild.

Hart: One of the best things about it was that you could make noise there 24/7.

Mombourquette: It was home. It was stinky and loud as fuck. I had my heart broken there, started new relationships, the full emotional range of teenage bullshit. It was important to me. Otherwise, I was very alone, the only chick in my high school playing metal and totally disappointing my dad.

MacLeod: I had recipe cards with the bands that would play with their ages, what instruments, what type of music. I still have them. There were at least 1,200 bands that performed in that time. Everybody got a chance. The scene was really healthy and there was so much going on.

Sivani-Merrigan: There was a strong anti-racist component to the scene, too, which benefited me as an often-confused biracial kid. I was desperate for a sense of belonging. Musically, I was able to perform in a professional setting at the age of 15. Nothing teaches a musician quicker than performing live.

2003 to 2014: Growing pains

In 2003, the city required The Pavilion to shut down for renovations, mostly electrical and fire-code related, and MacLeod gave up his post. The Pavilion reopened in August 2004 with a concert by Joel Plaskett, under the new management of local promoter Chris Smith. Over the next decade, The Pavilion shifted away from its DIY origins.

Chris Smith (promoter, manager 2004 to 2014): I had booked a few shows with Condon just before The Pavilion closed and it was good times. As a promoter, I knew that it was important for younger fans to see shows because they'd eventually go to bar shows. I saw a request for proposals to run an all-ages music venue there, so I put together projections, a proposal for programming and how we'd operate. I gave a presentation and the recreation committee offered me a partnership with HRM to run a dedicated youth space, specifically for music, secondarily for arts.

Mason: When Chris relaunched, it was constantly upgraded and painted. The couches, stage and sound booth all improved.

Doucet: It was a whole new world. But it became a lot more corporate.

Smith: Yes, I ran it as a business from 2004 to 2010. We had to cover insurance; I had to get sponsors. I was apprehensive about sponsorship, but Aliant stepped up and was a great partner. They didn't force any corporate messages on the kids, but we did have a couple computer kiosks for kids to check their Hotmail, which was cool.

Black: It did become much more like a business, with less of a homegrown scene. It just felt different. And as some of us got older, it became someone else's Pavilion.

Hart: Risky Business played our last show there in 2007. I think what was missing from early days was getting new local bands to play, and fostering a new crop of kids coming in.

Adrian Bruhm (sound tech, 2005 to 2008): It was great for touring bands who could make a little cash to make the trip here worthwhile.

Doucet: I think The Pavilion changed because music changed. By the late 2000s, there would be 300 kids with straightened black hair who loved screamo and emo. It had moved from the DIY-ethics of the Condon days, but it still represented a community for me, and I had friends there. But it was different in ways.

Bruhm: There were a lot of really big shows happening like Treble Charger, The Weakerthans, Bif Naked, Sum 41. Way more.

Black: A Sight for Sewn Eyes played a lot. There were Battle of the Bands, where six bands would play and one would win a $200 cash prize. But I always thought, shouldn't everyone get paid? I'm not sure everyone was always getting paid, and that was different from Condon. It was just like, where was the money going?

Mason: I booked shows there for Halifax Pop Explosion and we used substantial sponsor money to put bigger bands in the Pavilion than it could really afford, with mixed results.

Hart: I remember a bunch of punks got in a fight with Serial Joe because they had a tour bus outside. It pissed punks off that a band their age would have a tour bus.

Doucet: There was some violence. One cool guy did security. Security Steve. But even he got the shit kicked out of him one bad night. For a while, you had 300 kids with me as the adult, and of course some kids were drunk, or selling or buying drugs on the Common. There were swarmings at the time and the cops weren't that responsive to the space. We had to start requesting bike police. But that's just regular teenage stuff. I don't think it lasted too long.

Smith: After a couple years, turnouts were low. I think show-going and music scenes in general are cyclical. By 2009 it was getting apparent I couldn't run The Pavilion as a for-profit business. In 2010, the city agreed we could switch to a not-for-profit with a board, which became The Pavilion Youth Association. By 2014, there was some downward pressure on city budgets and ours got readjusted and our agreement ended.

2015 to now: The comeback trail

In the wake of The Pavilion's 2014 closing as a full-time venue, The Pavilion Youth Association and the city have been in discussions about how to revitalize it. Last fall, while giving a lecture in the NSCC's Music Business program, Smith inspired a group of NSCC students to form Bring Back Our Pavilion, which has been dedicated to raising the $7,000 the city recommends as a minimum operating budget. This Saturday's show at The Pavilion is an example of BBOP's efforts. In the meantime, The Pavilion is available to rent from HRM, and has been used by cultural groups like Youth Art Connection.

C.J. Hill (musician, student): I run The Pavilion Student Committee, which runs BBOP, about 15 students who are passionate about giving youth the opportunity to see live music. I'm originally from the Valley and would travel to Halifax to see shows at The Pavilion. Youths deserve the same opportunities to see live music as I did. We're fundraising to cover costs and so far we've raised over $1,300.

Black: Obviously, there's money to be made, but The Pavilion should be an arts incubator. Not a "for-profit" thing. It should be a place for kids to perform, run by adults.

Bruhm: It will never make money long-term, but it will inspire people to do important things. Kids who went to there went on to follow their dreams. Look at $Rockin 4 Dollar$, Hitman, Black Moor, Nap Eyes, Monomyth, Each Other, Hand Cream. So many.

Smith: What I found rewarding—when it wasn't profitable or when I was putting money back into it—was seeing young adults come through the door, knowing you had a hand in watching them become who they are. I think city staff and councillor Mason understand there's a need for it, and they've been supporting us. We just have to organize it all. It was hard for some of the city to understand the venue and what The Pavilion was doing. It's a specialized skill-set to develop all-ages music programming. I'd like to see a full-time manager there.

Mason: If you want a good music scene, you need to encourage teens by having a place to play and watch music. The Pavilion's absence over the last three years is felt in the scene.

Smith: The Pavilion is unique. There aren't a lot of places like it. Touring bands would often say they wished they had a Pavilion. It's for youth with similar interests who might be overlooked in other recreational programs. It's not just a music venue, it's a community forum.

Hill: It has a history tied to youth music in the city. There is certainly enough interest from youth to keep it going. With the right group of people behind it, we can establish a live music scene for youth for years to come.

Adria Young is the staff writer at The Coast. Her favourite Pavilion show was the collaboration between Moon, Dirty Beaches, Heaven for Real and Diana at HPX 2013.

Pavilion Fundraiser Show w/A Sight For Sewn Eyes, Sleepshaker, Of Vice & Virtue, Background Noise

Saturday, May 14, 6:30pm

The Pavilion, 5816 Cogswell Street

$10 advance/$15 door