In Fort Needham Memorial Park in north end Halifax, Noel Taussig's ears perk at the staccato tweet of what he thinks might be a magnolia warbler, a gorgeous little yellow-breasted bird. "Weep, weep, weep, eeeep! Eep-eep-eep-eep-eep." We tread lightly to the patch of trees where the sound originates and hear it again, this time behind us, right where we started from. We backtrack until he can point it out to me. It turns out to be a song sparrow.

Taussig is not an ornithologist by training. He's just learning how to identify birds by their size, colour, patterns, sounds and how they flap their wings. Not long ago he was a carpenter, until he hurt his back. Now he works at the Ecology Action Centre, exploiting the celebrity of the Hali-famous to get layfolk pumped about birds and interested in ending the current plummet in their population. It's part of EAC's Birds Are Back Celebrity Bird-watch Challenge.

Most newbie participants in the celebrity challenge were reluctant, clueless as to the purpose of the exercise. In other words, normal city-folk. But that changed. "For a city girl who hates anything to do with outside and nature," says Joanne Bernard, director of Alice House, "I really enjoyed this...I even bought a couple of birdfeeders."

For the record, Costas Halavrezos of CBC's Maritime Noon fame was the most ineffectual birder of the bunch. "I know there are loons in Lake Micmac," he says, "but perversely, they've stayed out of sight."

As much as the Hali-famous now love them, Taussig's work is not just for the birds. "They are an indicator of the health of all ecosystems, including aquatic ecosystems." Thanks to human use of pesticides, destruction of forests and light pollution, the total bird population in North America has been cut in half in just four decades.

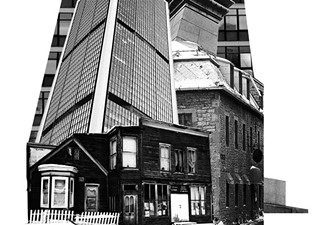

If that's an indication of the health of the environment on this continent, we're in as much trouble as the birds are. Cities have become the worst habitat for most birds---Toronto labourers sweep away hundreds of carcasses a day, usually victims of tall buildings covered in reflective glass. They confuse the hell out of birds, creating a nightmarish maze of their own reflections. Tall buildings are less of a problem in Halifax, but new development rules under HRM by Design may change that.

Only a few species do well in cities. Most bird watchers aspire to escape the city every chance they get, but in Halifax there are a few prime locations, like Frog Pond off Purcells Cove Road, Sullivan's Pond in Dartmouth and Point Pleasant Park.

For the hardcore, Halifax's crows, starlings, sparrows and rock doves (sort of a euphemism for what some call winged rats, or just pigeons) are nothing to stay home about. Occasionally, the urban birder may luck out and see one of our larger birds of prey: an osprey, a (duck-eating) eagle, even a peregrine falcon, the world's fastest animal. "Falcons are just recovering from DDT," Taussig says, adding that urban pesticide use is perhaps the biggest bird killer of all, and thus a major ecosystem killer. He has yet to see a peregrine in Halifax, but says they actually thrive on steep surfaces like cliffs. Or downtown buildings.

"For me, Halifax birds are still exciting because it's all new to me," Taussig adds, but he feels himself falling deeper into the strangeness of birding culture. "I'm slowly becoming one of them; every time I step outside I'm looking up and listening."

It shows. Despite his newbie status, Taussig can passionately recite inspiring bird facts, ways in which we are attuned to our feathered friends. "We think of them as timid and frightened, but birds are very curious," he says. "That's why birders will make a strange psh psh psh sound. If you do that, the birds come to you to see what the heck the noise is." In his short birding career, he has noticed that starlings will mimic car alarms, and that higher perching birds tend to make higher pitched calls. Also, he says, most birds are monogamous.

Taussig is already planning for his next foray into raising bird awareness: taking daycare and grade-school classes on birding expeditions. He is confident the kids will quickly fall in love with birding. "Everyone who gives it a real try loves it," Taussig says. "Birds poke us in just the right spot. As kids I think we all dreamed about being able to fly."

What do you see when you're watching like a hawk?Let me know: [email protected].