The urgent and vivid public discourse surrounding rape culture has perhaps never been so ubiquitous. The stampede of coverage in the wake of a (seemingly nonstop) list of allegations of sexual misconduct against powerful men in media, entertainment and government is not slowing down—if anything it seems to be gaining more traction all the time.

As more survivors come forward, renewed calls for action follow in quick succession.

All the while, a Halifax lawyer has been quietly and carefully documenting the Canadian justice system’s handling of sexual assault cases. The result of Elaine Craig’s sweeping investigation is being printed right now. Her book, Putting Trials on Trial: Sexual Assault and the Failure of the Legal Profession, is slated for release in early 2018.

“We seem to be in a moment,” Craig says, pointing to “unprecedented consideration of sexual assault and sexual harassment, and the legal system’s response to it.”

The associate professor at Dalhousie’s Schulich School of Law began research for her book back in 2010. This was long before the Harvey Weinstein and Louis C. K. bombshells from the New York Times confirmed what had been whispered about for years. It was before the allegations of sexual harassment against Al Franken, Charlie Rose, Dustin Hoffman, Kevin Spacey, Mark Halperin, Roy Moore, Glenn Thrush and dozens more came out over the past month. This was years before the Ghomeshi trial—years before Canadian judges were telling victims of sexual assault they should “keep your knees together” or that “clearly, a drunk can consent.”

Public scrutiny in Canada seems to have leapt forward when it comes to rape culture and issues surrounding the justice system. People are finally, mercifully, paying attention. That doesn’t mean anything much has changed.

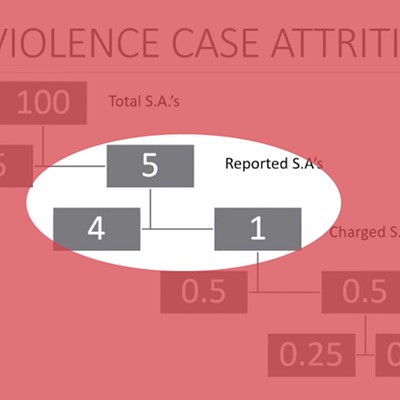

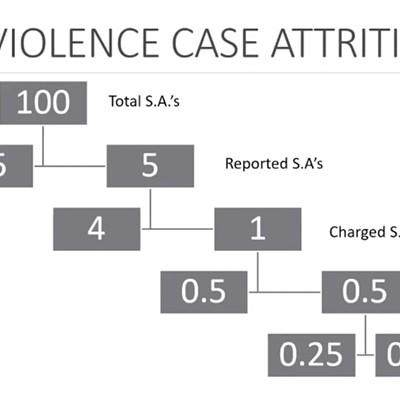

The number of sexual assault cases deemed by police as “unfounded” remain mammoth, as the Globe and Mail

“Reporting rates have not increased,” Craig says. “Conviction rates have stayed the same. Survivors continue to experience the criminal justice system as traumatic.”

For years, feminists in the justice system and academia have been trying to draw attention to this inconsistency. Canada’s rape shield laws are held up internationally as the most rigorous, most robust provisions on the books. But the gold-standard system isn’t producing results.

“How can we have such powerful law reform, the most progressive changes in the world to the law of sexual assault and have it not impact on the ground in any real way?” Craig asks.

Her research on that question examines specific trials across Canada. Craig spent hours documenting and re-reading trial transcripts—in some cases, listening to the actual voices of complainants, witnesses and judges in the courtroom via audio transcripts.

Her writing provides concrete examples of systemic injustices. Her findings spare no one across the legal and justice professions.

“[There are] problematic attitudes and stereotypical thinking on the part of

Craig has developed something of an

But as Craig’s book shows—through interviews with lawyers that hint at a common narrative amongst the criminal defence bar—whacking the complainant isn’t some antiquated technique of the past.

“There’s a disconnect there,” Craig explains, “[because] empirical evidence suggests that women continue to experience the trial process as deeply traumatic.”

But before such an issue can be addressed, it must be acknowledged.

“You’ve gotta convince the legal profession that this problem even exists.”

Canada’s justice system has a long way to go, and Craig says she doesn’t know how her academic research will be received. But she does know one thing for certain.

“This book is going to generate controversy.”

About time.