If they were brave enough to push back—to negotiate a little—they were met with, “in Nova Scotia there's no rent control right?” And that was it.

It's not like they’d just repainted the hallways, or finally found the perfect shelf to fit in that weird nook behind the top of the stairs. They’d taken a risk to move out on their own, laid out a budget, picked up an extra shift and said: “I can make this work.”

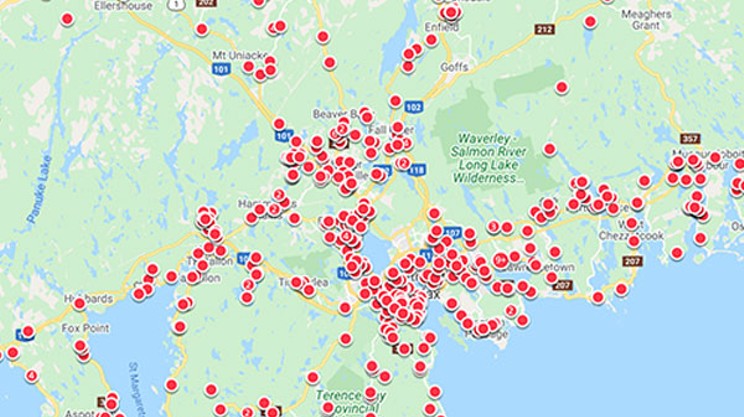

The consequence of supply not keeping up with demand caught up with them. They were shit out of luck in a city with a dangerously low vacancy rate, out-dated rental standards, the creeping spread of unregulated Airbnb ghost hotels, a policy kerfuffle of responsibility between municipal and provincial governments, and population growth that showed no sign of slowing down anytime soon.

All of these people were having a bad time renting before the pandemic, and the Nova Scotia Liberals' about-face on rent control comes a little too late for every single one of them.

Yesterday, the province announced that until the end of the state of emergency (or until February 2022, whichever comes first), rents in Nova Scotia can’t increase by more than two percent each year. Official renovictions aren’t allowed—though we know many do and will happen unofficially—and this cap is being applied retroactively, meaning anyone who got a rent increase for September 1, October 1, or November 1 can ask for a credit for increases paid over that two percent cap.

This is huge. But should we celebrate that it took a pandemic for politicians—the majority of whom own their homes and haven’t rented in years—to wake up to Halifax’s housing crisis?

When early Covid frenzy meant toilet paper droughts and plastic cylinders of Lysol wipes going for $30 a pop, the provincial government’s state of emergency brought in protections against price gouging. Price gouging is what happens when the people who control access to a commodity notice that demand is higher than supply, and then use that as an excuse to jack up the price and call it “market fluctuation”.

What actually fell under the umbrella of price gouging protection was fairly vague, but Halifax Magazine summed it up nicely on April 3, saying, “If you don’t need that product to live safely right now, it probably isn’t.”

The Coast stands humbly here today to argue that the place in which you’re doing the living is requisite to your ability to live safely, and as such, price gouging on rents is probably worth prohibiting.

Because the pandemic has brought even more meaning to the safety of staying home, it makes sense that the provincial government is using the state of emergency to reason with landlords as to why there should be government controls on the increases in rent prices. And it’s a good thing. A cap on rent increases will truly change people’s lives.

But Coast readers have been telling us for years—not just since the pandemic started—that renting is a relentless struggle. Take The Coast’s 2019 rental housing survey: of over 500 respondents, 41 percent told us they were paying more than they’d budgeted for their rent. Of the total, 62 percent of them weren’t earning enough to have the city's average rent cost qualify as official “affordable housing,” which Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation says is paying less than one third of your income on housing.

A cap of two percent means someone who was looking at a 33 percent increase on their $1,200 rent will now only have to worry about an extra $244 a year, versus $4,800.

And that matters, because while the average price of a two-bedroom apartment in Halifax has increased 43 percent in the last five years, minimum wage has only gone up 15 percent.

In 2015, you were making $22,048 a year if you were making minimum wage, and if you shared the average two-bedroom apartment with a friend, you were spending 29 percent of your income on housing. Which is to say, things were pretty good. Remember, the CMHC definition of affordable housing is spending no more than one-third of your income on housing.

In 2020, you’re making $26,104 a year if you're earning minimum wage. Sharing the average two-bedroom apartment with a friend will run you $931 a month—which is 43 percent of your income. (If you're a single person on income assistance with no dependents, you’re $345 short for rent alone with zero money left over for anything else.)

The discrepancy has led to a city where some people become unhoused (the number of people in HRM who are homeless doubled in the last year), some people have left the city (“I moved out of Halifax this summer,” Jonah Cole told the Coast, “a decision influenced partially by the increasing cost of rent”) and some people are living in shitty places, staying with abusive partners, or are just living beyond their means.

A proposed rental registry is supposed to give HRM an understanding of how many units are actually for rent in this city, guide enforcement of rental standards, and help tenants to avoid bad landlords. (The last part only works if there are landlords to spare, which isn’t the case when the 2019 vacancy rate was at just one percent).

There are proposed restrictions for Airbnb which would wipe out ghost hotels and work to keep housing stock for long-term rentals. (By contrast, Tourism Nova Scotia just partnered with Airbnb and who is paying for sponsored posts on social media about the initiative as we speak).

Just this week, council divvied up $8.65 million from the federal government for 28 new non-profit affordable housing units. (HRM currently has only about 1,250 of these units—a number which hasn’t changed much in the last decade.)

And it's promised to move faster to approve new construction on units, which is meant to help increase the supply.

All of these efforts have attempted to dull the crisis, but couldn’t touch the real problem: That the price of renting was rising faster than the wages people were earning, and people couldn’t afford to live in this city.

Putting a two-percent cap on the increase of rent—a number that comes in between Ontario’s 2.2 percent and PEI’s 1.3 percent—gives minimum wage a chance to catch up and Halifax renters a chance to look around and say, 'hey, this place could really be my home for the next few years’.

It had Coast readers saying things like “So many less people will become homeless this winter,” and “I’m not going to live in fear that I randomly won’t be able to afford my apartment!” Or “January rent increase went from 13.6 percent to 2 percent.. fantastic news!”

“More security knowing the landlord won’t jack up the rent suddenly.”

“I might actually find a 1 bedroom that my partner and I can afford.”

“So much relief and feelings of security! I don’t have to be anxious about moving this year.”

“I don’t have to worry about my rent increasing out of my budget this spring and def won’t have to move.” And this:

“It will save my elderly father from having to find a cheaper place to live.”

Not often does a new policy actually merit a flood of positive answers to the question “How will this announcement change your life?” Here’s hoping it sticks.

Correction: This article originally stated that Tourism Nova Scotia is paying for the sponsored posts with Airbnb. That is incorrect. Airbnb is financing the campaign. The Coast regrets the error.